By Xiran Tan, Wesleyan University

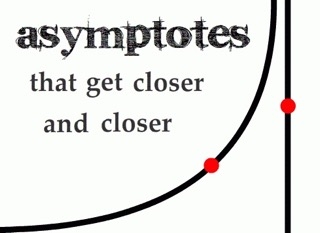

“Translation is an asymptote: no matter how close we try to get, there’s always a space between the two bodies and that is the space where we live.” — Antena Aire (language justice and language experimentation collaborative based in LA and Houston)

My linguistic and physical existence feels much like the in-between space between the asymptote and the curve. The former infinitely approaches the latter yet never touches. Pulled back and forth between Mandarin and English, and drifting away from my first language Cantonese, which was not allowed in Chinese public schools, I desire to come close and hold onto each language. I translate and retranslate myself; yet, am I there? Can I ever touch the curve that is intelligibility, perfection, and ownership?

During my time as an undergraduate peer mentor at Wesleyan University’s writing center, I have been reflecting on my entanglement with language and working with mentees to traverse different linguistic landscapes. In this blog post, I recount two stories with my writing mentees that pushed me to ponder the ownership of language, time, choice making, and clarity through the practice and metaphor of translation. In the end, I offer a multilingual support training syllabus inspired by such reflections.

Who owns a language?

I took several deep breaths walking into my very first session on the job—meeting with my thesis mentee. As part of the mentor program, we were to meet every week for around an hour to work on their senior undergrad thesis, which is typically a year-long project around 100-200 pages. For the first few sessions, I felt like a duck frantically paddling underwater. As my mentee—self-motivated and organized—brought in substantial drafts and specific questions every week, I tried to appear knowledgeable and confident, while hoping there wouldn’t be words that I didn’t know in their newest chapter. Under the water, there was always an unsaid question: could I actually be helpful as a junior and a non-native English speaking international student to white American senior students?

Still, we paddled along. Until in the middle of the semester, we were discussing a sentence level question when they paused and said, “Sorry, I need a bit to translate these words into English in my head because they came to me in my mother language.”

Much has been written on multilingual students’ tendency to apologize as a disclaimer for using English the way they do. For example, UConn’s writing center practitioner Robert Zatryb, writing in Another Word, reads the “sorries” as students’ insecurity for their expressions of English, which, though enwrap so much of their unique linguistic and cultural identities, are often labeled by “native-speakerism” as a deficit form of native speakers’ “better” version of English. My mentee’s sorry and my anxiety grow out of the same ideology that only native speakers can “own” the language.

Slowing down the ever-demanding academic production

My mentee was also sorry for the pause that they were taking. It seemed like the time used for translation was detracting from our otherwise productive session. The notion of time in higher education is largely derived from the Judaeo-Christian tradition and European colonial temporal logic, as argued by Education Studies scholar Riyad A. Shahjahan. The former conceptualizes time as irreversibly propelling towards progress and salvation, and European colonialism further categorizes individuals into “lazy/industrious … believer/heathen … developed/undeveloped” according to whether they use time “effectively” towards “productive” ends, like earning entrance to heaven (Shahjahan 490). The use of time then becomes a moral question (492). In college, faced with numerous deadlines and the shrinking academic job market, it feels sinful to not spend time furiously composing the next thesis chapter or book manuscript (492).

