BRANDEE EASTER

ENGLISH 142: MYSTERY AND CRIME FITION ONLINE

Summer 2017 and 2018 (8 week format); Adapted from Professor Caroline Levine

Course Description for Students

Imagine that you come upon a dead body. How do you figure out how it got there? What if there are no eyewitnesses? What if witnesses are lying? What if the evidence has been tainted or planted? Maybe someone is acting oddly, or has a strong motive. Do you leap to conclude that that person is the killer? If you make a mistake, a killer could go free and an innocent person be jailed for life. How do you know for sure that you have arrived at the truth?

Just like the detectives you’ve seen on TV, you’re going to run into lots of questions in your own life that can’t be answered by just asking an expert or by searching for answers on Google. In this class we’ll think about how and why popular culture became obsessed with the pursuit of knowledge. We’ll think about how fictional detectives model the work of distinguishing truth from lies. They’ll introduce us to a whole range of strategies for finding knowledge, from ballistics to psychological analysis and from teamwork to guesswork. We’ll think about who gets to pursue knowledge, and how they do it. And we’ll read about historians, philosophers, and scientists who have taken the fictional detective as their model for gathering knowledge and think about how in the University we all need to act like detectives.

Course Format Description for Students

This course is conducted entirely online through Canvas. All work can be completed asynchronously, and you never need to be available at a certain time. All due dates are designed to be completed flexibly with your schedule, and you should plan ahead when necessary to meet them all. However, this course cannot be completed early, so you should be available all eight weeks of the term. For more on due dates, look to our course schedule below.

The Instructor’s Reflection on Writing in English 142

One of the main challenges—perhaps the main challenge—of adapting English 142 (a large lecture literature course enrolling 160 students) into an online format was figuring out what to do about the writing. Because it was taught entirely through D2L and then Canvas, writing’s centrality to the course was inevitable, and this brought both possibilities and constraints. At first, the amount of writing that was required to meet the course goals seemed like a struggle. Course goals that are usually accomplished through in-person discussion, conferencing, or collaborating instead needed to be developed through writing, and this demand on both TA and student labor adds up quickly. Instead of being frustrated, I approached the course’s writing as an opportunity for reflection, analysis, and skill building throughout parts of the course that normally wouldn’t have had the benefits of writing, while still being mindful about writing’s challenges for instructors and students.

There are three main writing components to this course: two 4-5 page essays, weekly writing assignments, and weekly discussion posts. (The course also included weekly reading quizzes and video lectures.) I’ve also included assignment goals, assessment criteria, and rubrics, which were incredibly important for communicating across the platform, the courses, syllabus and schedule, and some miscellaneous tips learned.

Other Tips from Instructor Brandee Easter:

Tips about the labor of writing

The increase of writing in this class meant an increase in TA and student labor, and this raised big questions about how to provide an equitable experience to English 142’s offline version if it involves such an increase in writing. Here are some strategies and approaches used to help manage this:

• Canvas rubrics: To cut TA labor, we used Canvas’s rubrics, which are built in for quick grading. Using this system, Canvas will calculate the points allowing the grader to only need to click on the boxes the assignment is fulfilling

• Conferences: Requiring brief one-on-one conferences twice through the semester provided the opportunity for verbal, instead of written, feedback and guidance.

• Less is more: Weekly writing assignments were built to take no longer than 30 minutes, and each one was focused on a particular skill, which allowed most assignments to be a paragraph or even a few sentences.

• Preparing students early: Because the class was 8 weeks, students were asked to begin thinking about major essays very early. Writing assignments were shorter or eliminated on weeks longer papers were due.

Tips for communicating clearly

I found that communicating expectations and goals for the course and its writing were amplified by the online format, and these are a few strategies that helped me to be clear in setting expectations, providing feedback, and helping students feel in control of their writing.

• Consistent schedule and assignments. Every week, including writing assignments and due dates, were structured the same way. The calendar in the syllabus (on page 18) was important for setting these expectations and being clear about how much time the course is expected to take.

• Consistent feedback. Grades scheduled to return regularly each week. Both instructors and students needed to follow deadlines.

• Include goals, rubrics, and examples with the prompt.

Sample Discussion Posts

Discussion was formatted in 3 parts, due Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday of each week, that asked them to respond to a prompt as well as each other. Students were divided into groups of about 5 for these.

Format

Part 1: Answer the week’s prompt in 150-250 words, including one direct quote from the readings to support your idea. This post should be entirely independent from any other and should think beyond repeating material from lecture. Due: 11:59PM Wednesday

Part 2: Once everyone in your group has written an initial post on Wednesday, respond to at least one of your classmate’s ideas by asking questions, adding evidence, strengthening arguments, or pushing back. This response should be 100-200 words. Due: 11:59PM Thursday

Part 3: Return to your own post and consider the questions and feedback from your classmates. Compose a final 100-200 word response that engages with their ideas, such as by expanding or revising your original idea. Due: 11:59PM Friday

**We included these instructions with every week’s prompt so that expectations were clear**

WEEK 5

Both The Wire and The Private Eye significantly revise the detective fiction genre. They are unlike many of the texts we’ve studied so far in this class. For your discussion posts this week, you’ll need to reflect on one particular way that The Wire or The Private Eye does not fit with the conventions of detective fiction.

