Jessie Gurd is the 2014–2015 TA Coordinator for the Online Writing Center and a PhD student in Literary Studies; she has been an instructor at the Writing Center since the Fall of 2012. Jessie studies early modern English drama with a focus on ecocriticism and spatial theory. You can find her on Twitter @jesstype.

Jessie Gurd is the 2014–2015 TA Coordinator for the Online Writing Center and a PhD student in Literary Studies; she has been an instructor at the Writing Center since the Fall of 2012. Jessie studies early modern English drama with a focus on ecocriticism and spatial theory. You can find her on Twitter @jesstype.

If the image above is any indication, I am definitely away right now.

It is midmorning here in Bermuda—still early back home in Wisconsin—and my “office” affords a view of the harbor and the hotel pool deck. We are just on the edge of Hamilton proper, so the noise of a small city occasionally leaks through the wind, birds, and tree frogs. For the past few days, I have woken, made a cup of tea, and come out on our little balcony with my laptop to work.

Technology makes it not only possible but fairly easy for me to keep up with my work as the Online Writing Center’s TA Coordinator from here. Even in Madison, my trips to campus are relatively infrequent, and I assess the queue of requests for email instruction much as I do here: with my first cup of tea. Being so very away right now and yet having much the same experience I do at home highlights the perspective my position affords. Even when I am on a laptop in the heart of the brick-and-mortar Writing Center on campus, I am working at a distance.

The distance from which I work allows me to see the work our tutors do with students online, especially in email instruction. I don’t pick through drafts and responses or make out like some kind of Sauron, but I do attend to the exchanges to ensure we maintain the high standards we set for our tutoring. This time of year, we see a lot of applications in the Writing Center. Both online and in person, we work on applications for law, medical, and pharmacy school; physics, history, and curriculum and instruction doctoral programs; grants, fellowships, and tenure-track positions. Cover letters, CVs, and resumes always find their way into the mix to supplement the essays and statements.

Thinking about the position I am in as the Online Coordinator, watching these exchanges, seeing new drafts and then revisions of those drafts come through my inbox, makes me remember an Another Word post from Rachel Herzl-Betz in which she describes love of the personal statement and other application essays. One of my favorite moments in the piece is when Rachel quotes Michelangelo: “I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.” Rachel observes that “the best essays reveal and magnify the natural contours of a life, cutting out the background noise so that readers see how a favorite book in fifth grade connects to the business plan five years down the line.” Now that I have more experience in these devilish genres, I see even more clearly the wisdom in Rachel’s approach and the confidence she must foster in each of her students. From my Coordinator’s-eye view, I witness tutors and students freeing angels, as it were. However, hands-off as I am, I witness something else, too: I witness a lot of identity-building.

“Identity-building”—deceptively simple, but any good writing tutor knows we need a definition for such a term. Honing a piece that falls under the generous aegis of application material writing obviously engages the writer’s identity. As a tutor, I ask questions, inviting student writers to bring their ideas and experiences out into the light by telling stories, sharing facts. These are just fragments of a writer’s identity that, when selected, shaped, and placed together are somehow supposed to stand in for an entire person. The tutor’s involvement in this process is also a kind of identity-building: on the fly for that particular session or student, to be sure, but also in a way that will be sustained and contribute to the tutor’s future pedagogy.

