By Erica Kanesaka Kalnay

“I am not a painter, I am a poet.

Why? I think I would rather be

a painter, but I am not…”

— Frank O’Hara

In “Why I Am Not a Painter,” a famous ekphrastic poem by Frank O’Hara, the poet recalls drinking a few beers with the expressionist painter Michael Goldberg. As they drink, he watches Goldberg create a painting inspired by the word “sardines.” When the painting is finished, O’Hara observes that no sardines appear anywhere on the canvas. He goes home and writes a poem inspired by the color orange. The word “orange” does not appear anywhere in the

finished poem, either.

As a graduate student in Literary Studies, I spend most of my time tinkering around with words, but I am also an

amateur visual artist. Consequently, I sometimes think about “Why I Am Not a Painter” when I meet with the many talented art students who visit the Writing Center. As they tell me about their art, I tend to feel a mixture of amazement, puzzlement, jealousy, and inspiration. Their orientation toward their studies just seems so different from my own. These feelings are, I think, not unnatural, but integral to Writing Center work. Somewhat like the encounter between the poet and the painter that O’Hara depicts, Writing Center work involves crossing genres, media, and disciplines. These crossings—in which we must leave our “comfort zones”—ideally spark dialogues that invigorate the creative processes of both: writer and tutor, poet and painter.

The practice of ekphrasis rests on similar assumptions. From the Greek ἔκϕρασις, “ekphrasis” refers to the description of a work of visual art in a literary form. Ekphrastic writing asserts that there’s something to be gained from thinking across disparate forms, from putting words to that which seems to resist them.

Description in the Writing Center

It occurs to me that a significant portion of Writing Center tutoring is, like ekphrasis, based in a practice of description, of speaking toward something. As writers, we try to find words for things that do not yet exist in language. To find these words, we often begin by describing what we think we “see”: whether it’s what we notice in a work of art—a painting, a poem, a novel—or what we notice in our research. We look for links, patterns, particulars, shapes, and gaps. And then we attempt to describe them.

For instance, a typical Writing Center session might begin like this:

- The writer describes the task or problem they’re facing.

- The writer describes the object(s) of analysis: the text, the experimental data, etc.

- The writer describes the rough idea or argument (as distinct from actually making an argument).

- The writer describes the challenges of presenting that idea or argument.

- The writer describes the goals for the session.

It’s easy for these moments of description to start to feel routine. However, I find in my own experiences visiting the Writing Center that they are, in fact, extremely productive. In describing my writing and my writing process, I begin to articulate ideas that I only half-understood before someone asked me to talk about them. In this way, description can provide us with a starting point for the writing process, particularly when we’re trying to speak across gaps—between hunch and idea, between writer and tutor, between one discipline and another.

Descriptive Pedagogies

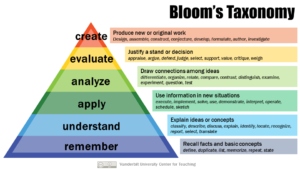

One reason I like “description” is that it feels unintimidating in comparison to terms like “analysis,” “critique,” or “argument.” As a Writing Center tutor, I can ask writers to describe their work, and they will usually answer with confidence, rattling off the plot of Oryx and Crake or the parts of a hydraulic motor. In contrast, when I ask writers to analyze, critique, or argue, they become much more likely to hesitate. We are told that these latter terms require more complex thinking, and that pushing students toward these higher orders is important, particularly at the university level. On Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives, analysis, critique, and argument are typically found toward the top of the pyramid, while description falls near the bottom (see figure).

And yet, even the process of creation, a cognitive domain usually placed at the very top, can start with something as simple as “sardines.” Ekphrastic writing is based on the premise that description does not merely create a copy of the original, but enlivens what it observes, making something new in the process. In attempting to describe something, we come to see it more clearly—or even to see it afresh.

