By John Tiedemann

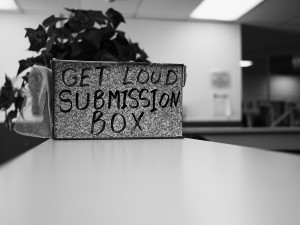

Stories without Homes

“Are you writing the real story here?” the man at the door asked.

I didn’t realize at first that the question was addressed to me. I was sitting at a little plastic folding table at the entrance to the Saint Francis Center, Denver’s largest daytime homeless shelter, where each Monday and Friday the DU Community Writing Center sets up shop. Beside me sat a woman writing a letter of apology to a staff member at another shelter, a condition of her readmittance after having shouted at him the week before. Behind us sat another woman, not writing but resting, after I’d helped her apply Bactine and a Band-Aid to the cut she suffered when she fell down outside the shelter doors. Across the table sat Mairead, a graduate teaching assistant who’d started working at the Community Writing Center just that day; she listened intently as John, a homeless Navy veteran and one of our regulars, outlined the chapters of a book he’d been working on all year. Nearby stood another fellow, who intervened intermittently to explain that he was the true author of the lyrics to Pink Floyd’s The Wall.

And so, preoccupied as I was with the several simultaneous conversations at our table, and surrounded by the ambient noise of the shelter, where a hundred and fifty, maybe two hundred people filled a space of about a thousand square feet, talking in groups around long tables or sitting alone in scattered chairs, I didn’t realize that the man at the door was addressing me until he repeated his question:

“I said, are you writing the real story here?”

The man — I’ll call him Martin — was visibly distressed, but his tone was calm and commanding, the voice of a person accustomed to having his questions answered, and quickly. Uncertain what he meant, I asked, “Do you have a story that you’d like to write?” But Martin brushed my question aside: “It says on the sign that you’re the ‘Writing Center,’ and I want to know if you’re writing the real story here. Because people don’t know what’s really happening, and they need to understand. Are you reporting that?”

I invited Martin to sit down and explained what we did at the Community Writing Center, how we didn’t assign stories to our visitors, let alone act as “reporters” ourselves, but rather sought to help writers in whatever way they wanted with whatever writing they brought in.

Martin seemed disappointed, but he proceeded to tell his own story nevertheless. He had made millions in real estate, he said, refurbishing and reselling old mansions, but he lost it all in the crash of ’08. He had been a prominent social psychologist, he said, specializing in the psychology of homelessness, but now he was homeless himself. He had sat on the mayoral commission that had launched Denver’s 10-year plan to end homelessness, he said, but then he found himself living in his car and, after the car was stolen, on the street. Growing more agitated with each turn of the tale, Martin sometimes sobbed when he spoke, as if pleading to be heard, and sometimes barked his sentences like commands, as if signaling to a subordinate, Hey, you ought to be writing this down.

“I’ll show you,” he said finally. “This is real. Wait here and I’ll show you.”

Martin left abruptly, and, to be honest, I didn’t expect him to come back. One tries to suspend judgment about the veracity of the stories one hears in shelters, where tales so harrowing as to beggar belief are all too often all too terribly true. However, Martin’s story seemed to me to conform to a familiar pattern. Like the story of the other fellow at our table, who had succeeded in persuading himself that he had written a multi-million-selling album in part, no doubt, through the very process of repeating that story to others, Martin’s story appeared to be a repetition and a displacement, an attempt to work through the formless, overwhelming experience of the trauma of homelessness by reiterating it compulsively, slightly altered each time, until it took on an aesthetically balanced, hence emotionally manageable, form: Who is now poor was once rich; who is now homeless was once a real estate tycoon; who now suffers was once counselor to the suffering. I didn’t expect Martin to come back that day. Perhaps in a week, or a month, after enough time had elapsed that he could forget he’d told me his story already and so could tell it again.

I was wrong. Martin returned within the hour, two documents in hand: a diploma certifying his doctorate in psychology and a feature story clipped from the newspaper and laminated for safekeeping.

