By Calley Marotta and Jennifer Conrad

In May of 2020, two months after the sudden jump to online-only instruction necessitated by COVID-19, our writing center held its first virtual Dissertation Writing Camp. Co-sponsored by UW-Madison’s Graduate School and facilitated by Writing Center instructors, the central goals of this camp have always been to support writing and its production during a compressed timeline and to provide dissertators with a community of fellow graduate student writers engaged in the same effort (see this post from 2015 and this post from 2011). The decision to host this long-running camp online rather than in person felt provisional, and yet necessary amid so much upheaval.

In preparing to facilitate the dissertation camp during the early isolation measures of a global pandemic and in a social context of deep uncertainty, fear, potential illness, and travel restriction, amplified by systemic inequity and racism,[1] the not-okayness of the moment felt very clear to us. We recognized the privilege in being able to hold a camp virtually while many campus workers were still engaging in front-line work. We also recognized that talking about dissertation-writing might feel inappropriate in these contexts, while at the same time, we wanted to offer support to dissertators operating within particular timelines for completion: those for whom not writing might have consequences—professional, emotional, and even financial.

As we (two facilitators from the camp) reflect on that week now, we appreciate the openness, vulnerability, and support that participants shared with one another and with us. We value most the moments when writers were able to feel recognized as whole people whose lived and embodied experiences shape and are shaped by their writing. We follow a long history of scholarship and activism by women of color (such as Audre Lorde[2] and Gloria Anzaldua[3]) that encourages us, as white female writing instructors and administrators, to prioritize thinking, feeling, embodied writers in the context of a global pandemic and beyond. We hope that in reflecting on writing as a whole-person experience, we might encourage others to consider the particular importance, both for participants and those who seek to facilitate such spaces, of bringing the body into a seemingly disembodied (i.e., virtual) mode.

Feeling Our Way Through Dissertation Writing

Even in better times, we know that graduate school takes a toll on mental health (see articles here, here, and here—the latter of which requires creation of a free account for access). In response to this, the Writing Center has, in recent years, invited representatives from University Health Services to address dissertating and mental health, both in staff training sessions and during previous dissertation writing camps. This ongoing organizational commitment acknowledges the challenges of graduate education and highlights how dissertation writing is knotted together with writers’ mental, emotional, and even physical health.

In the May dissertation camp, we were fortunate to extend this form of exploration in a lunchtime workshop titled “An Empowered Response to Dissertation Anxiety” with Dr. Allie Murrow. Dr. Murrow completed her dissertation[4] in Curriculum and Instruction at UW-Madison and participated in the camp during her own dissertation-writing process. From her perspective as both a former camper and an anxiety researcher, Dr. Murrow discussed how her research on education and anxiety might apply specifically to dissertation writing.

According to Dr. Murrow, dissertation anxiety is “any combination of apprehensive, pessimistic, or other thoughts that can lead to a lack of productivity and feelings of hopelessness or self-doubt that impede one’s progress, enjoyment, focus, or self-confidence about completing a dissertation,” a definition that illuminates dissertation writing’s affective dimension. Further, Dr. Murrow’s elaboration on her personal response to the dissertation camp while a camper underlines the way that such emotions are embedded within the body. She reflected, “I remember sitting in diss[ertation] camp, and my heart was beating so fast, and so strong, and I remember just thinking, ‘I wonder how fast the blood inside me is going through my veins right now, and I wish there was a way to slow it down.’” Anxiety, as shown here, threads through both cognition and embodied response and cannot be easily disentangled.

Speaking to dissertation anxiety, “thesis panic,” imposter syndrome, and how to develop an empowered response to these deeply felt experiences, Dr. Murrow offered perspective on questions from dissertators. These ranged from how to manage expectations with loved ones to achieve support instead of additional pressure (answer: use a direct communication style with “I” messages, and let the other person know what responses you would find helpful) to ways to navigate anxieties heightened during times of quarantine (answer: acknowledge the reality of any felt emotions and adopt a perspective of gratitude that takes into account one’s current accomplishments).

