By Lucy McInerney and Jenna Morton-Aiken, Brown University

If you were to walk into the Writing Fellows training classroom at Brown University at three minutes past 1:00 p.m. on any given Tuesday, you would find a darkened room littered with the bodies of students in repose. As you blinked down in confusion at the student closest to you, her head propped on her backpack, and her neighbor seated and leaning against the wall, you would hear the quiet and warm voice of a young woman coming from a speaker at the front of the room.

“May you love yourself as you are,” the voice intones gently. This is Dora Kamau, one of the meditation teachers on the Headspace app and unofficial but integral co-instructor of our course. Her voice pauses, allowing space to breathe in and out again mindfully. “May you accept yourself as you are.” Around our classroom, air whooshes gently through noses and out of mouths as Dora’s voice completes the verbal triptych that anchors every session. “May you live at ease with who you are.”

Why Mindfulness in Writing Fellows Training

As you might imagine, weekly dedicated time to meditation and reflective writing was not included in the original syllabus for ENGL 1190M, The Teaching and Practice of Writing: The Writing Fellows Program. Founded by Dr. Tori Haring-Smith at Brown University in 1982, the Writing Fellows Program was first conceived of as a response to concerns about the quality of college writing and writing instruction across campus (Haring-Smith, 1992). Today, the Writing Fellows Program continues to play a critical role in the teaching of writing at Brown, particularly with Brown’s ongoing commitment to Diversity and Inclusion. Last semester, the program flipped its application process to promote greater diversity in its student makeup. Previously, students had to self-select as Writing Fellows by filling out a rigorous application, taking 1190M only if their applications were accepted. Now, students of any year and any background can take 1190M without applying first to be a Writing Fellow. About half way through the semester we open up a very simple application, so that the students who apply are already well trained in the antiracist writing pedagogy of the course.

This very simple change has effectively grown our cohorts into a more diverse pool across disciplines as well as across demographics, with students who might not otherwise have been confident enough in their “editing” skills to apply for the program now taking the class and realizing how well suited they are for the process of “fellowing.” The students who self-select to become Fellows by taking this class are highly motivated and typically already engaged with the process of writing, even if they were lacking confidence as “editors.” After a semester of training, these peer writing tutors are embedded in writing intensive classes across disciplines to support faculty in responding to student writing. Fellows are responsible for up to a cumulative 100 pages of student writing per semester, fellowing up to six students for a course with three paper cycles, up to nine for a course with two paper cycles.

Though these students are excited about writing and taking on the work of fellowing, they are also typically already balancing demanding course loads, campus jobs, and tightly scheduled social commitments. Knowing this, incoming Senior Associate Director for Writing and English Language Support for the Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, Dr. Morton-Aiken began the role intentionally considering avenues to support emotional health alongside more official Fellows training. She had found scaffolded reflective activities to be invaluable in the teaching of writing during her time as Assistant Professor at Massachusetts Maritime Academy (MMA), an approach that became even more critical as the Covid-19 pandemic unfolded. Though the populations differed greatly between the two institutions, she suspected the writerly gains made by MMA students would be equally effective in both writing and fellowing at Brown. Perhaps risky in her first semester teaching in the position, she chose a weekly ten minute Headspace meditation as the vehicle to integrate that habitual reflective space, hoping it would give them the cognitive space to attend to their positionality as writers as well as their mental and emotional health as individuals.

While we share below some of the research that speaks to the neurological and physiological benefits of meditation, Dr. Morton-Aiken actually introduced the practice to the classroom based on her own efforts to battle burnout, personal and professional fatigue, and general overwhelm during and following the transition to online teaching for her students and her children at home (Morton-Aiken and DeVasto, 2022). While she hadn’t meditated before the pandemic, she found the practice nourished her own wellbeing and stabilized her capacity to care for her students and their writing. Writing Fellows are placed in a similar position to a writing professor, needing to respond to both the writer and the writing in a complex and simultaneous encounter, and Dr. Morton-Aiken intuited that her students too would benefit from such a practice as Fellows and as stressed humans.

Researchers such as Hari Sharma (2015) have gone further, examining previous studies on the correlation between meditation and its effects on the body, and grounding in science what many writers already believed, namely that writing and the health of the mind are intrinsically linked. Scholars like James Moffat (1982) and JoAnn Campbell (1994) wrote in the eighties and nineties about the potential rewards of building meditation into the writing process, and more recently writing center administrators like Nicole Emmelhainz (2020) and Erika Sphorer (2008) have shared their experiences with using meditation in tutor training courses, while Rachel Panton (2023) has spoken about using journaling in the classroom as a way to address her students’ well-being in a holistic manner. In retrospect, our decision to address our students’ anxieties directly through meditation was clearly in keeping with this long and constantly growing tradition of validating the vulnerabilities of student experience in the writing classroom.