Everything Martin had said was true.

The newspaper story was a years-old human interest profile, describing Martin as a psychologist who had worked with the homeless before going into real estate in the early Aughts, when fast fortunes could be made flipping houses. He’d put part of his profits into creating housing for the homeless, and, as a result, the mayor had asked him to serve on the commission charged with devising the city’s homelessness plan. The article was a feel-good piece, a flattering portrait of a self-made millionaire giving back to the most vulnerable in his community. No wonder Martin had laminated the article to keep it safe; no wonder he held it on to it even after he’d lost everything else.

Of course, this profile was published before the second part of Martin’s story unfolded. It didn’t describe how he, like so many of the period’s overnight millionaires, had really been only a millionaire on paper, overleveraged, living from house to house as he refurbished them, plowing the money from each sale into the next project, and borrowing more each time. Those houses stopped selling when the housing bubble finally burst, but the payments still came due; and so the bank foreclosed on one unsold house, then another, and then another, until Martin found himself living in his car. At first, he was convinced that the setback was only temporary, that he wasn’t really homeless, just between houses. Until, that is, the car was stolen and Martin was forced onto the street, where it was no longer possible to pretend that the setback was merely temporary, nor, indeed, that it was a “setback” at all. It wasn’t; it was his life now.

And so Martin found himself at the Community Writing Center at Saint Francis, imploring a tableful of strangers to help him discover “the real story.”

Writing Centers on the Margins

I started the DU Community Writing Center with Geoffrey Bateman (now at Regis University) and Eliana Schoenberg (now at Duke) in the summer of 2008. We had arrived at the University of Denver two years earlier, three of the twenty-one founding faculty of the brand new University Writing Program. Eliana directed the campus Writing Center; Geoffrey and I did a good deal of Writing Center work, too, and, almost from the start, we taught community-based writing courses — me in partnership with Denver Urban Ministries, a food bank where I’d been volunteering, and Geoffrey with Project Angel Heart, a nonprofit that delivers meals to people with life-threatening illnesses. Partly out of frustration with the limitations that the quarter system imposes on community-based projects, but mostly because we believed that Writing Center pedagogies — by nature collaborative, flexible, egalitarian — are uniquely well suited to community work, Geoffrey, Eliana, and I applied for a grant from DU’s Center for Community Engagement and Service Learning to support an 8-week summer experiment. We would attempt to adapt the kinds of teaching that we’d been doing in the on-campus Writing Center — i.e., drop-in hours and workshops — to meet the needs of a pair of daytime shelters for the homeless: The Gathering Place, a shelter for women children and transgender folks, and the Saint Francis Center, the city’s largest daytime shelter, open to everyone, but in practice populated mostly by men.

We didn’t know whether our experiment would work in the long term (or, indeed, at all), but we reasoned that we stood at least a fighting chance. The ability to write effectively is a crucial skill for people seeking to escape homelessness, as well as for the community organizations that assist them. However, the homeless have little access to writing instruction, and organizations that serve the poor can rarely afford writing support for their staff. We knew that we could address those needs, and we suspected that there would be some interest, too, in opportunities to write in more creative genres. So we set up shop and waited to see what would happen, with Geoffrey heading up our site at The Gathering Place and me at Saint Francis.

We had good luck that summer at both sites. At the Gathering Place, an ad hoc writers circle sprang up, with guests composing and sharing fiction (often children’s stories) and personal essays. At the Saint Francis Center, the writing fell into two broad categories. On the one hand, there were résumés, housing applications, letters to lawyers, and so on, i.e., all of the very practical genres of writing required of people seeking a way out of homelessness. On the other hand, there was — well, just about anything you can imagine: poetry, literary fiction, horror stories, sci fi, screenplays, cartoons, song lyrics, philosophical treatises, and more. We worked with staff, too, at both sites, mostly on memoirs and personal essays, but we also offered workshops on aspects of professional writing. By the end of our summer pilot, we knew that we had built partnerships that would last.