In part one (due Wednesday at 11:59PM), you’ll need to:

(1) Identify a convention of the detective fiction genre. In order to answer this question, you can think about the protagonist, antagonist, other characters, imagery, temporal frame, setting, themes, plot, point of view, tone, etc. of the detective fiction that we’ve read so far.

(2) Note at least one text that we’ve read or watched in previous weeks (this means works other than The Wire or The Private Eye) that includes this convention.

(3) Explain how The Wire or The Private Eye revises or changes this convention. In order to illustrate your claim, cite a particular scene from one of these texts.

(4) Finally, explain the “so what.” Answer this question: Why did the author(s) of The Wire or The Private Eye decide to make this change?

In answering these questions, do not repeat ideas that lecture has already covered. When answering question four, your answer should relate to the meaning of the text. Try to figure out what kind of argument the text is trying to make about detective fiction itself or some other theme. Avoid answers that claim that the authors made a certain choice so that the text would be more enjoyable, exciting, or that there is some practical reason for the change, since these answers do not relate to meaning.

Part Two (due Thursday at 11:59PM): Respond to someone else’s post. You can either ask a clarifying question to further unpack their reading, provide more evidence for their reading OR provide (and close read) counter-evidence to challenge their reading.

Part Three (due Friday at 11:59PM): Your third post should respond to someone’s response to your original post.

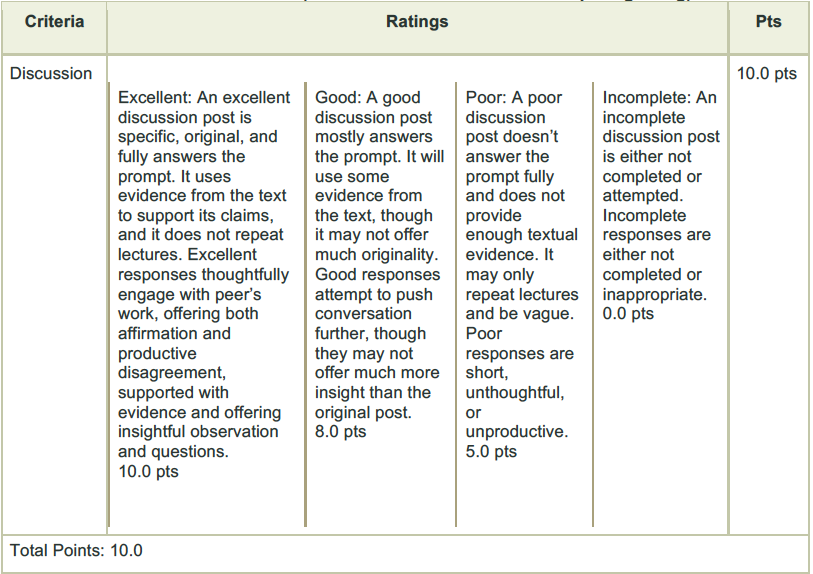

Discussion Rubric (built in Canvas and clickable for quick grading)

Sample Weekly Writing Assignments

Because face-to-face instructional time for writing skills, which are often part of lectures or sections were lost, I developed short writing instructional videos (about 5-7 minutes) and weekly writing assignments for practicing those skills. These assignments asked students to practice prewriting, planning, evidence gathering, and analysis toward their specific chosen essay prompt. It was also important that these were also graded pass/fail because the point was to provide the opportunity low-stakes practice, feedback, and preparation for the longer essay. These also served as an important check-in for instructors, and TAs and I adjusted these weekly assignments each week in response to student needs. For example, one week’s assignment to begin drafting a thesis statement revealed that many were not yet developing an argument-driven statement, so the following week’s assignment was built to specifically address this need.

Weeks 5-6 (building toward Final Paper)

WEEK 5: Prewriting

This week’s writing assignment asks you to brainstorm and begin working toward the claims you’ll make in your final paper. Review the final paper prompt options and think about which ones might be the most interesting to you.

Then, choose two of the three prompts and write short answers to the following, for each.

1. What about this prompt is interesting to you? Why might you choose this one for your paper?

2. Which books, articles, television, etc from the class would you use for evidence?

3. Referring back to Week 2’s writing assignment on making claims, draft a possible thesis statement.

You should submit these answers for two possible prompts by Friday at 11:59PM.

WEEK 6: Outline

Using feedback from your TAs on last week’s thesis statements, choose which claim you would like to develop in your paper. Then, use this week’s writing assignment to help you plan and organize your argument. Here is a short video explaining the MEAL plan: ______.

The MEAL plan is a tool for organizing the body paragraphs of argument-driven papers. The acronym stands for the parts that every body paragraph needs to have. (Note that this structure does not apply to your introduction or conclusion.)

M – Main Idea – The claim being made in the paragraph, or the topic sentence.

