By Antonio Tang –

My name is Antonio Tang, a sleep-deprived father of an 8-month-old, a PhD candidate in composition and rhetoric scheduled to finish this fall, and this year’s summer director of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Writing Center. Keeping all these balls in the air has been difficult, and this director’s role represents the first official leadership position I have taken on in graduate school. That is not to say that I am not familiar with the mission and best practices of our Writing Center; I have spent many years tutoring at the main center and at two libraries on campus (Brad Hughes, the Writing Center Director, likes to say that I have “tenure”), and I have actively participated in many professional development activities. But the shift from being a writing tutor to an administrator is a categorically significant one and marks a transition within a larger transition for my newly expanded family. For those considering taking on a similar role, I invite you to ponder the joys and challenges of becoming a writing program administrator and consider some observations and strategies. I hope these lessons will also prove helpful for those who are mentoring others in such a position.

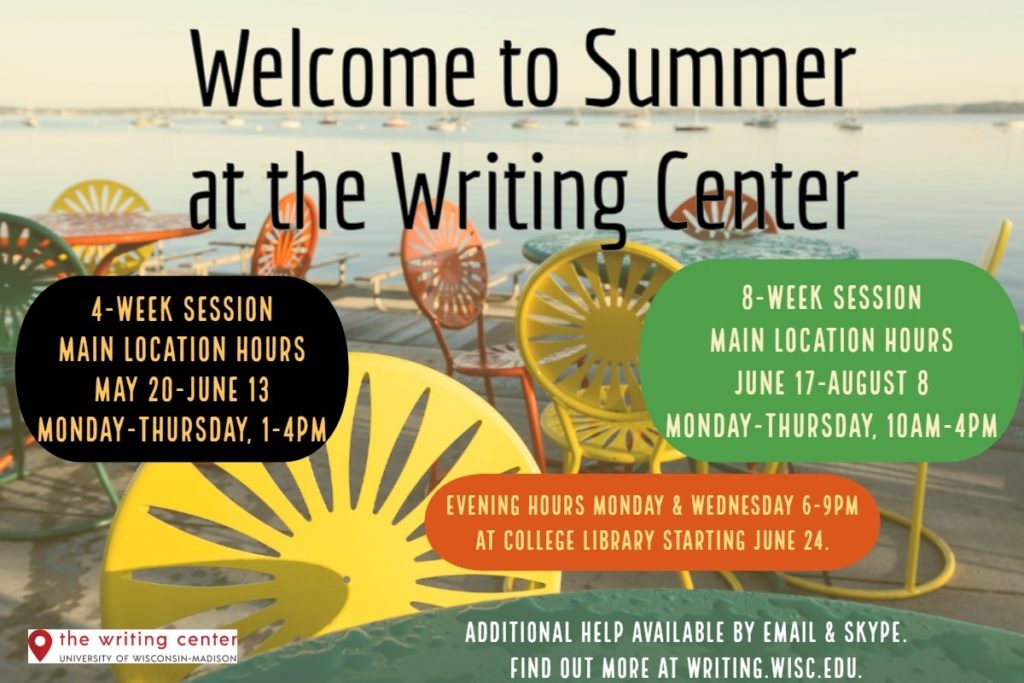

There’s a great satisfaction in seeing a puzzle come together. Let me briefly describe my job. Although our two summer sessions run from May 20 through August 8, I headed the tutor selection and hiring process that began the end of March. Altogether, with help from staff, we brought together 17 experienced tutors from disciplines as varied as English, Curriculum & Instruction, Linguistics, and Law. Selecting and scheduling tutors, assigning roles, and developing workshops took most of April and May, and I am happy to say that we have been able to offer seven workshops on academic and employment genres, a writer’s retreat, two graduate writing groups, evening satellite hours at our university’s undergraduate library, and limited hours for email drafts and Skype requests. In addition, we are fielding a three-person outreach team that is coordinating and organizing over a dozen co-teaching and orientation engagements with students from Education, Soil Science, and Engineering among other fields. On a microscopic level, in my role of summer director, I oversee the smooth-running of these activities, ensuring that we stay within our budget and that all tutors get the support they need. On a broader and more intimidating level, I am supporting a campus of student writers in their intellectual pursuits and fostering a strong writing culture. Such a task would be impossible without generous support from Jen Fandel, our Writing Center Administrator, and regular weekly conversations with Brad Hughes, the Director of the Writing Center Director and the Director of Writing Across the Curriculum at UW-Madison. The professionalism of our receptionists–Farid, Jenna, and Lisa–has been inspirational, and it was my pleasure to get to know their interests and academic goals and to jump in and help them in a pinch.

