By Matthew Fledderjohann –

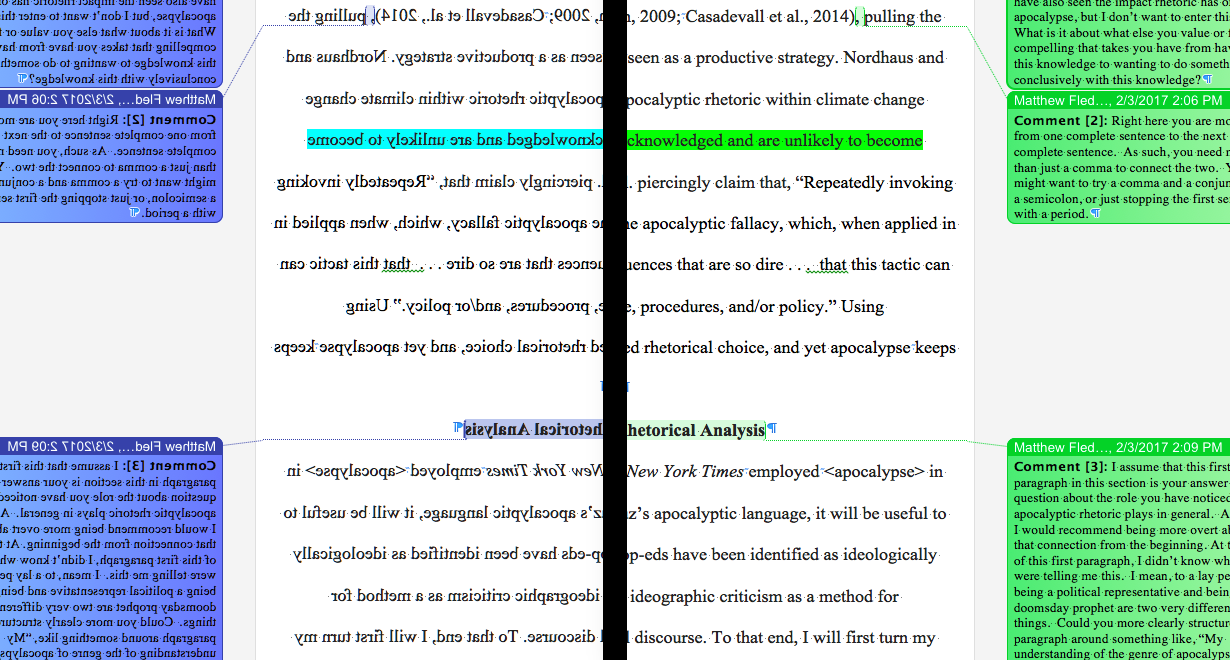

Whether I’m responding to a piece of writing as a composition teacher or as a writing center tutor, my comments look similar. I plug in Microsoft Word’s two-toned comment bubbles and write things like, “Hmm . . . I’m not sure how this sentence connects to the purpose of the paragraph. Could you make that connection clearer, cut this sentence, or fit it into the next paragraph?” I use different colors to highlight lower-level error patterns. I compose a summative note about my overall impressions of the piece and recommendations for revision. I email the commented-on document back to the writer.

My responses look similar and do similar pedagogical work, but they aren’t identical. When I compose that summative note as a tutor, I work within a more rigid feedback structure; I identify one strength and two areas to work on. When I’m the writer’s teacher, I’m looser with that template, but as a teacher, I find myself referencing the assignment’s prompt more knowledgeably. It makes sense that my role as a composition teacher and my responsibilities as a writing center tutor should affect my written feedback differently. After all, tutoring and teaching are two different educative processes that come along with different sets of expectations. Tutoring and teaching exist within separate (if similar) contexts. Given all this, I’m interested in exploring how these variations in context, expectations, and responsibilities influence written feedback practices. And I want to consider how reflecting on the differences apparent in our written comments across instructional roles productively inform our pedagogy as both teachers and tutors.

Good Feedback is Good Feedback

The fact that my responses as a tutor mirror my responses as a teacher is unsurprising. Both situations have me engaging as a curious reader with a writer’s text. Nancy Sommers, in her canonical article “Responding to Student Writing,” asserts that as composition teachers “we comment on student writing to dramatize the presence of a reader, to help our students to become that questioning reader themselves” (148). Whether as tutors or teachers, we show up as generous, responsive readers.