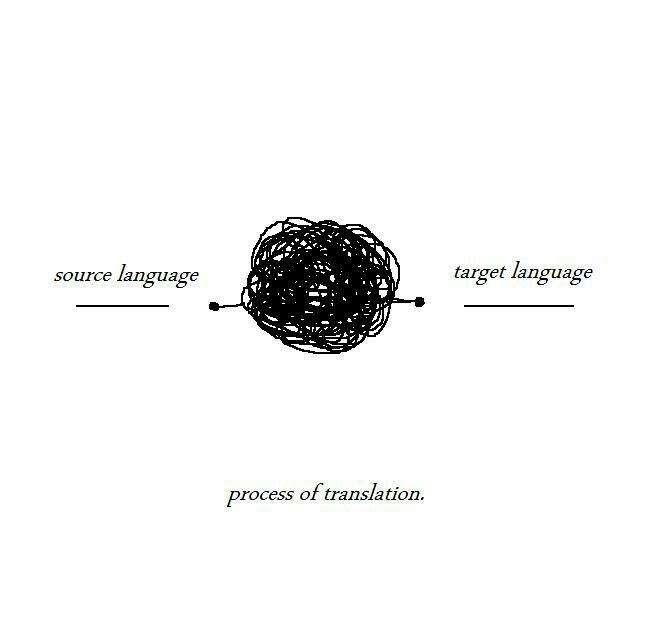

Therefore, translation needs to be apologized for because it is “lazy” time not directly spent on the final product. It is a lag between my mentee’s thoughts and output that has to be legible in the genre of a written thesis approved by this English dominant university. Those who need to translate are thus “slower” or even “less developed” than the progress that English and English-speaking institutions are supposed to lead. It feels shameful to bring up a “less modern” language in this public, academic setting because we should show up already fluent, professional, written, kept up with the institutional timeline, comprehensible by the systems in power.

Translation as choice and self making

But of course, we are not always fluent, nor any of the other things. I let out a big sigh and almost eagerly told them that it was totally fine to pause and that I wasn’t a native speaker either. I gave them some time to ponder the translation and then suggested doing it together. We talked about the word’s forcefulness in the original language, searched how different versions of the translated phrase were commonly used in English, then made a decision based on the context of their paragraph.

If my mentee was to ask which translation was “better” in the first few sessions, I might have just picked one for them because a mentor should know that “this is just how American people say it.” But the moment of my mentee requesting to pause had wrestled power back from the abstract ideal of a native speaker and an all-knowing mentor. I felt more comfortable saying, “I am not sure, let’s look up its conventional usage in context.” I was conscious of my wording that I was not finding a “better” or “correct” verb; instead, together, we were looking up how published articles “customarily” used the phrase. Now as I am responsible for co-training the new tutors, one of the first things I encourage them to think about is the power of small words and the power of vulnerability: how they reinforce or challenge dominant language ideologies and mentorship power dynamics.

As the mentorship program progressed, my mentee and I had more time to talk more about our linguistic backgrounds. Their thesis was about Balkan politics, the region from which their family came as refugees to the US, and after its completion, they were planning to translate it for her family. Into what language? Until I asked, they kept vaguely referring to “my first language” because they spoke a dialect of Bosinian, which was almost identical to Serbian and Croatian, and it was too confusing to explain. I later saw on their appointment intake survey that they had put “Bosnian/Serbian/Croatian” for the language(s) they used other than English. How we translate, retranslate, fashion, and refashion ourselves in between the slashes between languages that are forcefully separated by political powers. In the training that I later designed, I was inspired to emphasize language dominance was not natural but rather a product of imperial, colonial, and political forces that impact how we even name or identify our languages.

Looking back, I was also surprised by how far we’d come from the binary identities, “international student of color vs white american student,” that I had assumed in the beginning of the program, and my anxiety that I couldn’t be helpful enough. This translation moment unveils the open secret that we never arrive already fluent. In a sense, we never will be fully fluent; rather, all of us move through the world by constantly negotiating and interrogating meaning making. Be it as grand as how to identify and identify with our languages to the granular scale of word choice, we are always negotiating in between these choices, like the gap between the asymptote and the curve. It takes effort and indeed courage to take a break from the forever forward running time and give space for such negotiation. Because only through it we can actively learn instead of compulsively produce. Because only through it that words acquire new life and writers slowly take on new voices.