E – Evidence – The research, data, quotes, etc that prove your main idea. For a literary analysis paper, this means the evidence from the text, including quotes as well as paraphrasing of scenes or moments, that support your claim.

A – Analysis – The explanation for how evidence you’ve presented proves what you think it proves. **This is the most important part of a paragraph. You should spend just as long, if not twice as long, on analysis as you do evidence.**

L – Link – A transition that either connects back to the thesis or to the next paragraph’s main idea

For this assignment, create an outline of your paper testing out this format for your body paragraphs. The goal is to give you a roadmap and give your TA the ability to give you good feedback before drafting.

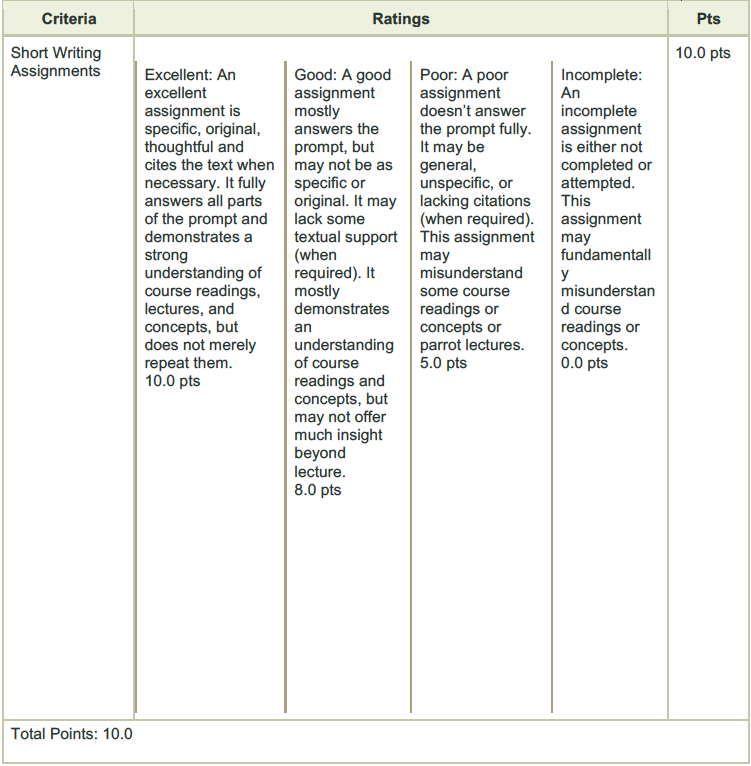

Short Writing Assignments Rubric (built and clickable in Canvas for quick grading)

Final Paper

Length: 4-5 pages

Due: Friday, August 11, 11:59PM CT

This semester, we have thought about how the genre of detective fiction changes over time. Authors have drawn upon previous stories, plots, and conventions, but they have also introduced new elements. We’ve also talked about how detective fiction is reflective of the culture that produced it. In this essay, choose one of the following concepts and explore it through at least three detectives (in three different texts) and four exact quotations, investigating how this concept works and changes in the genre, being mindful to push your thinking beyond what is discussed in lecture. In other words, this paper should be more than scissors-and-paste thinking from lecture. It should involve you asking and answering your own questions.

**The weekly writing assignments will help you complete this assignment and are designed as steps toward the paper. Pay attention to your TA’s feedback each week for help developing this paper.**

#1 STRUCTURES OF POWER: The detectives we have studied this semester operate within widely differing structures of power (nations, governments, bureaucracies, race, gender, social relations and stratifications, etc). Choose three texts from the course and explain how the power structures surrounding the detective affect the ways in which those detectives gain knowledge and access truth.

#2 TRUTH: We have explored the ways and types of knowledge detective fiction can help us access, but we have also considered the limits of the genre to help us know. Choose three texts from the course and make an argument about this strange paradox of detective fiction. Can detective fiction help us find knowledge and truth? In what ways? Where does it succeed and where does it fail?

#3 EMOTION: Detective fiction has often debated the value of emotion and feeling in the process of knowledge gathering. Some have excluded emotion from detection, while others have suggested that emotion is a crucial part of knowledge. Make an argument either for or against emotion as a valuable part of the process of gaining knowledge and determining the truth, using three of the texts we have read this semester to support your argument.

Requirements

Your paper must have the following

– 4-5 pages in 12pt Times New Roman, double-spaced

– At least four exact quotations from three different detectives (in three different texts)

Goals

– Show your firm and precise understanding of the course

– Think deeply about course concepts and themes and push beyond lecture

Grading Rubric

– Argument and Persuasiveness (40%): This paper presents a focused argument, stated clearly in a thesis statement. Every claim in the paper should be supported by convincing textual evidence. Each piece of evidence should be thoroughly analyzed and explained.

– Comprehension and Application of Course Material (40%): Paper should demonstrate an understanding and engagement with the course readings, especially by pushing ideas beyond those covered in lecture. Paper shows original thinking and application of the course material.

– Clarity, Organization, and Presentation (20%): Paper should contain a thesis, and each paragraph should address one main idea. Paragraphs should logically connect to each other. Paper should be correctly formatted and proofread. All quotes are properly cited.