By Melisa Mansuroglu, University of Connecticut

During the summer of 2023, my director at the University of Connecticut writing center, Tom Deans, presented me with the opportunity to extend a project that he helped create while a Fulbright Scholar at Uganda Christian University (UCU) in 2021-22 (Deans). Tom’s goal was to help UCU establish a writing center as the centerpiece of his scholarship to enhance students’ writing skills and peer collaboration. When Tom told me more about UCU’s inclination to continue working with UConn, I was so excited about the chance to be a part of it. My own experience as both a writing tutor at the University of Connecticut’s writing center was transformative and showed me the impact such spaces can have on fostering growth, confidence, and community among writers, and I wanted to help bring that same opportunity to students at UCU. For the next 10 months, I worked on facilitating regular, online tutor-to-tutor meetings between students at UConn and UCU (or really tutor-to-coach since UCU calls their student staff writing coaches). What I didn’t expect was the difficulty of working across cultures.

Uganda is eight time zones ahead of the US. As a very type-A kind of person, I am all about schedules and strict time frames. When scheduling these online video chats between UConn’s tutors and UCU’s writing coaches, aligning the time zones was hard, and getting speedy WhatsApp responses even harder. I tried to stay positive but got frustrated when several meetings were missed and I had to reschedule them. I shared my frustrations with Tom and we discussed the factors likely playing into the situation: that UCU’s coaches are unpaid, that they didn’t always have robust internet and cellular connectivity, and that they, like our tutors, are busy with multiple commitments. I also learned the notion of “African time,” a term that Westerners often use pejoratively to explain tardiness in life events that are characterized by others as important, but that we might think of instead as a cultural tendency that relies on a more relaxed attitude towards time. As I dove into this concept further, I noticed that it often unfairly stereotypes Africans as being careless about schedules.

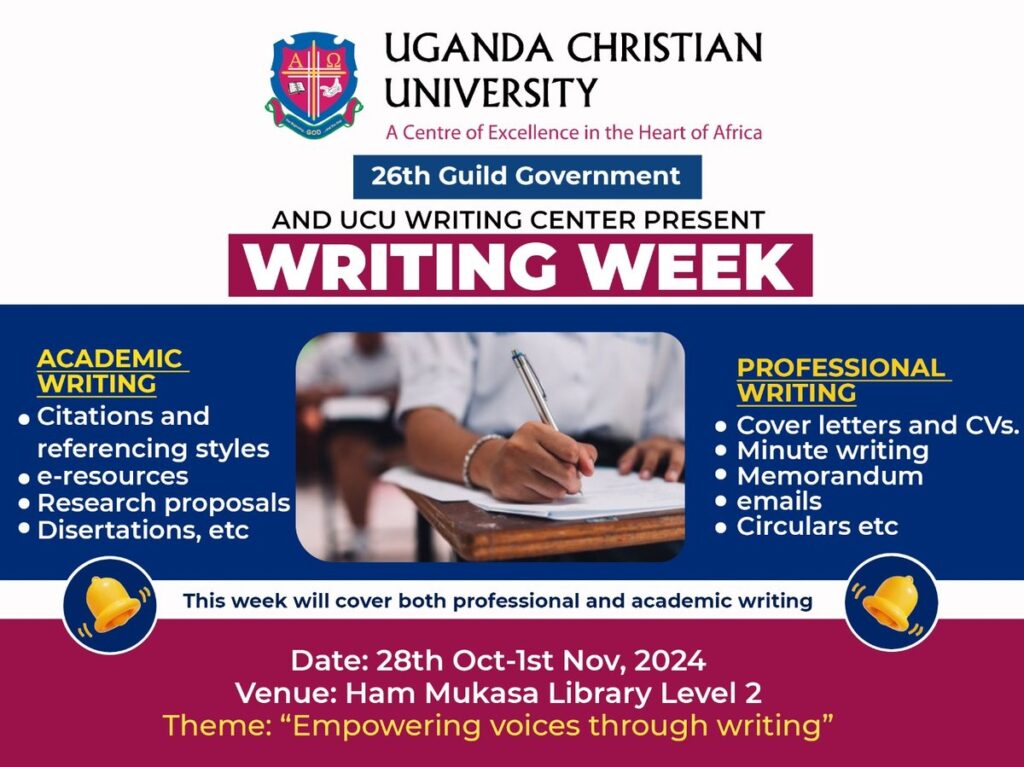

Although how the Ugandans handled time didn’t necessarily abide by my very clock-centric sense of time, I started to notice that even if things weren’t getting done exactly when I thought they should, they still got done. I started to get a little more at ease with a fluid notion of progress. I have learned a lot from the Ugandans, but one of the biggest things is that progress and productivity can be achieved in many different ways. For example, while I was puzzled as to why I was having such a difficult time setting up meetings, I soon came to find that I was not getting replies because the UCU Writing Centre was hosting its first-ever “Writing Week.” This was a week where the coaches and faculty created a bunch of different promotions for their center and went to various lectures to speak and increase the campus awareness of the Writing Centre. I realized that just because the process I am comfortable using did not happen does not mean that productivity is not in motion. “African time” should not be seen as a lack of commitment or understanding of time or future planning.