Translating clarity for different communities

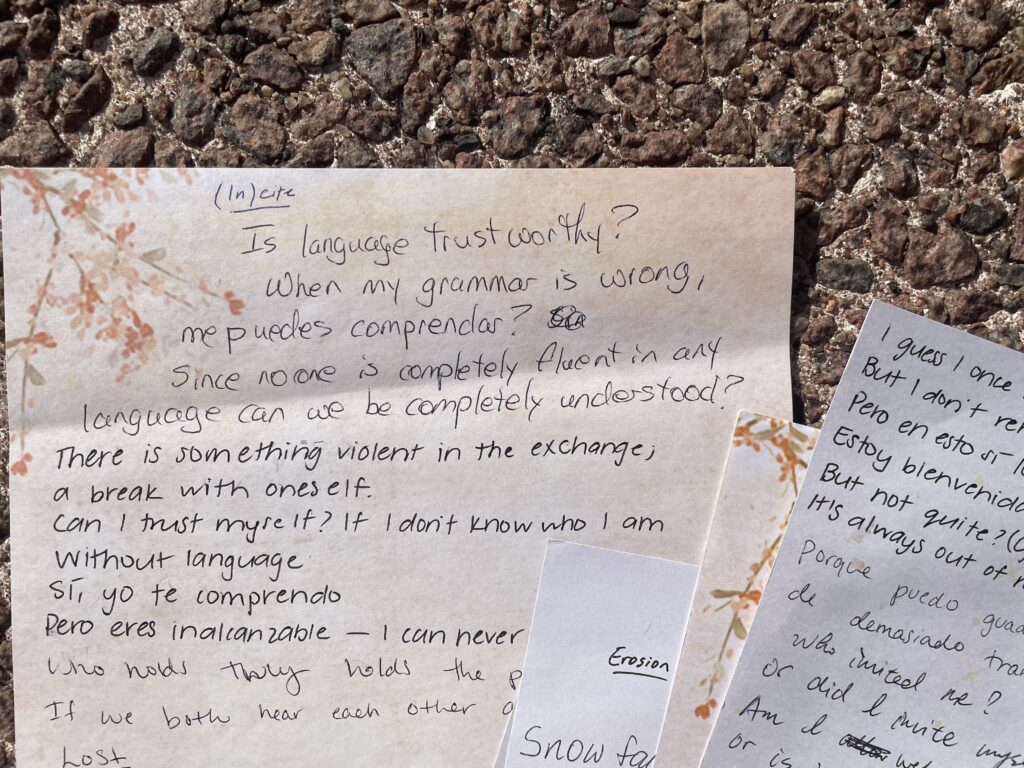

In another session, I brought in an English poem for my other mentee and I to each translate half into Mandarin Chinese. When we were both done, I looked at their part and was surprised by how different it was from mine. While I took a very literal approach, careful not to deviate from the original word order and line breaks, making sure to explain historical and political references in the footnotes, they took the liberty to restructure the stanzas and added their own words to flesh out metaphors.

The general mentorship program at my writing center is designed to be flexible for the mentees to curate their experience. My mentee, a first year international student, was very clear from the initial survey that they wanted to use the program to write creatively, as a space secured from external academic pressure. Preferably in Mandarin Chinese, they added, because they felt uneasy with English (academic) writing’s emphasis on clarity and rather leaned towards Chinese’s ambiguity.

Ever since they brought up the point about clarity and our translation exercise, I’d been asking myself: What does it mean to be clear? Who gets to declare something as vague? Whom are we making ourselves clear for? I am so trained to uphold direct and succinct writing that ambiguity leaves me insecure. Yet at the same time, part of me understood my mentee’s confusion and discomfort with the expectation to be clear, as I feel that such valorization of clarity largely stems from a European Enlightenment and colonial emphasis on rationalism—everything can and needs to be understood, defined, categorized, and mastered. By rendering ourselves to be completely clear and transparent in the university is then, to an extent, surrendering oneself to such a set of intuitional logic and be completely known through the dominant language and rhetoric.

But just as the messy process of translating poetry, we never arrive all-knowing and known. As poet and translator Robin Myers says, in summary of Johannes Göransson, “poetry and its translation as a crucial contaminant, an exuberant, transformative life force that disrupts long-prized ideas—ideals—of genius, individual authorship, literary lineage, and intellectual property,” translation and my mentee’s trans-lingual questioning disrupt clarity as a fix quality to be presented to the reader by a single master of language.