The Experiment

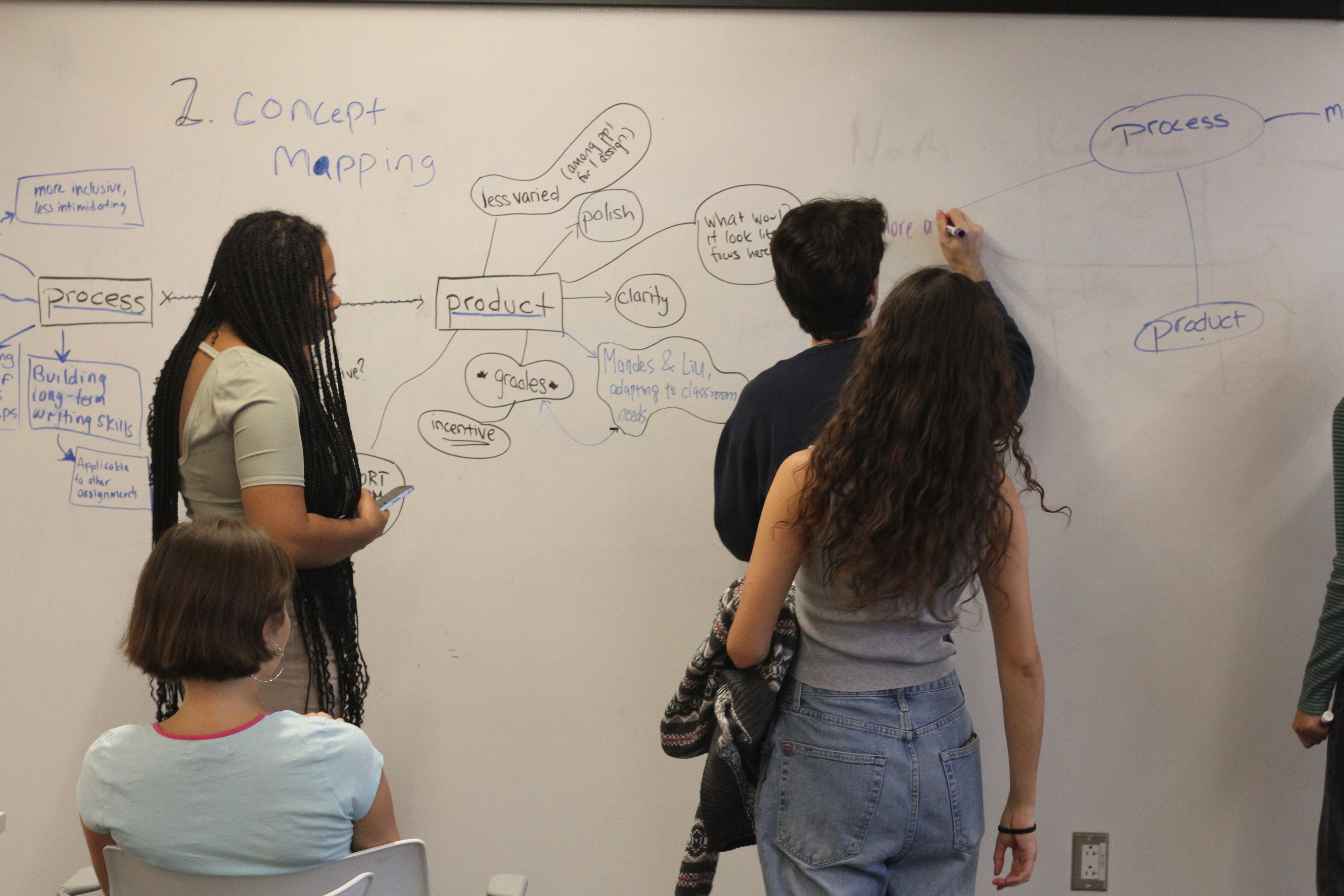

In the second full week of Fall 2023, we launched what would become our regular Tuesday practice: a ten minute guided session of Headspace’s “Self Compassion” course followed by five minutes of reflective writing and then an open invitation to share what that process felt like today. We dedicated equal time to freewrites on Thursdays, but that’s a different post. We did minimal framing for the first meditation, justifying it simply as part of our desire to center proactive mental well-being strategies in the classroom. We wondered initially if they would resist this invitation to take part in a mindfulness exercise every week. Would they find it uncomfortable (mentally or physically)? Would they object to losing a quarter of an hour with eyes closed and lights off when they could be working through our dense readings? Perhaps most terrifying, would they find our injunction to meditate somehow childish?

