By Leah Pope Parker

We learn to write by imitating, by reading, and by thinking about the construction of texts we aim to emulate. It is commonly understood among teachers of writing that learning to write—at a more sophisticated level, in a different style, in a new genre—requires writers to read models for the kind of writing that they want to produce. This is why we use examples when talking about different kinds of writing. In my own teaching, this means bringing in sample paragraphs to help my literature students practice balancing evidence and analysis; it means working with faculty to collect successful samples of scientific reports, application essays, and research papers when we teach writing workshops in courses across campus; and sometimes it even means bringing in sixteen pages of sample resumes and cover letters, so that workshop attendees are able to find a model that at least somewhat matches their discipline and career level.

Asking our students to read models is one of the most impactful ways we can help them develop as writers, and I believe a major part of that comes not just from reading, but from writing in and on our models. My goal in this post is to think a bit about the long history in Western literacy education of learning to write by reading, and particularly by writing in and on the texts that we read. In today’s best practices for writing instruction, both within and outside the Writing Center, writing on our models—in other words, writing in our books—allows writers to closely parse and engage with the construction of an existing piece of writing, so that we might develop our own ways of writing. It is a multifaceted process, which I have seen involve highlighters, sticky notes, doodles, diagrams, and miniature drafts written out between the lines or in the margins. Writing in our books is how many of us become writers of books—and I believe that encouraging writers to write in books (or other models) in a variety of ways can help more of our students become stronger writers. There are, of course, many ways to write in books, which accommodate different learning styles and needs. Here, I want to highlight just three, drawn from my own research.

In a thousand-year-old English manuscript held at the University of Oxford Bodleian Library, I find three models for becoming a writer by writing in books. The manuscript itself, known by the shelfmark Hatton 76, was made in two stages during the eleventh century, and contains Old English translations of Latin Christian texts and Old English compendia of various medicines and remedies. By the thirteenth century, Hatton 76 was in the monks’ library at Worcester Cathedral Priory, where it acquired substantial annotations and glosses from a scribe known as the Tremulous Hand of Worcester, was used for novice scribes to practice penmanship, and became a site where, as the saying goes, there be dragons.

The Tremulous Hand’s glosses and annotations serve as our first medieval example of writing in books to learn to write. A very brief explanation of the Tremulous Hand’s moniker will have to suffice here: he is thus named by modern scholars because everywhere that his handwriting appears across several manuscripts, it is characterized by various degrees of lateral shaking. Scholars of medieval handwriting and modern medicine have suggested he experienced a congenital “essential tremor” that affected his ability to write. But the Tremulous Hand is not only a fantastic example of a real medieval person with a disability who achieved sufficient accommodations to pursue his career, he is also one of the best identifiable examples we have of a late medieval scholar carrying out a systematic program to read Old English (which in the thirteenth century was already rather archaic, due to the language’s shift toward Middle English). The Tremulous Hand’s glosses seem designed to make the texts of early medieval England available to a post-Norman Conquest audience by glossing such texts with translations, altered spellings, and alternate vocabulary that would make them more intelligible to readers of the Tremulous Hand’s day.

Only a few complete texts composed or transcribed in full by the Tremulous Hand survive: an early Middle English translation of the Christian Nicene Creed and fragments of a poem, The Soul’s Address to the Body. The bulk of his “writing” was not what we typically call writing today, but was instead the crucial process of reading models—in his case, the inherited religious, medical, and philosophical wisdom of early medieval England—and marking them up so that they made sense and could be used and read by his contemporaries. The substantial markings made by the Tremulous Hand in Hatton 76, for example, reveal a concerted effort to identify and understand medical remedies for concerns such as vision impairment and eye strain—remedies that would be particularly valuable for medieval monks reading almost exclusively by sunlight and candlelight. Other manuscripts glossed by the Tremulous Hand suggest that he glossed such texts in preparation to copy them out in newly updated language in another manuscript, as he does with his translation of the Nicene Creed. In this way, the Tremulous Hand’s work of writing in books serves not just as evidence of reading, but as evidence of a medieval process of writing.

We still write in our books today, much like the Tremulous Hand, in order to learn to write. I’m including here images of my own recent examples of marking up my books. This practice is immensely valuable for my own writing process, whether I am conceptualizing a larger research project like my dissertation or piecing together a lesson plan. My own practices frequently echo the Tremulous Hand’s, as more a preparation for writing than solely a component of reading.