Rather each translator and writer make distinct decisions to negotiate meaning making among the writer’s (and translator’s) ways of knowing, their literacy background, and literary traditions of the reader’s community. And clarity arises at the intersection. As such, coming from different backgrounds, some readers are drawn towards the words’ technicality and etymology, as I tried to capture, while for others, poetry’s beauty lies in an affective atmosphere that my mentee tried to paint without bluntly direct definitions.

In academic papers, similarly, the writer translates abstract mental processes into concrete words that hopefully evoke a similar image in the reader’s scholarly community. The writer’s decisions drive the translation’s asymptote closer, yet do not fully touch the reader. Papers do not present packaged knowledge ready to be consumed; rather, meaning is reached through the writers’ molding and stretching of words to work out complex ideas and the reader’s empathetic engagement. In the gap between the asymptote and the curve is the shaping of the writer-reader community’s comfort zone, the desire to think (or feel) through ideas, the yearning to know, and the impossibility to fully grasp yet willingness to go along for the ride. In between the gap is where learning and clarity happen.

How do we cultivate grace and courage to embrace the gaps and the fact that we are never fully there? How do we value the fact that writers keep trying anyways? How do we support our students to do just so: moving closer to clarity as they see it, while slowing down in this English dominant, ever forward moving institution?

After working as a peer mentor, I became a full-time staff member at the writing center. Partially inspired by my interactions with the above-mentioned mentees, I developed a six-week multilingual support training offered to the peer mentors on our staff. It is an optional, paid training in the form of an hour long discussion every week with assigned readings. I share my syllabus below with in-session activities in the training’s first iteration.

Multilingual Support Training

-

Goals

-

Week 1

-

Week 2

-

Week 3

-

Week 4

-

Week 5

-

Week 6

This training corresponds to your role as both (1) a language user and writer and (2) a mentor.

- It creates an alternative space to reflect critically on the dominance of English and language’s role in both individual identity and societal power structures.

- It is also an extension of the general new tutor training that provides tools specific for working with multilingual writers (or writers new to US academia) through a non-punitive, agency-oriented lens.

Ultimately, combining these two goals, the training provides frameworks/scaffolds that help you and your tutees consciously think about and cultivate your relationships with language and writing, while working within often monolingual academic standards.

What English are we all using here?

Questions to consider:

- How do we understand the history of English as a dominant language both globally and at Wesleyan?

- What are the colonial, political, economic implications of English’s success as a global language?

Readings:

- Robert Phillipson, “English for all?.” Linguistic Imperialism, pp 5-11

- Robert Phillipson, “A working definition of linguistic imperialism.” Linguistic Imperialism, pp 46-50

- Rosina Lippi-Green, “Language ideology and the language subordination model.” English with an Accent: Language, ideology, and Discrimination in the United States, pp 63-67.

Free-write prompt:

- What languages do you use? What is your relationship to these languages? Specifically, what’s your relationship to English? How did you learn it? What do you like and dislike about it?

- Why are you interested in taking the multilingual training? What do you want to get out of the sessions?

Thesis, argument, claims – what are they?

Questions to consider:

- What is a claim and why do we write it?

- How to introduce it to students from academic traditions that may not require or encourage claim-making, while affirming their background?

Readings:

- “ Academic Writing Across Cultures” Spreadsheet that our writing center developed by informally interviewing students trained in these writing cultures

- If interested, there is a link to an article “Academic Cross-Cultural Differences – Academic Writing” at the end of the spreadsheet.

- Hannah J. Rule, “A future without thesis statements,” Composition and Rhetoric in Contentious Times, 2023, pp. 183-196

Free-write prompt:

What is a thesis or a claim? When do we need and don’t need them? Pros and cons of having a thesis? What was your experience doing/explaining the work of claim-making? Through it, what did you realize about the way you or your student think and write? How do you feel when being told “you don’t have a thesis?”

Activity:

Practice approaches to respond to sample thesis-statements-in-formation.

The ways we use Englishes

Question to consider:

Given the reality of English as a dominant language, as we discussed in the first session, how do we recognize, give space to, and foster different kinds of relationships to English?

