By Angela J. Zito –

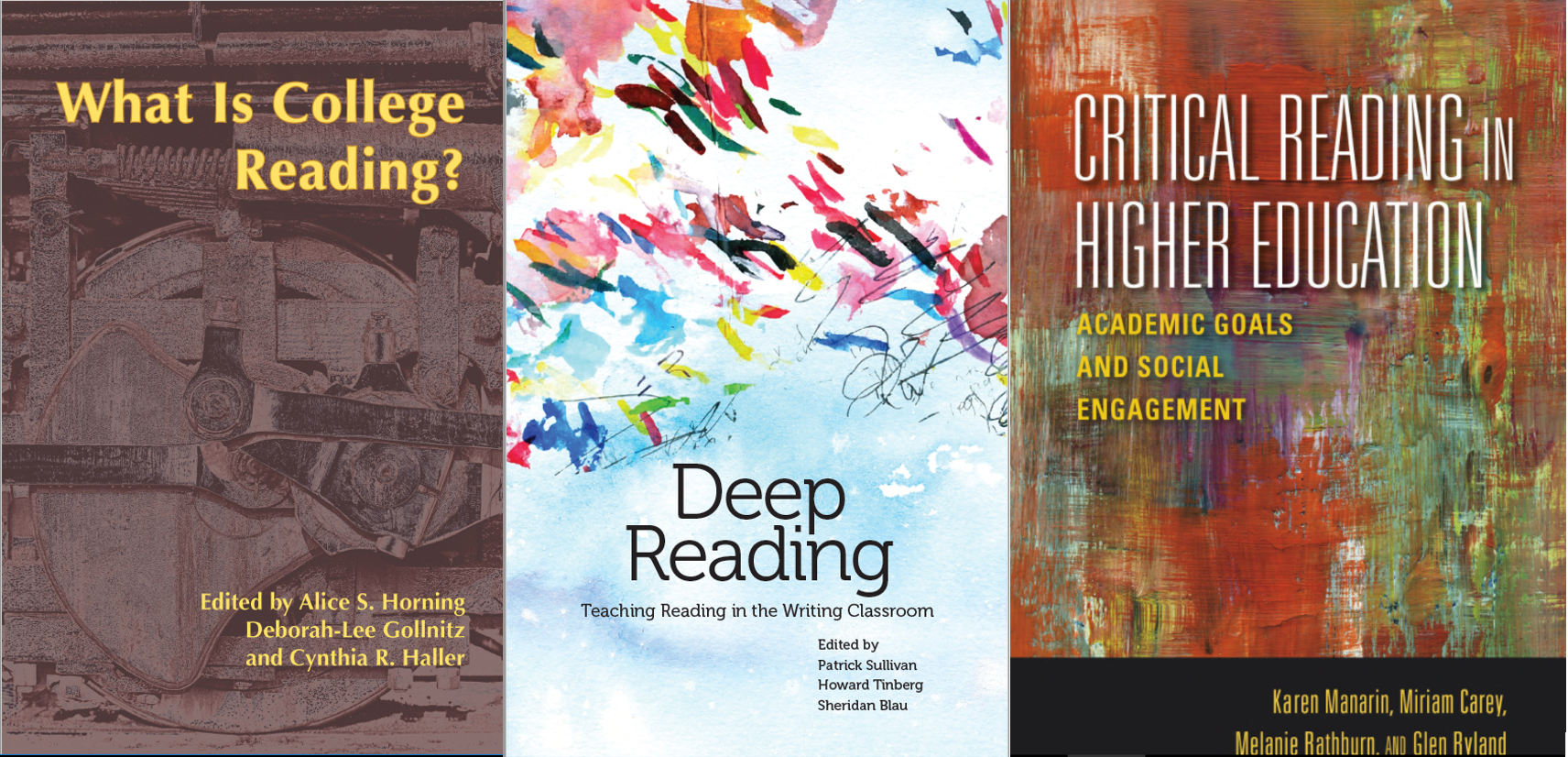

With recent publications like the NCTE’s Deep Reading: Teaching Reading in the Writing Classroom (2018), What is College Reading? of the WAC Clearing House (2017), and Indiana UP’s Critical Reading in Higher Education (2015), it seems that reading in colleges and universities is gaining a good deal of new critical attention.