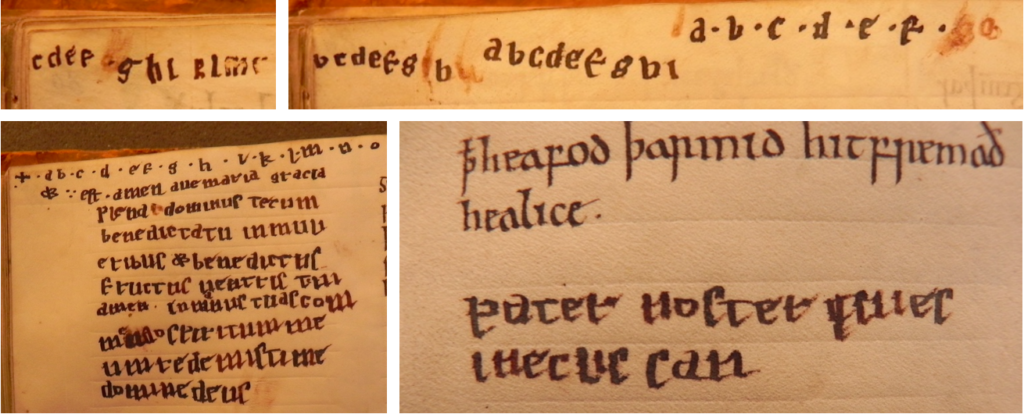

A brief mention of the second and third ways monks wrote in Hatton 76 illustrates this point. The most immediately obvious examples of practicing writing in the manuscript are several points at which open spaces (flyleaves, for example, or blank spaces seemingly planned for illustrations which were never added) were used by novice scribes to practice their penmanship. There are multiple incomplete alphabets, as well as incomplete copyings of religious texts such as the Ave Maria and Pater Noster prayers. Hatton 76 thus becomes a book not just for reading and thinking about writing modified texts, as the Tremulous Hand used it, but also for actively practicing the mechanical skills of writing. While we cannot know whether this writing practice occurred all at once or across several years, or precisely how it might relate to the Tremulous Hand’s work, we can recognize in these brief inscriptions the medieval ancestors of marginal drafting done by modern writers. In my own research, I have written sentences and entire paragraphs in the margins of my books, some of which have even survived intact in the final version of my dissertation. Obviously practicing penmanship and drafting new compositions are quite distinct activities, but I personally feel a sense of affinity for the novice scribes writing in the margins of an old book to improve their scribal skills. Am I really doing something all that different when I write in the margins of my own books, hoping to improve my scholarly writing to the level of what is printed in the book?

I would also suggest that writing in books is not always done solely with letters and words, any more than Writing Center conferences solely rely on written language to do the work of writing. I use diagrams, charts, and other visualizations in nearly all of my writing conferences, and I see no reason why illustration (by an artist more skilled than I am) should not be considered part of the work of writing as well. In this way, sketching, drawing, and even elaborate artistic crafts can be ways of “writing,” or preparing to write, and I believe they should be considered valuable parts of the writing process. This brings us to a third use of Hatton 76 for writing, in a part of the writing process that does not require letters or words at all, but simply visualization of ideas upon the page.

As I worked on this codex in Oxford last summer, examining each page’s text and annotations, I turned a leaf to discover… a dragon! Unbeknownst to me until I turned that page, in the lower margin of a page in the section on medical remedies, someone had drawn in a dragon. It would take much more study and many more words for me to suggest why it is there, when it was added, or how it might relate to the text. However, I’ll posit here that this drawing of a dragon—made by a user of this book at some point after the eleventh century, and perhaps around the same time as the Tremulous Hand in the thirteenth century—was itself a way of writing in one’s book. Simply its presence in a margin of Hatton 76 reveals the book’s value as a place to draw one’s ideas, to draw the dragon that a medieval artist—very likely also a medieval writer/scribe—found reason to sketch here in a text about medicinal remedies derived from, of all things, quadrupedal and bipedal animals such as dragons.

I hope that these examples of writing in Hatton 76 can serve as inspiration for writing in our books, and for encouraging writers that many of us work with in Writing Centers to write in their own books. I would encourage everyone to do more of their writing in books, free of the stress of the blank word processor page, to build ideas before or even alongside taking them to more conventional modes of drafting.

Just one caveat—the Worcester monks wrote in books from their library. Please only write in books from your personal library, not from actual institutional libraries. Librarians generally will not appreciate it, even if you draw a dragon.

For readers who would like to join the conversation—Do you write in your books? What do you write and where? Do you copy your notes out somewhere else? Or do you go straight into writing and illustrating your ideas in the margin of the book? Please share by leaving a comment!

Leah that is a wonderful piece. I have to say I have not written in a book, but I do write additional thoughts and comments in my draft(s) while working on a piece for publication. (as does my editor)

What a lovely piece of text on how we somehow physically connect with the past (and past writing). Thank you for it. My experience is similar to yours – I do write in my books (also in order to teach others), sometimes arguing with the text a little. Perhaps these days it is similar to how we add our comments or posts on the texts we’ve read on-line. (BTW, has anyone else commented on the dragon in Hatton 76?)