By Laura Jones-Katz

I coordinate a language learning center at an English-medium university in mainland China. My background and current context may be rather different from that of many Another Word readers. I’ve never taught native speakers of English, and I only recently made the transition from the classroom to the writing center, and from a teaching role to an administrative one. At my university, there are about 4,000 undergraduate and graduate students, and we have a small but growing international (non-Chinese) student population. Though there are a handful of native English speaking students who are welcome to access our center’s services, practically speaking, we exclusively serve non-native English speakers. English language learners have some different needs than native speakers, but also a lot of the same needs. In this piece, I’d like to discuss some of the unconventional ways our center has sought to best serve our students and to suggest that writing and learning centers are uniquely poised to program creatively and that we should do so more.

Supporting English Language Learning

The purpose of our center is to promote and support English language learning by all students at all stages. Although a great deal of that support is in service to students’ writing (as this is often the form they must use to demonstrate learning), we also aim to help students improve their listening, reading, and speaking skills. Now, that is not to say that I think the kinds of “non-writing” activities I’ll be discussing should be outside the scope of a writing center proper. After all, we need to do a lot of non-writing to grow as writers. One of the most important things I learned in graduate school was how to talk about writing. Students need practice formulating complicated thoughts and expressing them using language, and there are many kinds of activities that can foster this. Few would disagree that reading competence and lexical resource, for example, are critical for writers.

Tutoring and Workshops

But first, let’s look at those tried and true services that – dare I say – all writing centers offer. Of course, I’m referring to tutoring and workshops. And they are our bread and butter for good reason. Tutoring offers students individual feedback specifically tailored to their needs, while workshops cover a variety of relevant topics and can reach a larger number of students. In our center, tutoring is a 30 minute one-on-one consultation in which students can bring in virtually anything they are working on that is in the English language. Though this is often a piece of writing, it might also be a presentation. The tutor gives feedback, focusing first on higher order concerns like logic and organization, then points out patterns of error in grammar, and finally offers students some strategies to improve independently. Workshops cover a variety of different topics and usually last 90 minutes. Recent workshops include Precise Words for Clear Writing, Academic Discussion Techniques, and Active Listening.

Embracing Flexibility

Tutoring and workshops are popular activities that can accomplish a lot, and there is certainly space for innovation within these two forms. But we can offer more and different activities as well. One of the unique features of most writing and learning centers is their flexibility to adapt and respond to student needs. When our center opened in the fall of 2016, we found ourselves faced with a student body very eager to take advantage of every chance to improve their English, particularly their speaking. This wasn’t really surprising. Many Chinese students have few opportunities in school to improve their speaking since most provinces focus on listening, reading, and writing skills that better prepare students to succeed in the college entrance exam (gaokao), though perhaps not in university English courses. Speaking remains a weak area for most students. But how much could we do for them within the confines of tutoring and workshops?