As a result, the reading and responding practices we employ as tutors and teachers share a common set of priorities. These commonalities become particularly apparent when we consider how the advice for good written feedback is the same for tutors and teachers. In her (highly recommended) book The Online Writing Conference, Beth Hewett forgoes distinctions and says that she is writing for “teachers/tutors” (3). What she has to say about responding to writing through online mediums (i.e. email, screencasts, and synchronous technology) is equally applicable to people in both instructional roles. Similarly, the great advice that Washington University in St. Louis provides its teachers on how to productively comment on student papers could just as easily be recommendations for tutors preparing to write comments on a tutee’s text.

As a result, the reading and responding practices we employ as tutors and teachers share a common set of priorities. These commonalities become particularly apparent when we consider how the advice for good written feedback is the same for tutors and teachers. In her (highly recommended) book The Online Writing Conference, Beth Hewett forgoes distinctions and says that she is writing for “teachers/tutors” (3). What she has to say about responding to writing through online mediums (i.e. email, screencasts, and synchronous technology) is equally applicable to people in both instructional roles. Similarly, the great advice that Washington University in St. Louis provides its teachers on how to productively comment on student papers could just as easily be recommendations for tutors preparing to write comments on a tutee’s text.

And yet, as Dave Healy assured the writing center community back in 1993, the writing center and the classroom are different (if complementary) spaces. Despite the similarities, writing center tutors and composition teachers are subject to different responsibilities, contexts, and expectations. Which reaffirms the question, “How does our feedback change across these different spaces?”

A Questionnaire

To pursue this question, I asked several of my writing center colleagues to fill out a little questionnaire. I asked them how long they’ve taught composition, how long they’ve been responding to writing as a tutor, and what they see as similarities and differences in their written feedback across instructional roles. The six folks who responded were Maggie Hamper, Zach Marshall, and Aaron Vieth (from the writing center at UW-Madison) and Jen Finstrom, Hannah Lee, and Mark Lazio (from DePaul University’s University Center for Writing-based Learning [UCWbL]). Collectively these six tutors/teachers have accrued 23 years of composition teaching experience and 31 years of responding to writers’ papers through writing as tutors.

The similarities these educators found between the comments they write as tutors and as teachers are plentiful. Whether they are functioning in either role, they use their written comments to prioritize the writer’s growth and not just the writing’s development. They identify specific strengths within the texts. They use their comments to draw attention to genre conventions and rhetorical awareness. They ask questions as a way of fostering dialogue. Stephen North and Peter Elbow would be proud.

But all of the survey respondents also acknowledged that their feedback is not identical between their two educational roles. Context changes things. In particular, respondents report that their feedback as composition teachers is altered by their closer relationship to the writing assignment and by their ongoing interactions with the writer.

“Owning” the Prompt

When it comes to the prompt, the tutor is an outsider whereas the teacher is the ultimate insider. As Jen writes, “I know what I’m looking for with my own assignment.” The teacher has concocted the prompt and wields the responsibility of evaluation. This ownership and responsibility gives the teacher an authority over the drafted text that a tutor simply does not have.

For several of the survey respondents this altered relationship to the prompt opens up the possibility for more directive comments. Mark says that he is “more likely to say something more directive of what should be done with the paper when I’m teacher commenting.” Jen writes, “I think that I’m a bit more directive at times in student drafts (though not always).” Conversely, Zach takes a different approach on this topic of directness, reflecting that whether he’s a tutor or a teacher, “I always try to be direct with the way I phrase my advice: not ‘you might consider x’ but ‘you should do x because . . .’—I’ve found that being directive doesn’t do the work for students (as some people fear) because there are still many steps between my advice and a better draft.”

For several of the survey respondents this altered relationship to the prompt opens up the possibility for more directive comments. Mark says that he is “more likely to say something more directive of what should be done with the paper when I’m teacher commenting.” Jen offers the same sentiment, writing, “I think that I’m a bit more directive at times in student drafts (though not always).” However, this trend isn’t true for all the respondents. Zach takes a different approach on the issue directness in general. He reflects that whether he’s a tutor or a teacher, “I always try to be direct with the way I phrase my advice: not ‘you might consider x’ but ‘you should do x because . . .’—I’ve found that being directive doesn’t do the work for students (as some people fear) because there are still many steps between my advice and a better draft.”