Good thing. While each of these publications takes a slightly different approach to investigating the teaching and learning of reading in higher education, they all sound the alarm: The teaching and learning of critical reading is not happening very effectively across North American institutions, and there is little scholarship out there to help address that problem.

In her chapter in Deep Reading, “Writing Centers Are Also Reading Centers: How Could They Not Be?”, Muriel Harris sounds off from the realm of writing centers and writing center research, calling for more attention to reading instruction “in the form of scholarship and tutor training methods” to help tutors and student writers better realize the depth of the reading-writing connection (228). “If tutors focus on discussing students’ writing skills without being aware of underlying reading problems,” Harris writes, “tutors are tending to only part of what the students need to learn” (229).

In this post, I want to reflect on a few of Harris’s observations about the kinds of reading instruction that can and should be taking place in our writing centers, and I hope to do so in a way that extends her observations into sites of instruction beyond the one-on-one session and that raises some questions about the challenges of tutoring reading in the writing center.

“Reading to Write”

Harris identifies three provisional categories for approaching the reading-writing connection in tutor training and writing center research: reading to write, reading while composing, and reading while revising. For the sake of brevity, I’ll consider here only the first of these.

Perhaps the most obvious way in which writing center tutors engage instruction in reading to write is in guiding student writers through a careful reading of the assignment prompt. Even when, in a tutoring session, students do not themselves ask whether their writing thoroughly addresses the assignment (which they often do), the tutor’s training will typically lead them to pursue such reading-based questions—What is the purpose of this piece of writing, and/or what are the course instructor’s expectations, as outlined in the assignment?

Outside the one-on-one tutoring session, the graduate student staff at the UW-Madison Writing Center also address this component of reading-to-write in the instructional workshops we lead. For whatever genre of writing the workshop addresses—literature reviews, resumes, research posters, application essays—students typically are guided through a series of questions to pose to their writing prompt: What is this prompt asking me to do? What keywords should I pay attention to (is it asking me to “analyze,” “synthesize,” “demonstrate,” “explain”)? What goal or purpose does the prompt suggest I should pursue?

For instance, my colleague Mia Alafaireet and I recently co-led a workshop for undergraduate students writing entries for the UW-Madison Liberal Arts Essay Scholarship Competition. We devoted a significant amount of time for workshop participants to discuss the prompt (quoted in full below) with each other, to pose questions about what key terms like “liberal education” and “engaged citizenship” mean—to them and, as suggested through the language of the prompt, to the committee who will be reading their essays.

As a student at UW-Madison, you are learning at levels that are both broad (crossing a wide range of disciplines) and deep (focusing intently on a major or professional program). Liberal education across the arts and sciences challenges students to see and make connections across different domains of knowledge. Using relevant examples and details from your UW-Madison courses and experiences, please tell us how your education has provided you with the tools and skills you need to be an engaged citizen in our increasingly complex world.

Tied in with tutoring students on reading prompts and assignments carefully is helping them to read for genre knowledge. As Harris puts it, “tutors may need to work with those students who, not having a clear genre model in their minds for what they are being asked to write, will be at a loss for appropriate structures or models and flounder, not sure how to proceed” (234). For precisely this reason, our workshops also regularly make use of sample student writing to help participants recognize structural and stylistic features conventional of that particular genre. Mia and I, for instance, were sure to build in time during our Liberal Arts Essay Competition workshop for participants to read the sample essay to themselves and then to discuss its features with each other.

One component of instruction in reading-to-write that we address perhaps least explicitly in our workshops—and, as Harris suggests, in our one-on-one tutoring—is helping students develop strategies for “close” or “deep” reading of print and online texts in such a way as will aid their comprehension of the texts. So often we work with students on “higher order” concerns in their writing without recognizing underlying concerns in their reading. Harris illustrates this for us:

“Sometimes a student’s paper wanders around in search of a focus instead of a coherent discussion of the topic. Or the paper includes large chunks of undigested material copied out of a source. […] Reworking the original draft at this point is counterproductive. To help in these situations, the tutor needs to work with the student on how to read source material with better comprehension. Only after that can they have a productive discussion about how to plan and write the paper.” (230)

I read this and I think, Of course! Returning to the source material with the student goes hand-in-hand with asking the student to talk through what they’re really driving at in the paper, to articulate what they know and, in effect, what they don’t know—which is a common practice among tutors at our center. (Brad Hughes, Director of the Writing Center at UW-Madison, often jokes that we should be called a “talking center” as much as a “writing center”—a “Reading, Writing, and Talking Center,” if we incorporate Harris’ suggestion in the title of her essay.)