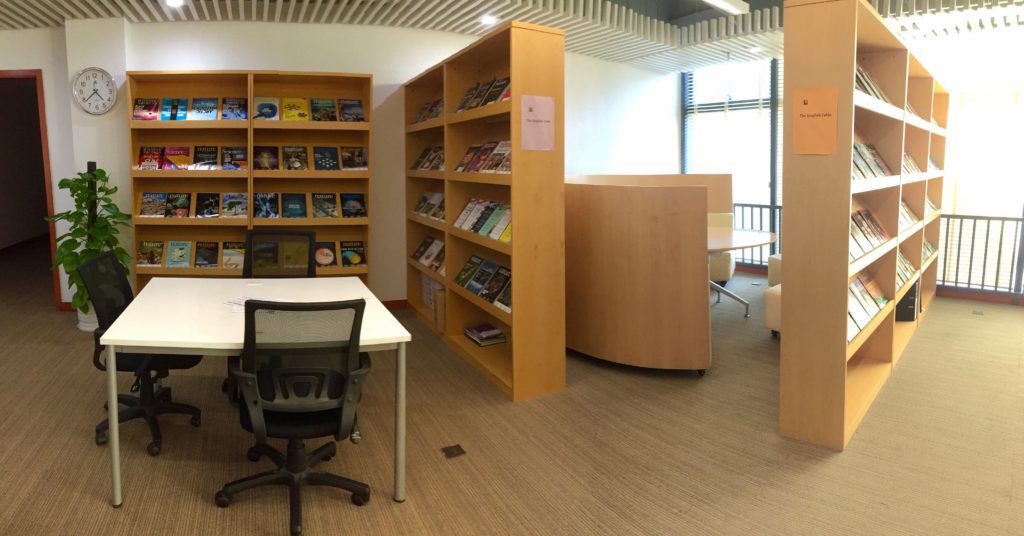

The Conversation Table

Our answer to this concern was the Conversation Table. It’s a 60-minute activity designed for 8 to 10 students that offers a low-pressure space to practice speaking in English. A teacher acts as a facilitator, introducing or eliciting topics from students, and the focus is on fluency. Apart from interacting with the teacher, Conversation Table participants also learn from peers who may come from different academic backgrounds. This activity was a huge success and continues to be very popular.

The Vocabulary Table

Following the success of the Conversation Table, we went on to introduce the Vocabulary Table, Reading Roundtable, and Cultural Exchange Table. Let me explain how each of these activities operates and what students can gain from them. At the Vocabulary Table, we introduce 10 vocabulary items on a specific topic area – for example, war, personality traits, or sports idioms. Each week there is a new set of vocabulary, and we run several sessions of the Table on different days and at different times. We choose vocabulary items that are challenging yet common. The teacher discusses the pronunciation, meaning, and usage and collocations of the words, and participants have the chance to apply them verbally and in writing. I believe that a slow, interactive, and small-scale approach can be very beneficial to our students, especially since so many of them have been taught largely via rote memorization and word lists, rather than a careful and thorough examination of words in context.

A Note About Chinese Language Learning

Here I’d like to clarify that based on my experience, the common view of Chinese education’s emphasis on rote memorization is unnecessarily vilifying. Let me digress for a moment to sing the praises of the Chinese. Through tutoring, lessons, and sheer trial and error, I have acquired “conversational” Mandarin. My son attends a bilingual primary school and has achieved near fluency verbally and reads and writes at about a 3rd grade level. Through our struggles with the language and the method of instruction (so unfamiliar to us at first), I have come to appreciate the value of memorization, repetition, and recitation. Chinese characters are a whole different animal than our roman alphabet. Simply using a dictionary is a very arduous task that requires several lessons in itself and a great deal of base knowledge about the language. It is possible to identify word “parts” and there are even some rare Chinese who as children could guess the meaning and approximate the pronunciation of a word they’d never encountered before. But Chinese schools have depended on memorization, repetition, and recitation because that is how you learn to read and write Chinese.

In English, we’ve got affixes, and word forms and families, and all kinds of information often included in an unfamiliar word that help us guess its meaning and pronunciation. And learning a single word and all its components and forms can likewise help us the next time we see a new word. This is the thinking behind our Vocabulary Table – to introduce students to only a few words, but to spend time to examine and use those words so that students are more likely to retain and employ them. Our students already know how to effectively memorize English words and their Chinese translations. What we can help them with is activating their vocabularies in their speaking and writing.

The Reading Roundtable

The Reading Roundtable is another one-hour activity designed for about 8 students. Participants are introduced to a different text each week and are guided through different strategies involved in reading that help them identify source information, bias, and main ideas. We often choose one-page articles from magazines like The Economist and Scientific American, which we read and discuss. Our thinking is that a university-educated student should be able to, upon graduation, pick up a general interest magazine on virtually any topic and have the English reading comprehension (and the interest!) to understand and appreciate the information, argument, and perspective. Questions that the teacher may raise include:

- Which magazine is this taken from? What is the issue date? Who is the author?

- What is the title of the article and what does it tell us about the topic and scope?

- How is the article structured?

- What are the author’s main claims, and how are they supported?

- How are the ideas in the article relevant to our lives, or connected to other articles you’ve read or issues you’ve heard discussed?