Zach’s embrace of direct comments across pedagogical roles resonates with what Beth Hewett has to say on the issue. She has a whole section in The Online Writing Conference about using direct over indirect language in our written comments (116-129). However, Mark’s and Jen’s sentiment still ring true to my own experience. As a teacher, I’m more willing to gravitate towards directive feedback. As a tutor, I balk at imperatives and default to questions and suggestions.

Perhaps our willingness to be directive in our feedback is a function of our increased knowledge of the writing’s content and context. Of course, this increased knowledge connects back to our relationship to the prompt. Aaron reflects:

When I am responding to writing as a teacher, almost all of the time I do know what the student is saying when their prose is unclear, but I will still address vague or unclear phrases. Usually this feedback is phrased like: I understand that you are trying to say x (which is a great point), but this is not clear the way it is worded. Here is how someone could read this to mean y. I suggest fixing z or choosing a different word for z or whatever.

When I address clarity as a tutor, I usually do not know what the writer intends to say. My feedback in this case will point out the unclear language and might offer a few possible readings if I can clearly imagine them. Frequently, though, I am unable to imagine possibilities in these cases and have to rely more on pointing out exactly what language is unclear. In these cases, I think my feedback is more limited because it is hard to offer suggestions when I can’t tell what the student wants their essay (or whatever) to do.

As teachers, we know what the evaluative reader thinks the writing should be doing since we are that reader. This clarity encourages some of us to more directly assert what is and isn’t working in this text. But the assignment isn’t the only thing we tend to know better when we’re the teacher; we also know the writer. And this relationship can influence our feedback as well.

Knowing the Writer

According to Mark, when the writer is his student, he’s more blunt; “not rude or short,” he clarifies, “but just me and to the point. The student already knows me and we have a bit of a relationship started by the first round of commenting . . . As a tutor I am more aware of the peer role, and I don’t have any idea how this person will react, so I’d say I’m more cautious with phrasing.” Mark mentions that knowing the writer also means knowing the writer’s previous work. Whereas in one-off appointments at the writing center there is no shared history from which to draw, in classroom commenting, there is.

Interestingly, while the relational connection between teacher and student might be more enduring than that between a tutor and a tutee, this does not necessarily translate into more writer-centered comments. Maggie recognizes that when she comments as a writing center tutor, she pays more attention to the writer’s concerns. Conversely, “I don’t often ask my students—what are you concerned about with this draft? (Though I probably should!)” Perhaps this connects back to a teacher’s knowledge of the assignment. When we’re the ones who generate the prompt and (as Hannah identifies) hold the evaluative authority of grading, it’s perhaps easier to place a premium on our recommendations over any concerns the writer might have. Perhaps our knowledge of the writer does not supplant our knowledge of the prompt.

In my own practice, knowing the writer means I feel the freedom to be a little more informal. I don’t have to spend an opening paragraph situating myself in relationship to the writer and the text. The writer knows who I am and (I hope) trusts my capacity to provide productive feedback. Additionally, knowing the writer means I know that our interactions will extend beyond this particular draft. I will see the writer in class that next week, so I can ask, “Does that make sense?” as a tag at the end of a comment and genuinely mean it. There is an expectation for an answer–whether a direct answer through a follow-up email or after class conversation or an indirect answer through a subsequent revision–that doesn’t exist in the writing center context. Knowing the writer means being additionally accountable to that individual’s writing development as instrumentalized through that piece of writing.

Further Questions

Of course, while we’ve been considering the differences, we shouldn’t lose sight of the many similarities. As Zach reflects, “my writing center tutoring has so deeply informed what I do in writing classes because I’ve had so much more success with methods I learned as a tutor.” The best practices for providing written feedback suggest that we can and should be bringing our tutorial sensibilities into our composition courses. Although, how can the skill transfer be productively turned the other way? Should who we are as teacher commenters inform our practice as tutors? Beth Hewett would perhaps suggest that we bring that directiveness some of us feel more comfortable with as teachers into our writing center repertoires. As you reflect with me on these issues, I’m interested to hear your thoughts on any of these issues or in response to these questions:

- How are your written commenting practices different when you’re a tutor and when you’re the writer’s teacher?

- How might our “best practices” for composing feedback shift in response to the changing contexts of composition teacher and writing tutor?

Writing in response to writing is such an integral way that composition is taught. Whether these commenting processes take place within the writing center or in the classroom, I believe we should continue considering how these shifting contexts and roles might alter or affirm our pedagogical practices.