What we couldn’t know, however, in the summer of 2008, was that, come fall, the country and the world would enter the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. That crisis was precipitated by the collapse of the real estate bubble that had made investors like Martin wealthy overnight, only to leave them penniless just as quickly. It was the same bubble that had sponsored Denver’s surging economy for over a decade, as what had been the seedy warehouse district of Lower Downtown was transformed into an expensive playground for tourists and shoppers, and as the modest houses and apartments in poor and working class neighborhoods like Capitol Hill (where The Gathering Place is located) and the Five Points (home to the Saint Francis Center) began to give way to luxury condos. In short, Denver’s economy was driven by gentrification, and when house sales and new construction projects ground to a halt, so, too, did the job market. Soon, the wave of layoffs, foreclosures, and evictions that swept through the country swept through town. In the fall and winter of ’08 and ’09, the crowds at the Saint Francis Center seemed to grow larger by the day.

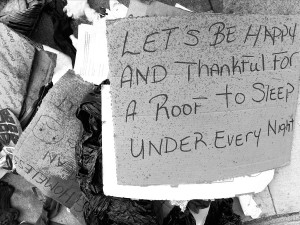

Human Rights/Humans Write: Glen’s Story

Some among those crowds stopped to discuss writing with me and my colleagues at the Community Writing Center. I’ve said that the range of writing we see at Saint Francis is remarkable: from poetry chapbooks to public assistance forms. Perhaps more remarkable, however, is the intense commitment that so many of these writers bring to their work. If you’re like me, putting pen to paper can require an extraordinary act of will; almost anything can seem less daunting than the blank page. I remain astonished, therefore, at the strength of the commitment of the writers I have met at Saint Francis who, not knowing when they’ll eat next or where they’ll sleep, still manage, somehow, day after day, to sit down to compose a poem, or to write the next few pages of a short story, or to revise another chapter in a memoir. It became clear that, for these writers, the act of writing is not only a practical necessity or a creative outlet; it is, rather, a response to a truly fundamental human need, second only to the need for shelter, clothing, and food.

No one felt the fundamental need to write more intensely than Glen, one of our regular visitors. When he first came to the Community Writing Center, Glen was living on the streets; he brought just two pages of writing to share that first time. The pages comprised a short story about a pair of mythical characters called the Shaman and the Page. The Page was a young man in need of guidance; the Shaman was his older, wiser guide. Their story was a parable of sorts, in which the Shaman set the Page to a task he was destined to fail, so that, in failing, he would come to appreciate the gravity of the moral question upon which the Shaman would then expound. After I’d read it, Glen interrogated me about the deeper meaning of the tale: “What do you think this part means? “Did you catch the symbolism in the second paragraph?” He must’ve found the conversation gratifying, because Glen would visit again and again in the weeks, months, and eventually years that followed, always with more writing, always anxious to sound me out, to see whether the deeper layers of meaning were coming across. He’d visit also with my colleagues Blake Sanz, Matt Hill, and Rob Gilmor (faculty from the DU Writing Program who joined the Community Writing Center in our third year), and with the many graduate and undergraduate Writing Center consultants who’ve worked with us over the years, eager to see if the group of us together could grasp the full depth and complexity of his tales. Over time, the story of the Shaman and the Page grew to over a hundred pages, evolving into a Platonic dialogue of sorts, wherein Glen unfolded a personal philosophy rooted in his Native American heritage. Once he found permanent housing through the Saint Francis Center, he took to illustrating that philosophy, too, creating a series of paintings based on scenes from his now epic tale, which he exhibited at a nearby arts nonprofit.