But even in our first few sessions, after letting the question breathe before moving onto the next activity, students began speaking. “It’s easier to give advice than follow your own,” offered one student, responding to Dora’s directive to be more compassionate towards oneself. “It was nice to have a moment to relax, I feel like I’ve been five minutes late all day,” admitted another. Another responded to the five-minute reflective writing that immediately followed, sharing that “she couldn’t not write about the thing she didn’t want to write about.” Our undergraduate TA seemed particularly excited to partake and experience how productive and generative meditation could be for the class as individuals and as a growing community.

Though somewhat apprehensive about the potential of raw honesty from our students, we shared out an optional and informal Google Form survey at mid-semester. About half the class responded, and their comments revealed that the meditation and free-writing was their favorite part of the class. When asked, “What was your reaction the first time we meditated in class?” responses varied, with some students expressing excitement or interest, some remembering a feeling of awkwardness. Many of them registered surprise at being asked to partake in a group meditation. These were all more or less reactions we expected, but it was heartening to see the degree of self-reflection our students were engaging in even at this stage. At least half of the responses displayed the type of metacognition that we spend so much time talking explicitly and implicitly about in the theory and practice of supporting writers.

In the same survey, we asked “Has your opinion of meditation changed over the course of the semester? If so, how?” The overall feelings seemed to be positive, with one respondent reporting that they benefited most days even if the sessions occasionally felt “cheesy.” Most of the responses expressed a sense of the cumulative effect of practicing meditation, reflecting on the exercise as a muscle that gets stronger with more use, as well as an attunement to the closely tied relationship between meditation, mindfulness, content, practice and the creation of community. We instructors saw this manifest in discussions in class and online as they increasingly reflected on how their lived experiences inescapably influenced how they used and gave feedback on language and writing.

Finally the survey also asked, “Has the practice of meditation or free-writing in 1190M had any effect on how you relate to the role of fellowing?” Some students answered literally, thinking of how a few minutes of grounding breathing could help a session with an overwhelmed fellowee. Some responded more abstractly, trying to articulate the conceptual relationship, focusing on the role of mental health and writing. Regardless of which approach they took, each of these respondents clearly found the mindfulness aspect of our class directly applicable to their jobs as Fellows. Perhaps most notably for us as instructors, their final projects reflected back how much they valued our habitual soft start approach, nearly all sharing how they valued the community and the stronger sense of self that they had built in our time together.

Risking vulnerability

What began as a risky move for newcomer Dr. Morton-Aiken and then PhD candidate Lucy ultimately paid off, and even now that our students are out of coursework together, we continue to see the evidence of our efforts. Recent cohorts of Writing Fellows, through no fault of their own, have lacked a strong sense of community. This was the generation of college students most directly impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic, cohorts who had to reinvent what fellowing looked like in a virtual space, cohorts who spent full semesters sequestered way in dorm rooms rather than share physical space together. Fellowing was for many of them quite simply a job, another expectation to fulfill in an already full schedule. Last semester’s professional development retreat was a quiet affair, focused exclusively on the task at hand; this semester’s retreat, however, was full of the voices of this newest cohort expressing happiness, excitement, and reconnection. When they meet up in these active Fellowing spaces, we hear them greet one another in ways that reflect genuine connectedness to each other and the practice of fellowing.

But our efforts to cultivate an environment that would nourish a community of students and future Fellows who are highly empathetic and willing to focus on the needs of the writer over the needs of the writing wasn’t just about giving students a chance to sit with each other as peers. We, as the instructors, also joined in the meditation. We sat on the floor, we closed our eyes, we breathed, and we shared our vulnerability with them too. We didn’t peek and we didn’t monitor who might be tip toeing in late. We may well have looked very foolish to our students, should they choose to glance at us on the floor with our eyes screwed shut and mouths open, but nevertheless, we committed to the practice, to taking those ten minutes to breathe, to enacting this closed-eyed vulnerability publicly and to model what it looked like to take space for ourselves.

Our choice here matters because as instructors, no matter how we present ourselves or aim to decenter ourselves, ultimately we are still the figures of authority in the classroom. Making space for the practice, and then sharing in the practice, however, means that we use our embedded authority to subvert the typical expectations and power dynamics. Though unfamiliar and sometimes uncomfortable for students accustomed to instructors stressing how quickly they needed to “dive in” to the material and “get through” content, we purposefully modeled a mindful approach by checking-in with ourselves in silence at the start of class. Instead of prioritizing punctuality and classroom participation, we demonstrated our values to the centering of one’s self, sitting in the present moment, and listening to what our bodies need. In transitioning to five minutes of free-writing immediately after meditation we explicitly linked that practice of seeking mental tranquility with the practice of writing. And by gently inviting students to share out, if they felt inclined, we gave them an opportunity to practice inviting an audience into their thoughts, some even revising in real time as they searched for the words aloud they weren’t able to find on the page.