Works Cited

Healy, Dave. “A defense of dualism: The writing center and the classroom.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 14, no. 1, 1993, pp. 16-29.

Hewett, Beth. The Online Writing Conference: A Guide for Teachers and Tutors. Macmillan Higher Education, 2015.

Sommers, Nancy. “Responding to student writing.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 33, no. 2, 1982, pp. 148-156.

Thanks for this post, Matthew. This got me thinking a lot. For me, the difference between a tutoring session and a course is like that of a short story and a novel. In the session, I am making sure every moment and move matters. I feel the need to understand the assignment and writer as quickly as possible, make strategic choices about what to cover and how deeply, and get straight to the point. I am much more direct. I also cling to the prompt much more because I don’t know if the instructor/ professor likes surprises and also because as an outside reader I feel that’s one of my uses– I can usually see when something is going off track or not following directions.

As a teacher, I think I spend a lot of time getting to know students and building a relationship with them. I comment mostly on ideas and logics that one might see as “big picture” concerns. And I deliberately write assignments to be open ended so that I am surprised. As I tutor I want the assignment and the prompt to match, in other words. But as a teacher, I know myself and I know I am flexible about what a project ends up looking like. I have the luxury of valuing creativity and critique. Therefore, my feedback tends to be in the form of questions asking for more depth and development, more detail. My feedback also depends much more on the individual person’s take on the project than the project itself. As a teacher, I want every assignment to matter to that student– as a tutor, I hope for that also, but I also just want them to do well. To put this another way, I am also able to balance short-term concerns vs. long-term concerns. In the session, although I make an effort to have “mini lessons”, my frame of mind is much more on the moment. What will help this person now? What will help this person on this specific paper?

Part of these choices may also be due to the in-person (usually) nature of the session vs the private letter writing style (usually) of teaching. I think public, private, and face to face change feedback, too. In person, whether tutoring or conferencing, I can be direct because I can also smile and read the person’s facial expressions and body language. On paper, via “grading” or online tutoring, there is no improvising or adjusting until next time, so I tend to give more reassurance and encouragement. One benefit from Skype has been that now I use Google docs in my classes and also incorporate more modes of delivering feedback. These are just my own tendencies, and I appreciate that your post made me consider them.

Virginia, I find your tutoring-is-to-short-story-as-teaching-is-to-novel analogy really compelling and apt. (Exploring that further would make for a great blog post!) It makes sense that the long-form relationship of teaching allows for more instructional subplots than does tutoring. Thanks for sharing this intriguing way of framing these differences!

Thanks for such a thoughtful post, Matthew! You’re touching on some really important things that I want to consider in both my classroom and tutoring practice. I found myself agreeing with Mark’s and Jen’s default to questions and considerations when responding to writing center drafts of students we may not know; however, Zach’s comments about offering direct feedback remind me that I should always offer direct options to demonstrate different possibilities. In addition, your point about relationships is so, so important, and something I try to always cultivate *especially* in online spaces. I empathize with Maggie’s point about not asking classroom students as much as I should about their concerns with a draft—a question I definitely want to incorporate more in my classroom teaching. Finally, I just wanted to say that I loved your research design motivating this post! It’s great to hear and learn from smart folks we know in the UW-Madison writing center!

Thank you, Stephanie! In regards to the research design, getting to hear specific insight from tutors I respect was a really rewarding part of writing this post. It was also enjoyable to make connections across writing centers and bring folks from DePaul’s UCWbL into conversation with TAs at UW-Madison. I’m certainly blessed to have been so consistently surrounded by tutors and teachers whose work I admire!

Great post, Matthew! I wish I had a clearer response for you about how my teaching informs my tutoring commenting, but there’s one thing I’ve noticed about how my tutoring work has informed my teacher-commenting that you didn’t mention directly, so I thought I’d leave it here: one thing that tutoring has helped me to do is to make sure that I’m leaving lots of room for writers to have authority over approach and ideas. In the classroom, I find the pull to be directive stronger because, like many of your participants mentioned, I know the context and the assignment better. I don’t have my own class this semester, but the last time I taught, while commenting on drafts, I tried to be more tutor-y, by which I mean I tried to (within parameters, of course) approach commenting as if I weren’t the instructor. I don’t know how well I was able to shake that teacher identity or whether it’s even something I should want to do, but I did find it helped me to expand my ideas about what a “good” response to my prompts should look like. In other words, trying to comment like a tutor rather than a teacher was a helpful exercise for me because it reminded me to leave as much room as possible for student genius. Not that my students aren’t genius anyway, but still – it helped me to be more open minded.