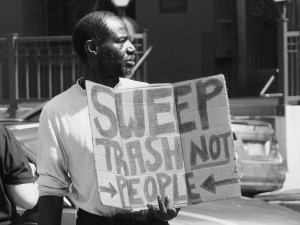

I came to know Glen well during those years. An army veteran and proudly Native American, Glen had moved to Denver after a divorce, taking a job as a traveling salesman. While on the road one winter, he suffered a car accident that put him in the hospital for months. Unable to pay rent while he was laid up, estranged from his family, and with the car that was his livelihood gone, Glen was discharged from the hospital without any money, any prospects, or any place to go. Lost, he came to reside in a homeless encampment near the confluence of the South Platte and Cherry Creek rivers downtown. But it was among the people of the encampment that Glen, a recovering alcoholic, came to discover a new sense of purpose, lending his wisdom and support to others grappling with addiction and the myriad other, seemingly intractable problems that accompany the experience of homelessness. The story of the Shaman and the Page, then, was not only a work of philosophy and of fiction; it was also a work of autobiography, an allegory of Glen’s time in the encampment.

Eventually, the stresses of life on the street grew too burdensome, leading Glen to the Saint Francis Center in search of a more permanent residence. A major source of that stress came from the increasingly frequent police visits to the encampment. The area around Confluence Park was starting to be developed, and the developers wanted the homeless in the area gone, leading to the first of the “homeless sweeps” now commonplace in Denver. There was an irony in this that was not at all lost on Glen: Confluence Park is located at the very spot where, in 1858, Denver City (as it was called) was founded, when land speculator General William Larimer, believing there was gold to be found in the rivers, declared the Cheyenne and Arapahoe seasonal encampment overlooking the confluence to be his own personal property. Driven again by forces of gentrification from that same patch of land a hundred and fifty years later, Glen remarked, meant that his story had repeated that of his ancestors.