Part of the inspiration for this post came from Margaret Mika and Daniel Harrigan’s story of hiring an assistant coordinator for the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Writing Center. What struck me about that April 2017 blog post was how closely Daniel’s transformation from a Writing Fellow and tutor to a full-time writing program administrator mirrors my own. Like him, being tapped for an administrative role induced an initial nervousness; I know little about administration beyond what I have read, written, and studied about the subject. It was timely that I had participated in Brad’s five-part Writing Center and WAC Leadership Discussion Series earlier this past spring; the readings and conversations contextualized my doings and reminded me that leading a writing center goes beyond caring for the logistical aspects but considers larger institutional concerns that involve economics, allies, and values. Unlike Daniel, though, who went in eager to take on any task–“I felt that I could perform them all”–my emotions have been more subdued; I am gingerly feeling my way around, with each small success–a finished email, a friendly chat with a tutor, a compliment on an orientation meeting run well–building my sense of belonging. But there are several strategies and perspective-shifts that have eased this transformation, and I want to turn to them next.

Understanding Administrative Work as a Form of Teaching.

I’m taking a literal page from Brian Jackson, who argues in “Watching Other People Teach: The Challenge of Classroom Observations” that the practice of instructor observation can be considered “macro teaching” or “the process by which a WPA’s approach to writing education will be felt at the delivery point (i.e., the single student)” (editor Amy E. Dayton, Assessing the Teaching of Writing, Utah State UP, p. 48). Writing Center work thrives on the creation, retention, and multiplication of delivery points. That is to say, we interface with students in all aspects of our instruction, from outreach activities and in-house workshops to individualized tutoring sessions, and any administrative decision has a direct bearing on the number and kinds of students who use and continue to use our services. To take an example, at the suggestion of last year’s summer director, I made a conscious decision to reserve some off-schedule hours for student writers referred by our disability resource center. Not every student is able to make our shortened summer operating schedule, so it was heartening to be able to serve students grateful for this extra flexibility. Another choice I made–to be physically present in the main center for the majority of my day–gives me more opportunities to greet students, answer visitor questions, and interact with tutors before and after a session, a posture that brings me closer to that delivery point and has made me feel more connected with the goings-on of our center. In my conversations with tutors on their sessions and their feedback to email drafts, I can help shape how instruction is given. Being a writing instructor for so many years also allows me to empathize with the responsibilities tied to tutoring writing. I can choose to be a tutor’s advocate, turning off the main center’s lights a little later so that records can be done promptly and thoroughly. Well-written records allow milestones and writing concerns of a particular student be more easily grasped and incorporated into a session by subsequent tutors.

Being Kind and Gracious.

While it may seem trite to discuss the advantages of civility in administrative work, I’d like to reframe the adoption of a caring and gracious ethos as an adjustment strategy for greenhorns like myself. I find that people in general respond in kind: Exuding grace (generosity) helps shapes an environment that is more patient and forgiving toward mistakes and oversights, things that a newbie will undoubtedly commit. In emails to tutors, I err on the side of personability, favoring “I” over the royal “we,” being generous with praise, and adopting an informal yet respectful register. At orientation, tutors and I discussed ways of caring for student writers deeply and broadly beyond their drafts. In those meetings, I also confessed my inexperience in a directing role (and in the same breath, my comparatively extensive experience as an instructor) and stressed my openness to correction and improvement. I intentionally modeled a welcoming and relaxed ethos with visitors and affirm receptionists who do the same. As a new director, I have learned to not only be a dispenser of information but go that extra mile and actively connect people to those resources. So far, my colleagues have not hesitated to approach me when they detect a problem, knowing that they will not be reproached and that I take will them seriously. A gracious ethos is more than an attitude; it levels the path for any first-time directing effort and is instrumental to creating that larger vision of care that attracts student writers.