An Empowered Response to Dissertation Anxiety

Now more than ever, students have the need and right to an empowered response to anxiety and other stressors that can accompany graduate dissertation writing. During my time as a Ph.D. candidate, and as a current facilitator of anxiety workshops for graduate students, it has been my experience that professionals have a great need for opportunities to come together to delve further into the emotional reactions and states they experience during this unique time of writing and research. Extensive participation through chat boxes, email, live comments, etc., during and after my sessions, are a constant reminder of how pervasive these anxieties can be and how normalized and non-stigmatized these challenges must become to prevent circumstantial isolation and unproductivity. Students’ open, honest, and gracious involvement invites further opportunities to question, express, collaborate and be supported in how they feel, so that they can complete this pivotal step to finishing graduate school.

In normalizing anxiety as a “natural response to stress” and something that almost every academic feels at some point, Dr. Murrow gave dissertation camp participants time and space to acknowledge their own feelings and experiences, and tools to better understand, talk about, and cope with anxiety. As facilitators, we were struck by the way participants responded to Dr. Murrow’s work with open, vulnerable, and authentic questions and comments over their microphones and in the chat box during our Zoom workshop session.

Anxiety, of course, is just one embodied response to writing, and yet we think that this workshop signaled how necessary it is to provide space to discuss the role of thoughts and feelings as a part of the dissertation-writing process.

In this section, we briefly articulate three principles drawn from writing studies and other interdisciplinary fields that we found to be particularly compelling when attending to writers as whole people in the context of our dissertation writing camp. While these principles are widely recognized as applicable to writing more generally, we include them here to further underline their importance and to address how they functioned and came to matter within the space of a virtual camp.

1. Dissertation-writing is an embodied practice.

Among other fields, writing[5], disability[6], and Chicana feminist[7] studies have drawn attention to writing as embodied practice that works through, makes demands of, and changes with the physical body in the context of inequitable power relations and conditions. While the dissertation camp was virtual, it was not disembodied.[8] Even when we, as writers, were not on camera, our bodies were affected by social and political conditions, our writing materials, and the feelings we experienced as we wrote: which, among other influences, position bodies inequitably and bring about real, material, and embodied consequences. To take into account historical and current systems of oppression and racialized surveillance, in particular, we invited participants to use their cameras in a way that supported them.[9] We explicitly encouraged writers to keep their cameras off if they chose or even to call in–inviting them, to the extent that they could, to control the way their body showed up in our shared, virtual space.[10]

To acknowledge our practice as writers operating remotely from each other and to center our writing in the physicality of the body and its surroundings, we offered an optional two-minute grounding practice before breaking out for work time each morning. While different from the sort of body-centered writing that some promote[11] (including as a form of meditation) we hoped to recognize the self operating as a body-mind continuum[12] who writes rather than a mind operating in a rarefied cognitive space. We set a timer (in our case, the Enso app) and extended an invitation to become present to the moment, offering one or two simple, body-based techniques to try as a part of this time. While our approach held something in common with mindfulness as a practice, we were careful not to name it such, due to its selected terminology emphasizing the central role of the mind/brain as well as the expectation to “sit with” sensations and feelings that might be experienced as unpleasant or even destabilizing. Instead, we gestured toward points of contact between the body and its surroundings, including onscreen images of particular locations, taken in visually, or the contact between feet and floor, or body and chair: a reminder of tactile presence. We did not place any expectations on breath or thought; the aim was simply to orient and to invite participants to a renewed awareness of bodied materiality before moving into the more nebulous spaces occupied by ideas, language, and writing. Participants expressed appreciation for this pause at the end of our opening session, before entering the workspace of daily writing.