Readings:

- bell hooks, “language,” Teaching to transgress : education as the practice of freedom, pp167-176.

- Flora Aurima Devatine, Translated from French by Jean Anderson. “The Lagoon of Languages,” Words without Borders.

- Robin Myers, “Hosts and Guests,” Words without Borders.

- Maham Hasan, “Jhumpa Lahiri on Loving, But Not Yet Trusting, the English Language,” Vanity Fair.

Discussion questions:

- What is each author’s relationship to language(s)?

- What are some imagery and metaphors they use to describe this relationship?

- Favorite quote? Do you relate to it if at all?

Activity:

Collaborative poetry: Each person will start with a piece of paper and write 2-3 lines of poetry then pass the piece of paper to the next person. Each round takes around 3 minutes to give time for each writer to read the lines before them and compose their own. The last round can be used for coming up with a title.

Encourage students to think about the metaphors from the readings in relation to their own linguistic practice and use any or all the languages they know.

Being clear and responsible? – analysis and citation

Questions to consider:

- What does it mean when professors comment “say more” and what does it mean to be “clearer”?

- What do citations do and how to cite non-English sources?

Readings:

- Annabel Kim, “The Politics of Citations,” Diacritics, Volume 48, Number 3, 2020, pp. 4-9.

- James Camien McGuiggan. “Meaning beyond definition,” Aeon, April 2023.

Activity:

Discuss: What does analysis do in academic papers? What does feedback like “vague,” “say more,” “unclear” mean? What does clarity mean to you? Is it bounded by culture and genre?

Practice: Select an essay for tutors to color code and come up with questions they will ask to prompt the writer to further their analysis.

Code meshing and translanguaging

Questions to consider:

- How can our space welcome multitudes of “codes” of Englishes?

- How can multilingual students leverage their languages as resources?

Readings:

- Vershawn Ashanti Young “Should Writer’s Use They Own English?”

- Suresh Canagarajah, “Codemeshing in Academic Writing: Identifying Teachable Strategies of Translanguaging.”

Activity:

Draw where and when you use different languages/dialects/registers of a language—it can look like a flowing river or a venn diagram.

What is grammar? What makes a sentence?

Questions to consider:

- What does grammar do?

- How can you affirm students’ choices on a sentence level (even when you don’t understand the subject matter)?

- Final thoughts and questions on how we move through [your university] as language users?

Readings:

- Rosina Lippi-Green, “Grammaticality and communicative effectiveness are distinct and independent issues.” English with an Accent: Language, ideology, and discrimination in the United States, pp14-20.

- George Gopen and Judith Swan, “The Science of Scientific Writing,” American Scientist.

Activity:

Reading examples from “The Science of Scientific Writing” and practicing working with sentence level clarity.

Works Cited

Antena Aire. “A Manifesto for Ultratranslation.” Antena Pamphlets: Manifestos and How-To Guides, 2014, http://antenaantena.org/libros-antena-books/.

Myers, Robin. “Hosts and Guests.” Words Without Borders, Dec. 2022, https://wordswithoutborders.org/read/article/2022-12/hosts-and-guests-robin-myers/.

Shahjahan, Riyad A. “Being ‘Lazy’ and Slowing Down: Toward Decolonizing Time, Our Body, and Pedagogy.” Educational Philosophy and Theory, vol. 47, no. 5, Apr. 2015, pp. 488–501. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2014.880645.

Zatryb, Robert. “I’m So Sorry, English Is Not My First Language.” Another Word, 7 Mar. 2023, https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/blog/im-so-sorry/.

Xiran Tan is the multilingual writing fellow in the Office of Academic Writing at Wesleyan University, CT. They gravitate towards translation because hiding in the gaps of lost meanings feels grounded when they float around places and words. With their writing center colleagues, Xiran co-authored a book chapter “Temporarily Adequate: Learning to be Enough at the Writing Center” in the forthcoming publication of Adequate: Rewriting the Logics of Success in Rhetoric and Composition. They are grateful for their co-workers and that they can use this fellowship year between undergrad and grad school to play badminton and make pottery.