The takeaway—put on your own oxygen mask first

Dr. Morton-Aiken would regularly start class by asking about how the students were feeling, giving them space to simply be humans before they had to be learners, reviewers, or achievers. She also modeled the humanness and price of teaching without investing in the self, intentionally sharing how her own burnout while teaching and parenting in a pandemic led to her own meditation practice in the first place. Lucy, as a PhD candidate actively juggling the pressures of dissertation writing while on the job market, shared her struggle to balance the multiple identities of a graduate student (student, instructor, emerging expert, junior colleague, writer) in ways that did not harm her mental health. We highlighted through action the fact that, since writing is a “purposeful, socially situated responses to particular contexts and communities” (Hyland, 2003, p. 17.), our students needed to be aware of their unique and evolving contexts and community when engaging with fellowees who might come from vastly different starting points.

By the end of the course, the students of 1190M had heard over and over again that our lived experiences shape who we are and how we use language in the world, and that we all carry the baggage of our days with us into writing. That cognitive noise means we cannot effectively facilitate the growth of someone else as a writer if we are still in our own mental stuff. A habit of mindfulness supports both the calming of our own mental and emotional health; just as importantly, it helps to cultivate an awareness of the self and one’s positionality, which is critical to inclusive teaching and facilitating the growth of a writer.

By dedicating the first fifteen minutes of class to meditation, reflection, and sharing we inadvertently mirrored a writing process that negotiates the internal and external influences and pressures to develop a text—in this case, the self—so that we might connect more effectively with our audience—the student writers being fellowed—to achieve our goals as facilitators of writing. Writing is happening all the time, not just when we are writing; meditation has helped our students start to grapple with this idea of writing as a holistic, embodied experience. While we may not be able to solve the mind-body problem with a semester’s worth of Tuesday meditations, we can give our students permission to take a breath, to accept themselves as they are, and to live at ease with who they are.

Works Cited

Campbell, JoAnn. “Writing to Heal: Using Meditation in the Writing Process.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 45, no. 2, 1994, pp. 246–51. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/359010.

Emmelhainz, Nicole. “Tutoring Begins with Breath: Guided Meditation and Its Effects on Writing Consultant Training.” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 44, no. 5–6, Jan. 2020, pp. 2–10.

Moffett, James. “Writing, Inner Speech, and Meditation.” College English, vol. 44, no. 3, 1982, pp. 231–46. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/377011.

Morton-Aiken, Jenna and Dani DeVasto. “Any Chance You Want to Work on This Together? I Mean, Taking on More Seems like a Poor Choice, but This Looks Cool.” The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, no. 6.2, Summer 2022, http://journalofmultimodalrhetorics.com/6-2-morton-aiken-and-devasto.

Panton, Rachel. ““You Good, Fam’?”: Mindful Journaling and Africana Digital Dialogic Compassionate Rhetorical Response Pedagogy during a Pandemic.” Recollections from an Uncommon Time: 4C20 Documentarian Tales, WAC Clearinghouse, 2023.

Pennebaker, James W. Writing to Heal: A Guided Journal for Recovering from Trauma & Emotional Upheaval. New Harbinger Publications, 2004.

Sphorer, Erika. “From Goals to Intentions: Yoga, Zen, and Our Writing Work.” Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 33, no. 2, 2008.

Lucy McInerney is a final year PhD candidate in the Department of Classics at Brown University. She graduated from Dickinson College with a BA in Classics in 2015 before earning an MPhil in Greek and Latin Languages and Literature from the University of Oxford in 2017. She is currently writing a dissertation on the use of visual detail in the 5th century CE Latin epic poem, the De Raptu Proserpinae.

Jenna Morton-Aiken serves as the Senior Associate Director for Writing and English Language Support at Brown University and teaches in the English Department. Dr. Morton-Aiken is a teacher, scholar, and program leader who specializes in rhetoric and composition. Prior to arriving at Brown, Dr. Morton-Aiken was an assistant professor at Massachusetts Maritime Academy where she taught college writing, creative short story and nonfiction, business and technical writing, and writing support courses. She also served as MMA’s Writing Program Administrator and director of Writing Across the Curriculum. She earned her Ph.D. in English from the University of Rhode Island and M.A. in Creative Writing from Brunel University.