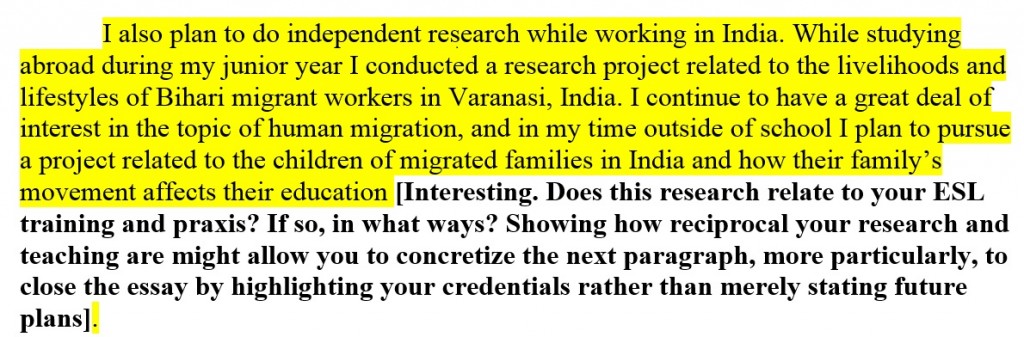

Here, Lydia Greve, an undergraduate student at UW-Madison applying for a Fulbright scholarship (best of luck, Lydia!), outlines her plans for her time abroad in India. Manuel Herrero-Puertas, one of the fantastic tutors on the email instruction team here at the UW Writing Center, responds in bold and between brackets. In the piece, Lydia shares critical interest in migrant workers and education, which dovetails in really exciting ways with her passion for participating in and building community locally and globally.

Manuel offers immediate praise, then proceeds with questions to get Lydia thinking about other stakes to which she may need or want to attend. As he explains, addressing those questions (or some like them) will strengthen the conclusion of her essay, and thereby the essay as a whole. What Manuel shares with Lydia is not a short laundry list of more information to cover, but rather a goal (here, setting up a strong final paragraph) and questions that, if answered, model the kind of work Lydia can do to achieve that goal.

From my position, I can also trace the same kind of work outside of its most obvious realm (application materials) and into other forms of written work.

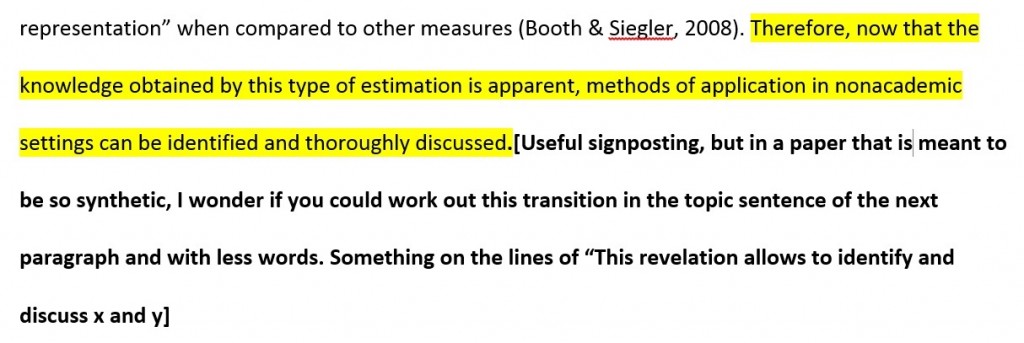

In this example, Jacinta Gilmore, an undergraduate student at UW-Madison who is working on a paper about line number estimation for a 500-level educational psychology course, concludes a paragraph with the highlighted sentence. To my eye, Jacinta demonstrates her solid grasp on the material, and Manuel’s immediate and specific praise reinforces my reading. He identifies what the sentence is and its use in an essay: it is signposting. Effective signposting is not easy; it tells your reader what something is, how it fits the rest of the material, and why that thing is important. Manuel helps Jacinta improve what she has by suggestion that she simplify the sentence and move it around—that is, make the signposting a little more obvious. In his example, Manuel models how to get to the meat of the sentence and make it pithy (something the prompt for the assignment required).

Both student writers must communicate something of themselves to the reader. In Lydia’s case, she is working on a personal statement; the whole point is to communicate something of herself. In Jacinta’s case, she is proving with every sentence that she can and has synthesized the material, that she can and will share its substance and her own critical insights. In his responses, Manuel also communicates something of himself. As a tutor, he has expertise and authority; he challenges his students in their work. He is also extremely able in the more difficult part of the project: giving these student writers something to reply to and helping them take on his authority to shape their own writing.

Like revisions to a draft, our writing pedagogy evolves every time we sit down at a table or a computer. We work on tone, on style, on genre. We adjust, develop, and tweak, discarding what doesn’t work for us or our students, keeping and reshaping what does. I reflect on this process in my own tutoring, but I get to see it in action from the email instruction team just about every day of the week. The way that our own tutor identities are shaped side-by-side with our students’ is most obvious during this application-heavy time of year, but, as the exchange between Jacinta and Manuel demonstrates, that process is always happening.