- What can we do when we encounter unfamiliar words?

The Reading Roundtable aims to support students’ reading development through reading strategies and exposure. I won’t belabor this, lest I sound like a judgy curmudgeon, but I don’t think our students read enough or broadly enough, and I gather that many of them don’t enjoy it much. We are currently working to re-imagine our Reading Roundtable so that in addition to enhancing their information literacy, we can better cultivate in students the pleasure of reading.

The Cultural Exchange Table

Now, as sensible and useful as this next activity may seem, it was not born of pedagogical thoughtfulness but rather temporary desperation when confronted with reduced (wo)man power. In the face of limited university resources, the flexible and supplemental nature of language learning centers makes them particularly vulnerable. That is to say, their distinctive character is at once their best asset and also their greatest susceptibility. The problems our center faces are common to many writing and learning centers–a small budget, understaffing, and a need for greater institutional understanding and support. These common problems can really challenge success. Yet, these administrative hardships also harbor hidden potential to promote a center’s growth, since they can encourage creative problem solving efforts and innovative programming.

And that’s how the Cultural Exchange Table came to be. This activity is led by an international student rather than a center teacher, which takes pressure off of teachers so that they can devote more hours to workshops, tutoring, and other Tables. The international students that led Tables this past term came from Canada, Indonesia, Madagascar, and Mexico. This Table essentially develops the same skills as the Conversation Table, but also offers students the opportunity to learn about another country and culture. This is not to say that non-native speaker students cannot peer tutor in English writing! Obviously they can be trained to do so. Suffice it to say, though, that in my current institutional environment, the ways in which our center can hire, train, and utilize students appropriately and effectively is still rather limited. We needed to ask ourselves – what can our students be trained to do, what resources do we have at the moment to provide that training, and what is permitted within university policy and culture? Making use of some of our international students was a relatively uncomplicated way to handle a rather urgent situation.

An Appeal for Experimentation and a Personal Reflection

So, these various activity Tables are the main way our center has tried to creatively meet our students’ language learning needs. I hope the readers of this post will excuse what seems unwise or unhelpful, try what makes sense, and adapt and create their own unconventional programming. As we reflect on our students’ needs, why not experiment with new activities that seek to address them in different ways?

Please allow me one final, more personal reflection before closing. I’ve grown a lot during my time leading our center, most notably in the following two ways: First, I’ve gained a deep appreciation for the smallness of the scope of my power, and I have embraced it. I’ve come to believe that understanding the boundaries of our influence is critical for doing the best and the most that we can. Second, I’ve learned that responding quickly to the unexpected is not a frustrating but necessary part of the role – it is truly at the heart of the job. I’ve tried to embrace these lessons, serve with a purpose, and experiment with programming that seeks to help realize that purpose. Between that last sentence and this next, I learned that our center will be relocating this summer. Sometimes it’s hard to know if it’s a China thing, a Learning Center thing, or just a Life thing, but–forward!

I feel compelled to respond to this article as both my parents are graduates of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and I did not even know that there was a Shenzhen branch until now. This is a fascinating look at how a Writing Center can and must creatively use space to adapt to and serve institutional needs. I love how each table is dedicated to a different activity; I think that this exclusive usage of space raises the esteem of that activity and also encourages student writers to adopt a familiar “habitus” as soon as they sit down or move to that table. They are ready to participate as they are in that space. Thank you also for your defense of memorization and recitation. It’s interesting how the most ardent critics of such techniques come from Chinese students themselves, at least in my conversations with them. I hope to hear more about your center after it moves to that new location. Best wishes on that move!

What a great example of the writing center being context specific–working to meet the needs of the students in a particular time and place, although, I’m confident that these ideas are quite transferable to many other contexts as well. I also want to echo what Antonio said about how the exclusive use of space — and I’d add, of ‘naming’ these learning spaces and events — raises their value. Having a Conversation Table, housed in your learning center, is a different thing than a drop-in conversation class, for example. And a Reading Table highlights the value and necessity of reading for learning and writing, So interesting and valuable!