Leigh Elion

Writing Center Instructor

PhD Candidate, Composition and Rhetoric

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Thanks for these thoughts, Leigh! This makes me wonder how your students might have responded (differently?) to your purposeful move from teacherly comments to tutor-y feedback. And that makes me think about what a study investigating that question would look like. One that focuses on the students’ experiences and contrasts the perceived or actualized influence of different “genres” of feedback . . . It’s great that this process of altering feedback styles informed your thinking, and I wonder how it might have altered theirs . . .

More thanks and praises for composing these insights, Matthew! I find myself thinking about the feedback I give as a tutor against the written comments I provided students as a literature TA (where much of my commenting experience lies). More often than not, those assignments (which I knew well but certainly did not “own”) didn’t incorporate drafting or revision phases, and the comments I provided came with a grade. Reflecting on it, I’m not thrilled to think just how much my comments were informed by the evaluative mark accompanying them – almost a defense of the grade, whatever the grade, saying “Here’s where this writing falls within the rubric and for these reasons” – rather than by the student’s development as a writer. I’m realizing now ways in which my tutor feedback practices could have helped me maintain a more formative approach, looking forward to future writing assignments for the class or (even better, as assignments often differed significantly in form and function) providing a rhetorical frame for considering the discipline-specific characteristics of the assignment that the student might use in approaching writing in other courses. I’ll certainly be thinking more on this!

Thanks for your thoughts, Angela!

Certainly commenting-in-order-to-justify-grades can be a major motivating force for written feedback. And that evaluational exigence drastically influences the kind of comments that get made–as does the fact that papers at this stage are often not revised. Which is why requiring multiple drafts that aren’t graded but are commented on is so important. Or structuring course evaluation through contract grading.

But I’m intrigued by this other role you raise–the role of the TA in the large class who doesn’t “own” the assignment but is still closely involved in the process. I want to think more about how that role is and isn’t like commenting as the primary teacher . . .

Thanks, Matthew, for collecting so many voices for this post. I find myself drawn to Mark’s comment that how much you know the writer makes a great difference. I didn’t originally think about this when I responded to your questions, but I think it’s such an important point because relationship does change how I respond to writing. Part of our struggle as tutors is reaching people we hardly know with good advice. We’re like friendly strangers.

And yet, as I reflect on how my relationship with a student changes how I approach my written responses, I don’t think that I am more direct with students I know well. As I think about my most recent semester teaching, I remember that I drew away from directiveness as the semester advanced. I found myself asking students in late-semester conferences, “What do you expect me to say based on what I’ve said in the past?” In other words, I found myself retreating into more of a questioning tutoring strategy in order to pull some of my scaffolding away. My approach sounds counterintuitive to me (directive with strangers, purposefully ambiguous with students I know better), but I also think it makes sense in terms of long-term learning.

Zach, I really like your “What do you think I would say based on what I’ve said before?” strategy as a way of encouraging students to think critically about the way readers might critically approach their writing. I’ve done a similar thing during late-semester peer review by encouraging my students to think about the way I’ve been commenting on their work and attempt to channel me in some of their responses to their peers. But posing that question directly to the student writer seems like a potentially rich and productive practice.

In your experience, how have those students then responded to your question?

Dear Matthew,

I teach Applied Linguistics at a German university, so I am neither a composition teacher nor a writing centre tutor (albeit with a training background in writing consultancy). However, I integrate writing assignments and feedback processes into my content courses.

Your post popped up on my RSS reader at the right time: I had just finished a blog writing project (https://lama.hypotheses.org) in an introductory Applied Linguistics course (Master level) that involved a good deal of peer, reader and teacher feedback. Teacher feedback was provided by myself and, to some extent, by a colleague of mine. The questions you raise in your post resonate with me as similar questions came up during and after this project.

I approached the feedback task with good intentions and high expectations: Unlike the rather unstructured, direct comments and symbols I place in the margins of graded term papers, I intended to give non-directive, non-judgemental, person-centred feedback with the aim of fostering the writers’ autonomy and responsibility for their texts: e.g. by communicating my general impression of the text, describing why I, as a genuinely interested reader, think X is not clear yet, asking if they can imagine placing paragraph Y elsewhere, suggesting an alternative expression Y etc. Since the texts were not to be graded, I thought I could easily leave my teacher (‘judge’) role and assume a tutor (‘coach’) role instead.