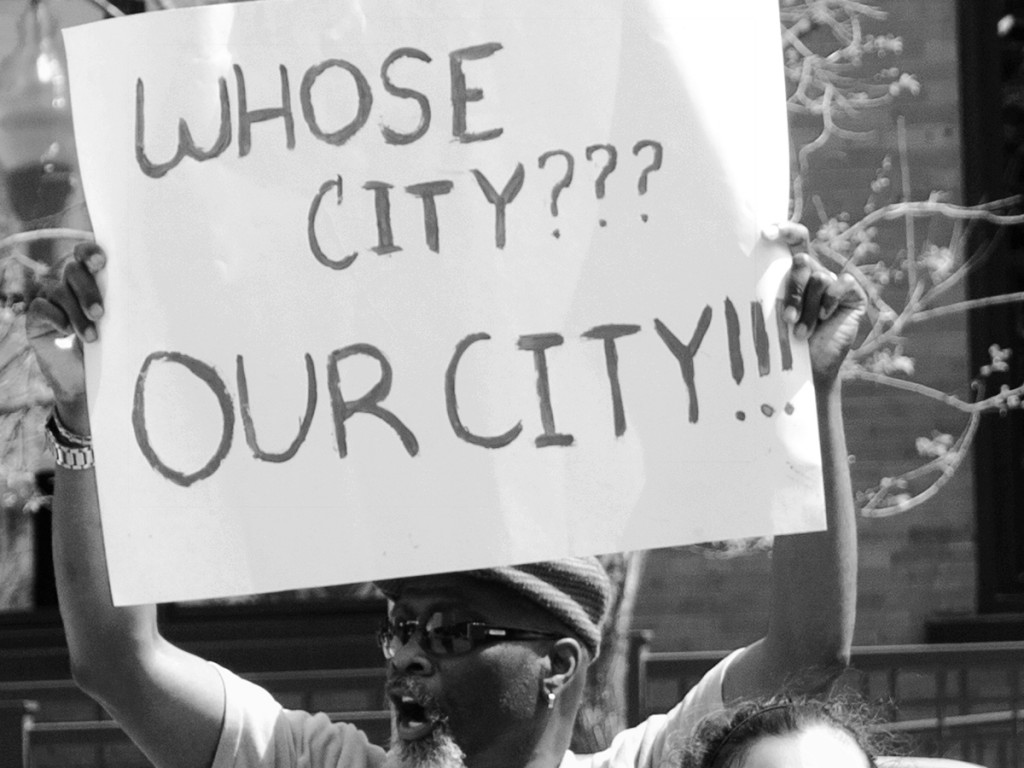

Writing that story was for Glen a form of resistance. As we worked together, I came to understand that, for Glen, writing was part of a multi-faceted strategy to reclaim his personal and cultural history, build a sense of community, and assert his agency. The philosophy that he developed in his writings about the Shaman and the Page became the basis for the discussions he led in a recovery group he had helped to start. It would later inform the talks he was invited to give at EarthLinks, an urban farming nonprofit run by current and former members of the homeless community. The EarthLinks talks soon led to invitations to speak at Denver charitable foundations, which in turn led to Glen’s appointment to the Board of the Metro Denver Homeless Initiative — descended from the same commission on which Martin had served — where he could advocate at the municipal level on behalf of the homeless community at large. In all cases, Glen’s objective was to make his story more inclusive of the homeless community that he had come to represent and to project that story more widely, so that it could be heard by audiences who might otherwise never attend to homeless voices at all. Only through that mutual attention might the repeating cycles of displacement that mark this city’s history give way to the more open, more resilient structures of true community.

In writing that story, Glen’s strategy remained consistent: he would bring drafts of his talks to the Community Writing Center to see if we could discern their deeper meaning, then solicit suggestions for revision with an eye toward reaching an audience still wider and more diverse. It was through working with Glen, and other, similarly committed writers at the Community Writing Center, that I came to understand the uniquely human need that the act of writing satisfies. Glen didn’t write only to express himself, nor only for the sake of the art of writing itself. He wrote in order to find and to make a community. And not a private community, either, i.e., a community made up friends and familiars, but a public community: a community whose members include not only the people that one knows personally, but, more importantly, the people that one does not, even cannot, know personally, except insofar as we all recognize one another as human persons, as members of the human community. The need to feel included in the human community is perhaps the quality that most defines us as human. And it is a need that only writing, in the broadest sense of that word, can satisfy, for it is only through the intercession of writing that a truly public community can be invoked and addressed.

Of course, exclusion from the human community is one of the defining conditions of homelessness. Or, as political scientist Leonard Feldman contends in Citizens without Shelter: Homelessness, Democracy, and Political Exclusion, in a country such as the United States, where human rights are so deeply entangled with property rights, the figure of the homeless person defines our political community precisely by virtue of being excluded from it. Discounted from membership in both the private sphere, through the lack of a home, and the public sphere, via the laws, bans, and other regulations that govern whether and how the indigent can access (or not) and move (or not) within public spaces, the figure of the homeless person is the exception that constitutes the rule: the embodiment of the bare, purely biological life against which the fully political, fully human life of the citizen, i.e., the bearer of rights, is defined.

It is for these reasons that I have come to believe that the writing undertaken by Glen and by other committed writers at the Community Writing Center — whether that writing is a poem, a personal essay, a philosophical treatise, or any other genre (or sui genre) of self-sponsored writing — constitutes a form of human rights activism. In all cases, these acts of writing are an assertion of their authors’ humanity in the face of a social order organized around the denial of that very fact. For these writers, then, to write is to claim the right of access to the public sphere as a basic human right — even when that public is represented only by a few strangers gathered at a folding table in a homeless shelter, struggling together to form a community around a few pages of text.

Coda

Glen passed away in the spring of 2015. He had been living in the permanent housing facility recently built next door to the Saint Francis Center and working part-time at Saint Francis as a Peer Navigator, where he helped guests cut through the byzantine state and local bureaucracies that stand between the homeless and the possibility of housing. When Glen didn’t come to work one morning and didn’t call in, a member of the Saint Francis staff went to his apartment to check on him. Glen had suffered a fatal heart attack the night before. But his spirit, as the Shaman might have said, stays with us: in the writing he left behind; in communities like Denver Homeless Out Loud, an activist group fighting for human rights and against gentrification, and the publishers of a newspaper by and about the homeless community; and, of course, in the Community Writing Center itself, which Glen helped to shape and continues to influence. (And, as I discovered only days ago, in the midst of writing this piece, there is a memorial to Glen on the dedication page of the Metro Denver Homeless Initiative’s 2015 report.)