Descriptive Scholarship

But can the writing we produce in universities ever be understood as itself descriptive? The anthropologist Clifford Geertz notes that description can assume a variety of shapes, densities, and textures, not only in a poem or story, but in scholarly writing. Geertz coins the term “thick description” to refer to a descriptive mode that acknowledges how signs are interwoven within larger systems of signs. For example, a wink might be described simply as the closing and opening of a single eye. However, this thin description cannot fully convey a wink’s social and cultural meanings. Rather, an anthropologist’s description of a wink must place it within “a stratified hierarchy of meaningful structure in terms of which twitches, winks, fake-winks, parodies, rehearsals of parodies are produced, perceived, and interpreted” (7). In other words, we need to understand the context within which that wink occurs—its coordinates in space and time and its relationship to other signs that might not be immediately visible.

More recently, in my own discipline of literary studies, scholars have likewise been debating the value of descriptive methods. The “descriptive turn” calls attention to the surface of the text, refuting the idea that literary criticism must work to uncover hidden ideologies. Many of these debates draw from the work of the sociologist Bruno Latour, who writes that scholarship should seek “to describe, to be attentive to the concrete state of affairs, to find the uniquely adequate account of a given situation” (144). Unlike Geertz, Latour wants to do away with context altogether. For him, boxing an object of analysis into a given context is simply “a way of stopping the description when you are tired or too lazy to go on” (148). However, whether we see description as an end in itself, or just one of many modes that writers might assume, description can be a helpful place to start.

Description and the Artist’s Statement

The importance of description to Writing Center tutoring became particularly apparent to me when I began working with visual artists. An M.F.A. student in 4D Media came in for an appointment one day and asked for help writing her artist’s statement. She pulled a pile of crumpled papers out of her backpack. On them were sketches and photographs of her work. She had designed a series of tents. Each tent opened up into a magical, surreal world. In one, everything was covered in pink faux fur. In another, everything assumed a polished, white surface.

“I don’t like writing,” she admitted. She explained that words did not come naturally to her and that she communicated better in material language. This was part of what had drawn her to art in the first place. Now she was being required to produce a piece of writing that would force the multisensory dimensions of her chosen media into a language that simply didn’t fit.

I could see where she was coming from. The artist’s statement can be a difficult genre. It carries many of the burdens of the personal statement—for example, the awkwardness of self-presentation—with additional challenges specific to writing about art. Not only do words fail to perfectly convey images, but we often assume that art should “speak for itself.” Then, paradoxically, we ask the artist to explain it to us.

After the session, I researched the advice typically dispensed about artist’s statements. Mostly, I came up with a long list of don’ts: Don’t sound grandiose. Don’t resort to clichés. Don’t compare yourself to other artists. Don’t quote Deleuze. Don’t use “International Art English” (Rule). (The art world’s own distinct version of academic jargon that favors words like “aporia” and “traverse.”) While these don’ts offer a useful caution against pretentiousness, I could see why they might be paralyzing. An art student might be left wondering, “What can an artist’s statement do?”

Well, several things. On a practical level, the artist’s statement serves largely unavoidable institutional interests. Schools, galleries, museums, residencies, awards, and other institutions all require artists to write about their art. However, as a museumgoer, I might also add that I enjoy reading artist’s statements, and I find that they in no way detract from the aesthetic pleasure I take in viewing the art itself. Institutional imperatives aside, contemporary art has moved toward an aesthetic in which we now expect artist’s statements to serve as complements to art—for better or worse. So, instead of getting caught up in don’ts, we might note that, at its most basic level, the genre asks artists to begin by describing. This “thick description” ideally enriches and expands our understanding of how works of art take shape within larger contexts.

Consequently, Sarah Eldridge, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, teaches her M.F.A. students to reframe the “artist’s statement” as an “art statement” (Garrett-Petts). Intentionality is bracketed off (“what did I try to do?”) and replaced with a practice of attentive observation (“what do I see?”). Instead of interpreting or analyzing the art, the artist looks at it again and describes it.