What I have a less clear idea of, though, is how often tutors themselves steer the attention of the session to the student’s reading of the source material, or how confident/comfortable tutors are in doing so… Do students’ source texts tend to be readily available? Does reading instruction of these texts assume or require a greater degree of disciplinary knowledge on the tutor’s part? If the purpose of the student’s writing assignment is to assess their comprehension of a course text, how would the course instructor react to a writing center tutor helping their students improve that comprehension?

As Muriel Harris and others have pointed out, there just isn’t the research out there—yet—to thoroughly address these and other questions.

What Are Your Thoughts?

I hope you’ll consider extending the conversation in the comments section below! Here are a few questions you might consider…

- Where else do you see reading instruction happening in writing centers? Where is reading instruction conspicuously absent?

- If you were to pursue a research question about reading instruction in the writing center, what would that question be? How would you design your study?

- What challenges would you expect to face—in a one-on-one session, in tutor training, in explaining writing center work to faculty—if you were to approach reading instruction much more explicitly in your practice?

Work Cited

Harris, Muriel. “Writing Centers Are Also Reading Centers—How Could They Not Be?” Deep Reading: Teaching Reading in the Writing Classroom, edited by Patrick Sullivan, Howard Tinberg, and Sheridan Blau. National Council of Teachers in English 2018, pp. 227-43.

Thank you so much for your post! I think reading assignments and writing prompts is an incredibly important and often overlooked component in the college writing and tutoring process. I recently led a workshop for our UW Madison Writing Fellows (our undergraduate writing tutors) on helping students with complex prompts. The Writing Fellows were thankful to have a chance to practice not only modelling but scaffolding prompts with students: first helping them identify the central task and then moving to secondary components. We emphasized that it is important to communicate to students that spending time with the prompt throughout the writing process is anything but remedial. Being able to break down complex prompts is a sophisticated and central skill that they can transfer to other assignments by asking themselves about the central task.

Thanks for sharing this, Calley! That’s such an important point you bring up about how reading prompts carefully – and perhaps spending time talking about reading at all – is “anything but remedial.” I’m curious if Writing Fellows have found that student writers tend to feel that way, or if perhaps they felt that way themselves at some point? What turned their thinking around?

Thanks Angela for this thoughtful post on the importance of reading instruction in our various writing teaching contexts. I’ve noticed recently how students need to work more purposefully on how they are approaching their reading as a part of their writing process. A statewide group of us writing professors from around Oregon (the Oregon Writing & English Advisory Committee) were recently participating in a professional development workshop based on a chapter from NCTE’s Deep Reading. It was a revelation to think about how students are not as engaged in their reading, especially when compared with the many complex and demanding kinds of reading expected from them at the university level. I’ll confess, too, that I have thought much less about the one-to-one coursework conference opportunities to work with students on integrating more effective reading practices into the work they understand as writing: your post has given me much to work with. As I pursue ways to improve the reading aspect of writing instruction, I’ll look forward to examining the other texts referenced. Thanks for bringing these ideas on reading and tutoring to the forefront of our work in an effort to more thoroughly imagine what writing instruction could be for our students.

Christopher J. Syrnyk

Former UW-Madison Writing Center TA

Associate Professor, Communication

Director, Oregon Tech Honors Program

Thanks for this discussion of college-level reading instruction. The questions you raise about writing center instruction apply to classroom instruction as well. For a long time we’ve studied how technology affects writing processes, but we haven’t paid such close attention to how technology affects the reading processes our students regularly engage in and how it can support the reading processes they need to engage in. Reading and listening: the “receptive” modes are essential, and we should try to design exercises and assignments that call students’ attention to these communication modes and extend their skills.