This has been a shelter story: a story about the stories I have encountered while teaching at a writing center located in a homeless shelter, and a story about how stories shelter us, preserving our histories and vouchsafing our futures, by gathering us together in community. There are many more such stories to be told. So I invite you, in the comments section, to share your own stories, or to remark upon mine, or to pose questions that we can address together.

Oh wow, John. This is powerful. I think Martin was right after all–even if you’re not writing the real story, you are telling a real story that needs to be heard. Thank you for this act of witnessing through word and image. I will share this post with our grad students working on community writing assistance here.

Thanks, Rachel. You’ll have to tell me more about the community work you’re doing. I’d love to hear about it!

I’m going to be thinking about this one for a good long while: “In all cases, these acts of writing are an assertion of their authors’ humanity in the face of a social order organized around the denial of that very fact.”

Going to be teaching this piece later this year, too–thank you for posting, John.

Many thanks, Dan. You’ll definitely want to check out Feldman’s _Citizens without Shelter_. Powerful stuff!

John, thank you for this amazing post. I have to echo Rachel’s comment – these men’s stories, your stories, are so powerful, so real and moving. I have long admired your ability to tell such nuanced and layered stories with your photos, but seeing the photos alongside this text is incredibly moving and inspiring. I hope that you write more about this work that you are doing and have done. I want to hear and see more.

Thanks so much for your kind words, Taryn. I hope to write more about it, too. And to combine words and photos, too. Thanks again!

John. This is outstanding, amazing. Thank you so much.

Thanks, Tiffany — I really appreciate it!

John, what an incredible way to give voice to the writers who seek “an assertion of their humanity.” Like other commenters, I would love to hear and learn more about their stories. I’m reminded of a story that was shared with me by a student who just graduated from DU. He worked all four years of his undergraduate career living out of his truck and is now wanting to share some of his story with the DU community. I feel honored in being able to help him with this. The concept that we write to preserve our histories and to create community is powerful. Thank you for sharing.

Has you’re student found a venue for sharing that story, April? The DU community really needs to hear it!

John – Thank you for sharing this. Two things: as an archivist, it struck me that you (and me, and most others) would recognize Martin’s story as real due to official documents he was able to produce. So often whether or not someone is to be believed depends on whether the proper authority has conveyed that to them through documentation – thank you for telling this story and reminding me/us of this. Second thing: I am now going to bug you about the oral history project we talked about a couple of years ago as a part of the SJ living and learning community. Maybe this time we can get something off the ground. Great story. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks, Kate. I agree completely about the documentation piece of all this and the role it plays in granting reality to stories and, moreover, to persons. Again and again at Saint Francis, we work with writers on such documents as forms, applications, etc., that, at first glance, seem perfectly quotidian, but that occasion quite a bit of anxiety in their writers precisely because of the fear that an error on such documents will result in the negation of their identities, their experiences, their rights. . . . Also, yes: that oral history project needs to move forward!

I enjoyed your article and photographs–you really do seem to be capturing the “real story.” It reminded me of an event where I had the chance to hear some of the Community Writing Center’s clients read their work; their strong writing and obvious pride were equally moving. You and the Center are doing wonderful work, and I’m glad you’re sharing it.

Thanks, Jen. Was that the event at the Press Club, or the one in The Loft. In either case, though: yes, those readings can be really moving, and we should do more of them.

RIP Glen. Whose city? Our city. Get loud, people.

Every time I work at St. Francis, I think of Glen and wish he were still around. He made me laugh and think. He was wise, often without letting on what he knew. He told great stories. He listened so well. Thanks for making him such a centerpiece of the article, John. Remind me one day to tell you the story of Glen’s moonwater project, which he solicited my help with, and which remains a favorite private memory of mine.