Experimenting as an “Outsider.”

The smaller scale of the summer Writing Center partly enables this, but the lack of prior administrative experience can be an opportunity for examining existing inadequacies through fresh eyes and for inventing new solutions for them. At the UW-Madison Writing Center, tutors, students, and assistant directors have been seeking to improve our method for keeping track of ongoing students (i.e., students who desire to work with the same tutor over a long writing project or a series of shorter assignments), and discussions among the spring 2019 leadership team resulted in a more structured mentorship system that the summer Writing Center is currently piloting. I have enjoyed the challenge of thinking through this new system, writing the documentation surrounding it, and generating buy-in from tutors and student writers. A few weeks into our eight-week summer session, in an effort to increase foot traffic among undergraduates, the Center also directly reached out to selected course instructors across the campus and offered to give five-minute overviews of our services. We embraced the positive response even though these visits had to be worked into our outreach team’s busy schedule. Because of my newcomer status, I am less paralyzed by the fear of breaking something and more motivated by the thrill of possibly finding a solution. In “Trickster at Your Table,” a chapter in The Everyday Writing Center: A Community of Practice, Anne Ellen Geller et al. illustrate that embracing “play” opens our eyes to unconventional but equally effective ways of doing writing instruction, but I venture it comes easier for someone who is new to the position. And lest I be lost romping in the fens and spinneys (a Frasier reference!), what keeps me grounded is being in constant communication with others who had taken on the same position, letting their knowledge inform but not stifle my own creativity.

Dabbling is another aspect of play, and it has been a joy for me to be involved in almost every aspect of Writing Center work: participating in outreach planning meetings, crunching budgetary and staffing numbers, approving ads, thinking through our online handbook, explaining what we do to main center visitors, listening to a workshop instructor’s debriefing, and extolling the motivating value of stickers to my graduate writing group. For one seeking familiarity with a position, it helps to embrace that omnipresence even when it doesn’t come with any omniscience–and especially when it doesn’t. Seeing all these operations sustains my humility and teaches me how simultaneously small and large a director’s role is. It remains large in that, while it may not call for a heavy involvement in any one thing, it demands an astuteness and curiosity toward all things. “Playing” involves being flexible too, such as when a parent of a prospective student walks into the main center five minutes after closing and wanting to know about the procedure to make an appointment.

I would have never considered being a summer Writing Center director had Brad Hughes not offered the position and Mia Alafaireet, the outgoing assistant director for 2018-19, not insisted that I accept it. My son Westley was only a few months old, and I was barely hanging on to sleep and sanity as it were. Trying to get a feel for the workload and responsibilities, I began bombarding last year’s summer director with early morning and late afternoon texts and calls. What these figures saw, presumably, was my potential as a director in the thick of my preoccupations. Nicole Caswell et al.’s The Working Lives of New Writing Center Directors classifies investing in tutors’ lives and growth as part of the emotional labor of directors. I am grateful that Brad, Mia, and Annika Konrad take that labor seriously as I had difficulty seeing through the temporary upheaval in my family to my own leadership potential and a chance for professional growth. And now, having been in this role since March, I’m starting to feel like I could do this and that I am a valuable and valued addition to the Writing Center team. The familiar buzz of talk and typing is assurance that our good work continues unabated.

Photo Credits

Featured image of butterfly, by Doug Kelley on Unsplash.

Puzzle pieces, by Hans-Peter Gauster on Unsplash.

Carousel, by Levi Damasceno from Pexels.

Antonio, I was especially struck by your comment about exuding a spirit of generosity. I think that you do this well, and I think that it serves all of us alike–staff, instructors, students–to keep this spirit at the forefront. We’re all still learning and trying to improve, and thankfully universities honor and nurture that spirit (often a bit more than traditional workplaces). Thanks for reminding us to keep up that spirit!