I’ve come to realize that it instead reflects a cultural approach to time that prioritizes events and relationships over strict adherence to schedules—the very concept very similar to what Anne Ellen Geller explores in “Tick-Tock, Next: Finding Epochal Time in the Writing Center.” Gellar focuses on the tension between clock time and epochal time in writing centers and during tutoring sessions. She defines “epochal time” as a notion of time that is characterized by events rather than fixed intervals and can lead to more fulfilling tutoring experiences for both tutors and students. She describes instances when tutors shift their focus away from the ticking clock to engage more deeply with students and their writing projects, which often fosters a more productive and satisfying learning environment.

I learned to value different aspects of time, which made me more curious than ever to learn about the dynamics and how the UCU Writing Centre held its sessions. I spoke with Martin Kajubi, Acting Manager of UCU’s Writing Centre, over a Zoom call—which we had to reschedule a few times!—but we eventually found the time. I wanted to learn how UCU’s center uses time. I asked him: Are there session time limits? How do the appointments work? How do your sessions run? Kajubi informed me that they do run on an appointment basis, stopping and starting the sessions at their respective slots, which vary. He explained that one of the responsibilities of their coaches is to analyze each session beforehand and determine whether or not they think they will be able to fully help the students in the time that they have. I couldn’t get him to articulate specific session time spans, which in and of itself tell us something. This, to me, is already utilizing epochal time in the sense of valuing the actual content and experience of the session, versus focusing on the restrictions of time before all else.

I think the most significant thing I took away from my call with Martin was what I needed to hear throughout my entire time with this collaboration: time is more fluid than my clock-bound notions of it. I learned that we taught them a new way of viewing time, too. Martin said, “I pray this collaboration stays for a long time and allows our center to keep growing. I am grateful to the UConn Writing Center… Our coaches get stronger every day by getting advice about how we can best help our students with the time and resources we have available.” He further emphasized that they learned a new sense of time from us, adopting new strategies from speaking with our tutors on how to work in 20-30 minute blocks and have the writers leave happy. This is what I see to be the importance of international collaboration.

But of course, international collaborations are ethically complex, which hit home for me after a month or two when I read the Writing Center Journal article, “Writing Centers and Neocolonialism: How Writing Centers Are Being Commodified and Exported as U.S. Neocolonial Tools,” in which Brian Hotson and Stevie Bell critique the origins and dynamics of the very kinds of activity I’m describing. Reading their commentary made me realize that I may have been a bit naive to the potential imperialist and neocolonial forces at work when Western nations, and especially the US, seek out collaborations. This was my first time understanding that international initiatives can unknowingly spread Western education and ideology in ways that align with neocolonial practices.

Is that what is happening in the UConn/UCU coach-to-tutor encounters? I see both sides of the argument, but I have also witnessed the two-way learning through these connections. On one hand, the collaboration could be seen as neocolonial, potentially imposing Western practices and privileging UConn’s approaches. On the other hand, I’ve witnessed a genuine exchange of ideas, with UConn tutors learning from UCU coaches’ emphasis on relationship-building and adaptability, demonstrating a mutual reshaping of perspectives rather than a one-sided dynamic. In addition to gaining a more flexible understanding of time, UConn tutors learned valuable approaches from UCU coaches about forming personal connections during writing sessions. Martin shared that UCU coaches prioritize starting their sessions by getting to know the writers on a more personal level, which helps establish trust and openness before diving into the writing itself. This approach inspired several UConn tutors to reflect on the importance of tailoring sessions to individual needs, rather than solely focusing on the work at hand.

International collaboration is not about having one institution model what a perfect “writing center” is. It is the notion of reshaping our mutual cultural views and sometimes narrow values to learn from one another. Given Hotson and Bell’s article, to avoid falling into neocolonial practices, it’s essential to approach these collaborations with humility and an emphasis on reciprocity, ensuring that both institutions have equal influence in shaping the direction of the partnership.

What started as a frustration with scheduling for me became a lesson on how to not be so obsessed with my Americanized version of time, to experience more than one kind of productivity, and to appreciate epochal time. Of course, there are many aspects of my daily life that I have to abide by time with, that is inevitable. However, this collaboration with UCU has been an amazing experience where time didn’t have to be so central. When I started my work with UCU, I already subconsciously had preset deadlines I’d have for this project before I even started anything. Throughout my time working with the UCU folks, I’ve learned that working across time zones is about more than setting schedules and expecting everything to work out the first time.

Works Cited

Deans, Tom. “Toward a Writing Center in Uganda: The Proposal Stage.” Connecting Writing Centers Across Borders, 17 Dec. 2021.

Geller, Anne Ellen. “Tick-Tock, Next: Finding Epochal Time in the Writing Center.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 25, no. 1, 2005, pp. 5–24.

Hotson, Brian, and Stevie Bell. “Writing Centers and Neocolonialism: How Writing Centers Are Being Commodified and Exported as U.S. Neocolonial Tools.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 41, no. 3, 2023, pp. 107–32.

Kajubi, Martin. “Uganda Christian University’s Writing Center Now a Year Old!” Connecting Writing Centers Across Borders, 12 Oct. 2023.

Melisa Mansuroglu is a 2024 University of Connecticut graduate who served as a writing tutor during their undergraduate years. During this time, she cherished the privilege of working with and learning from a diverse range of individuals, deepening her passion for advocacy and collaboration. Melisa currently works as an immigration paralegal in Boston and is set to begin law school in the fall of 2025 to further her legal career. You can find her on LinkedIn and Instagram (@melisa_mansuroglu).