I’ll fumble through my comments here John (and other readers), but this piece also resonates my experience at SFC. I had a similar conversation with “Martin” though I didn’t read his authenticating documents. Perhaps he came back after we had closed for the day. Perhaps he had forgotten. Or perhaps he had tired of feeling that he had to authenticate himself through those documents.

Like Dan, I also hope to teach this piece next quarter and will share it with my current students who are struggling to understand the difficulty of, or perhaps even the need for, studying how communities make meaning.

And finally, Glen. The goosebumps and tear begin to form when reading about Glen, his work, and his kindness. I hope never to forget his frequent, full-body laughs, where I worried that he would fall forward on his face or back on his head. He never did.

No, bless him, he never did: he was a gold medalist in full-body laughing.

You, me, and Dan should talk; it’d be fun to think together about creating lessons around this.

Agreed. And I also want to hear about the “moonwater project.”

Looks like I accidentally placed my story comment as a reply to your comment, Blake. Sorry about that.

“Moonwater”?! Now, that’s a Glen-word to conjure with. I’ll definitely have to ask you about it next time I see you.

Really enjoyed learning more about your experiences at the Community Writing Center!

John, thank you for this thoughtful post. I love how through your writing, you connect us, you connect people, and it is because of your writing center work there is more justice for all. Writing, as this post also reminds us, can be about communicating history, personal discoveries, and writing can be about writing, and importantly about social justice and public humanities, but as this post so thoughtfully achieves, writing, as social justice, can be an accounting of a life, writing as an empathic gesture. Perhaps what I like as much if not most of all is how your writing center story makes a place for you, and for Martin, and Glen: like good writing center pedagogy, when a writer feels placed, situated, there is an interaction that humanizes us all in a particular way, a way in which we feel connected to the writer, connected by writing. Your post reminds us, too, how the work of a writing center can be the deeply humanizing work of writing that staves off the banality of numerous predicaments that separate humans from the human community: the work of a writing center can be to foster atonement. We achieve a human reconciliation through writing, through writing with others in writing centers.

Thanks for sharing these remarks, Chris. Although I didn’t situate the piece within the scholarship on writing centers, I feel (as you seem to indicate) that the experience it describes is particularly (for lack of a better word) writing-center-ish. The situated-ness, the embodied-ness, the sense that the relationship is fundamentally ethical, not transactional. One of the side-benefits, for me, of working at the Community Writing Center is that it’s made me better at on-campus writing center teaching and student conferences, too, by encouraging me to see that on-campus work through a wider, deeper framework.

A moving and thoughtful account, John. Thank you for sharing.

Thanks, Heather. I hope we’ll all soon get to read a reflection on your long experience with community engagement, too.

Hi John,

Thanks for drawing my attention to this article. I think it is beautifully and respectfully written. I’m going to forward it to my colleagues here at SLCC.

I was particularly taken by your naming of the self-sponsored writing that takes place at the DU CWC as human rights activism. I couldn’t agree with you more. Your argument is compellingly made and, I think, holds a seed for higher education to take a closer look at community writing possibilities. Absolutely terrific.

Thanks again for sharing with me,

Tiffany

Thanks, Tiffany. Your work with the SLCC CWC has been an inspiration to us all along, so thank you for all you’ve done.

John, I only worked at the St. Francis site for a year, but I remember Glen well. Your writing here is a tribute to him as well as a powerful reminder that we work to help people write, but we also work to be readers for people who need and deserve to be read.

Thanks, Juli> I think that what you say is true. And we’re not only individual readers ourselves, but representatives of the broader public. We don’t always think about our work that way, but I think it’s worth thinking about the responsibilities that go along with that role.

Hi John, thanks for this reflection on your work with the Community Writing Center in Denver. Your piece’s posting was timely, as I was in Durango meeting with the public library about getting a community writing center started there on the same day. It would be great to learn more about your experience starting and sustaining a community writing center project in Denver. All the best to you and others in the program who you are collaborating with!