Toward Ekphrastic Tutoring Methods

Because the Writing Center offers the benefit of an outside eye, it affords an ideal space for artists to practice ekphrastic skills. In addition to borrowing from many of the tools and techniques we use to teach personal statements, Writing Center pedagogies might therefore also begin to explore tools and techniques best adapted to the creative disciplines.

In my own limited experience, I’ve found that working with artists at the Writing Center has stretched my tutoring methods. For example, I love how artists draw as they describe their work to me, even when I haven’t explicitly asked them to do this. They’ll often stop mid-sentence and pull out a pencil and sketchbook. (Engineering students do this, too.) Whenever this happens, I’m forced to realize that I tend to privilege talk-based strategies. The need of artists to draw will remind me that there are other possibilities: outlining, diagramming, rereading, researching, free writing, and so forth.

An M.F.A. student once showed up to one of our ongoing sessions with a magazine she had designed. She wanted to create an insert that would offer readers suggestions for alterative uses to which the magazine could be put. The magazine was not only meant to be read, but flipped, cut, pasted, folded, and reworked. As she described all of this to me, I came to see that my fallback Writing Center tutoring strategies were inadequate to her particular task. But there was also something exciting about encountering a problem unlike any I’d seen before. When I went home to write that evening, I saw my own work a little differently, too.

For further resources and reflections on creative approaches to Writing Center tutoring, you may be interested in: Sarah Dimick’s post on the intersections between creative writing and Writing Center pedagogies, Adedoyin Ogunfeyimi’s post on storytelling in the Writing Center, or a previous post of mine on the Writing Center and childhood play. Those interested in visualization in Writing Center tutoring may also wish to explore Jessie Reeder’s post on this topic.

Finally, please share your thoughts in the comments. How do you use “description” in your writing and tutoring practices? Have you tutored writers working on artist’s statements? What are the affordances and challenges of this genre? What methods do you think work best for tutoring artists?

________

Works Cited

“ekphrasis, n.” OED Online. Oxford University Press, June 2017. Web. 9 July 2017.

Garrett-Petts, W.F. and Rachel Nash. “Re-visioning the Visual: Making Artistic Inquiry Visible.” Rhizomes, no. 18, 2008. Accessed 9 July 2017.

Geertz, Clifford. The Interpretation of Cultures. Basic Books, 1977.

Jordan, June. Who Look at Me. Crowell, 1969.

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford UP, 2005.

O’Hara, Frank. Selected Poems. Knopf, 2009.

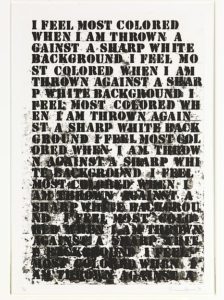

Rankine, Claudia. Citizen: An American Lyric. Graywolf, 2014.

Rule, Alix and David Levine. “International Art English.” Triple Canopy, no. 16, 2012, Accessed 9 July 2017.

Ruskin, John. Modern Painters. Vol. 5, John B. Alden, 1885.

-

イオタι[iota]

iota

Thanks for this insightful post, Erica! I particularly appreciate the way you recuperate the value of description–it often gets pushed aside in favor of argument or analysis, but it’s such an important part of academic writing. This post reminded me that most of my favorite essays open with description–a sort of “lay of the land” section that helps orient a reader–and this feels like a generous way to draw a reader in.

I’m inspired to criticize my own limited approach to pedagogy through Erica’s nuanced and obviously thoughtful reflection on writing instruction and ekphrasis. As someone who is both trained in the visual arts and literary studies I’ve always struggle to connect these two passions with their varied methods.

When I’m creating a paper, object, idea, etc. I engage myself as an active observer of the outside world, free draw, free write, talk to a friend about it, walk aimlessly, and even read texts differing from my subject. But, I don’t teach this way. When I teach topic development and writing I bring out the classic worksheet model and expect them to silently and abstractly develop detailed brilliance. How silly of me. I’m interested to consider deeper how to develop and evaluate transdisciplinary approaches to teaching writing.