However, reality hit me very hard. I had scheduled my feedback towards the end of the project (3rd draft). Peer feedback had occurred twice before (online and face-to-face), plus there had been one round of questionnaire-based feedback by our ‘test readers’, a group of English students from a local secondary school. When it was my turn, it turned out that while a couple of posts were, as I had expected, indeed in a final draft stage, the others were still in a rather early draft stage and required a good deal of further revision before they could be published.

I commented on all text levels: from global, structural features and content issues down to surface and mechanical errors (vocab, grammar, spelling, referencing, lay outing). In order to accelerate the revision process (the students were supposed to present their text to the public a few days later), I eventually ended up making quite a number of blunt commands and, I have to admit, rewriting whole sentences occasionally. I unpacked the scaffolding again that I had gradually put away as the course progressed; I (thought I) even had to take trowel and mortar in my own hands in some cases. And yet still some of the posts went back and forth between the authors and me several times before they were released to the public – here I fully agree with Zach when he says that “[he has] found that being directive doesn’t do the work for students […] because there are still many steps between [his] advice and a better draft”.

As the blog could also be regarded as a marketing tool for our MA programme and our discipline in general, I felt a lot was at stake not only for the students, but also for me/our AL chair (a fact that reminded me of the concerns regarding blogging raised by Deborah Brandt whose post http://writing.wisc.edu/blog/?p=4578 I had discussed with my students…).

Upon project completion I asked myself the following questions: Why did I diverge from my tutoring principles? Did I go so far as to appropriate my students’ texts in some cases? Why did the earlier peer feedback not lead to more ‘final’ texts? Were my expectations simply too high? Was it because the students were writing in their L2? Because it was a collaborative writing project? Should the teacher feedback have occurred at an earlier stage? Is it okay for me to add direct(ive) comments and do a considerable amount of editing? Do I have to assume the role of an editor (=gatekeeper?) if the texts are to be published on an institutional website? Time-wise, I have to admit, it is not something I could do on a regular basis for a whole class. And it wouldn’t help achieve one of the major goals I have in mind when giving such writing assignments: Help the students turn into authors who create their own texts, with their own voices, carefully guided by their peers and teachers. Can I, as the person who has designed the course and the assignment, leave my teacher role after all? Or are the coach and the judge roles simply irreconcilable?

I will continue pondering about these questions, and I’m looking forward to any responses by other teachers and tutors that have had similar experiences!

__

By the way, I’ve been trying to find a way to change the colour of the comment bubbles (Word 2010) to be able to differentiate between different comment types (as you describe at the beginning of your post), but even Google couldn’t help. Is this a feature of a more recent Word version or do I need some IT help?

Stefanie,

Thank you so much for sharing your experiences in regards to the challenges of providing written feedback! You offer some really compelling ideas and questions that further my line of thinking in some unique ways.

I think you’re really on to something in regards to how the publicity of a piece of writing changes the way we comment on it. Since your students’ writing would appear on a public blog that is used to promote your program and therefore (at least in part) you, your motivation for commenting was wrapped up in your own sense of public identity in a way that it’s not when we’re just commenting on course paper. It sounds like you wanted to make sure that this writing was “right” not just for the students’ potential learning experiences but because you had something at stake in their clarity of ideas as well. I think this is just another (striking) example of the that context influences our feedback strategies.

(And here’s some information about how to change the color of your comment bubbles in Word 2010: http://suefrantz.com/2011/12/03/qtt-change-comment-color-in-word-2010/ .)

Matthews, thanks for your thoughts! You’re absolutely right, it seems clear to me now that the publicity aspect is the most obvious reason for my divergence from the tutoring principles. I’m quite convinced that had the texts only been written for the class as an audience (or maybe a specific group of pupils), I wouldn’t have been so nervous about their ‘good’ quality. So is extra work for the teacher then the downside of having student texts published…? Next semester I’m going to change the assignment a bit, and I’m curious how this will work out.

Thanks for this post, This got me thinking a lot. For me, the difference between a tutoring session and a course is like that of a short story and a novel. In the session, I am making sure every moment and move matters. I feel the need to understand the assignment and writer as quickly as possible, make strategic choices about what to cover and how deeply, and get straight to the point. I am much more direct.