Thanks, Sarah. Great news about the partnership in Durango! Please do keep me posted, and get in touch if you want to brainstorm, etc.

John, thank you for inviting us readers to join the human community you describe here through your writing. I especially appreciate your attention to the way individual writers can navigate, invoke, and shape the public sphere through stories, regardless of who does–or doesn’t–actually read them.

I wonder about whether and how the fundamental need to write might be expanded to other creative forms of expression. Because such agency is central to being human, I hope that, as readers, we might become increasingly attentive to our responsibilities to listen for voices like Glen’s.

a beautiful and heart-warming story john. i hope it’s ok to share with our homeless efforts group in Guadalajara. the problems we face here are over-whelming.

Yes, of course, please do share it with your group. I’m very glad to hear that it may be of use to them.

Hello John you have brought the real story in front of us.I appreciate your work, your writing will definitely help to improve the life of homeless people.

Thanks for reading, Sam, and for your kind comment.

[…] Rose Pathways Writing Workshop was first conceived by former Writing Fellows assistant director John Tiedemann (now teaching at the University of Denver). John suggested that the Writing Fellows Program could […]

Hi im from Richmond CA grow up all over about to be 31 yrs ol and I still homeless and struggling im a singlr mother of 5kids. I trying to find a way to get my family back together.My last daughter was born March 14 and i have Twins and Iris Twins Im tired of struggling and not having my familys support because everybody has stressed out over me being separated from my kids ive to too many shelters and they dont last forever.. Please help me find some kinda help to get my kids an me a home i know it probley not the first letter from a single mother but i pray you find it in your hearts to listen to my story. Thank you!!

Hi, Diana — I live in Denver, so I’m less familiar with services in California. But I know that the Bay Area Rescue Mission in Richmond, where you’re from, has a program to help women and children find transitional housing. It’s called the Center for Women and Children; their website address is http://www.bayarearescue.org/what-we-do/recovery-programs/center-for-women-and-children. I believe their street address is 200 Macdonald Avenue, Richmond, CA; and the phone number is (510) 215-4555. I hope they’re able to provide help! — John

Just finished reading the story….absolutely beautifully shared. I’m not a writer or a reader per say but I ran acrossed trying to write a paper for my e

English class. Im from California and I live in East Bay. I recently had stayed in the shelters and they are a blessing for a roof over your head as being g homeless is draining physically and emotionally. I can make a list of bad points and good points but instead I’ll share a lil bit about my experience and where i would like to go. I was hit by a car, my right leg was considered degloved. I have my leg n I am blessed to walk again. That accident was April 3 2017..1 am 46 and I was devastated n put into the shelter in a respite bed. I wanted to run but couldn’t even walk I had started using drugs again n knew if I left that shelter my leg would never heal so I became bumble and made a few friends one special friend had a similar healing as mine. we became support buddies joining every group we could laughing together supporting each other in recovery and on hospital visits . Together our friendship became boundless n we encouraged everyone around the shelter…I returned to home to be homeless again but none the less walking again and still surviving I am back in school now n my idea is giving back my friend n I We call ourselves Sheltered Friends. Unfortunately out here in California is n the bay area those shelters are hard to get into and your time usually the s out before you find housing. So I’ve came up with some planes that sheltered Friends can give back in device to help those entering the shelter become more self aware that gangsters do work…I haven’t got it worked yet financially or through paperwork I will probably need help with that but I’m working on it 5 minutes here n there. I’m still in school and should finish in may 2019 if I do finish this degree I already an AA in accounting now working on Business Management. I truly believe my ideas for sheltered friends will really help those entering doors I only hope j to d the means to go about it and do it. To the girl in California best way into those shelters referenced in the Bay Area is to call 211 And ask to be added to wait list n call every evening.. thank you for your beautiful story. Sheltered Friends….justMeLaura u can reach me at p.imperfected@gmail.com.

Thank you for writing, Laura. I truly appreciate your kind words and generosity, and I wish you the very best. — John