This is a fascinating post, Erica. It was interesting to see how you reframe a literary practice as a pedagogical model here. My own experience with ekphrastic representation has been working with a scriptwriter, who was creating a verbal description of the work she hoped to produce (so that the actual production of the visual art hinges upon the persuasive ekphrastic portrayal). I had not considered my work with such students in terms of a pedagogical ekphrasis, but that seems to very appropriately frame the sort of co-envisioning process that was required. Upon reflection those appointments depended upon a dialogic ekphrasis in which each of us had to describe the scene which was taking place in our heads based upon the current script. It was interesting since in that situation the ekphrasis is actually dynamic, since each of us was describing their vision of the potential object to other which often reshaped the corresponding description. This shakes up my traditional view of ekphrasis as a very stable and object-oriented practice. I’ll have to consider this further.

I love how you portray the different uses of description here and how it can reorient our view of a text. It challenges the way we prioritize other modes of thinking and helps me consider how I might usefully dwell longer in description. I’m already thinking about different ways I ask students to describe their projects and how I might use this more purposefully in teaching. Thanks, Erica!

Thanks for writing this blog post, Erica! This past spring and summer I participated in a public art project called Art En Route. Madison community literary writers collaborate with artists two pieces of art that says something about the city. The final pieces will go on Madison’s buses starting this Fall. For next week’s open reception, my artist and I had to write an artist statement; I had never written an artist statement before, so searching for genre conventions and advice online revealed much of the same advice you describe in your post.

I settled on describing the concept we were going for–the ambiguity and uncertainty of racial, gender, and sexual identities and the issues those identities can lead to. Then I explained how my one-word “small fates” tried to play out that concept, and my artist explained how her art played out that concept. So we ended up describing what kind of action the art should take, would kind of work it should do in the Madison community; not physical work, but emotional labor. After I turned the statement, I thought nothing else about it-; we had written the statement under a tight deadline, and, of course, I had to move on to the much longer dissertation. But reading your post makes me think I need to return to the artist’s statement helped craft and really think about how I was using ekphrasis. I might turn the act of using this concept for my writing into my tutoring. I think it might help other writing tutors to collaborate with an artist and then write a statement with them; then reflect back on the experience of “dancing about architecture.” Could be a generative and rewarding experience.

Erika, thank you for this thoughtful and thought-provoking post! I was struck by what you said about “description” being a less intimidating request than “analysis,” and other critical work we ask of our students. Without realizing it, I believe I frequently get myself working on my dissertation by starting with description: what’s going on with a word, a line of poetry, or a manuscript. From there I often latch onto something interesting that spirals into analysis, but the kernel of description is usually where that gets started, even if the descriptive text later gets shortened or cut in revision. I’ve made this recommendation to art history students before, to just start by describing the object, but I want to think more about how this might be helpful for writers in other fields, to explicitly invite description as the foundation for writing and revision.

Very lovely post, Erica! A question that I had when I finished (re)reading your essay was whether the ekphrastic pieces (stages?) of the writing process are ultimately erased in the finished product. I think your observation that writers come into their appointments describing their work is right on, and the way that you leverage that observation to reflect on your tutoring work and potential ekphrastic methods is inspiring and helpful. But does this all go away in a later stage of the writer’s paper–when the writer is no longer describing the project but performing it? That question is probably over-simplifying, but I appreciate how your post is making me question the role of ekphrasis in my own writing as much as it makes me question the role of ekphrasis in my writing process.

Thanks for this fascinating post, Erica! What you say about the value of description really resonates with my own attempts to work through my dissertation in the Writing Center. Trying to describe my project and why it’s interesting often helps me find the gaps in my writing when I’m having trouble getting enough distance to critique my work.

You’ve made me also think about the value of description in instructor responses to student writing. I wonder how we can think about instructor description of the reading experience (i.e., “I got really excited by your introduction but I kind of lost track of your argument in paragraph 5”) fitting into this pedagogical approach. I’m not sure if they’re related, or if I’m comparing apples and oranges (or sardines and oranges?) but you’ve made me think about my teaching differently!