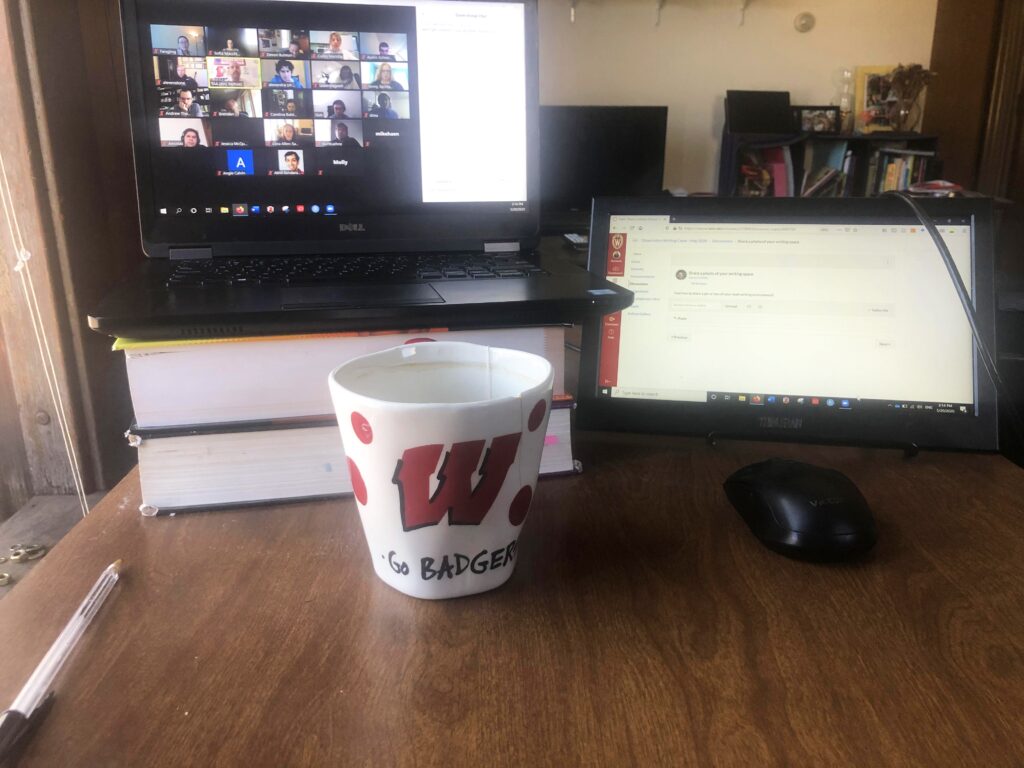

An interesting outcome that we think marked an attempt to recreate the physical in the virtual involved writers requesting that we leave the online meeting room open so that they could write together throughout the day, with cameras on in many cases, while working remotely: another reminder of the importance of community spaces, even (and perhaps especially) those created by virtual settings.

2. Dissertation-writing is a social process.

For those who participate in writing groups, this principle may feel unnervingly obvious—and yet the image of a dissertator laboring alone is a well-worn one for the reason that it is common. And so naming the extent to which writing groups facilitate not only community among writers but also writing itself feels like a necessary reminder, as Amanda Siebert-Evenstone, a then-dissertator in (and now a doctor of) Educational Psychology, noted in her reflection on the camp, which acknowledged not only the challenges associated with dissertation writing but also the reality of carrying out this activity within the context of a global pandemic. “In coming to terms with ‘things are different right now,’” she said,

I want to figure out what from the past that I want to keep the same, and what I need to understand is going to be different. But also remembering this whole time that I’ve been writing in a community, and then in the last—you know, I don’t know, what week are we on?—I’ve been trying to go it alone, and I had forgotten that I got so much power and so much joy and confidence from talking with all of you: that’s something that had sorely been lacking […] because I think it’s sometimes easy to be like “Well, I could spend 30 minutes reflecting or I could spend 30 minutes writing,” and it always felt like “Well, I should be writing,” forgetting that reflecting is work that helps the writing.

Amanda later reported setting up virtual check-ins with a dissertation-writing colleague that took place on a near-daily basis throughout the summer as she completed her dissertation: a practice that grew out of the camp’s focus on writing and reflecting together.

In each opening and closing session, we offered participants opportunities to share their goals and experiences with one another in breakout groups, as part of the large group, and in one-to-one sessions. While conversations in these spaces most often started from questions about goal-setting and strategies for writing, they tended to open up to discussions of emotions such as frustration (and “joy,” as in Amanda’s response above). We believe that staying with such emotions,[13] naming and acknowledging them, can facilitate how a group functions together and enable individual participants to take away practices that allow for a deeper experience with writing and one that brings in the writer as a whole person.

Working online, we found it helpful for students to share around a virtual table, an approach adopted from a social justice training program, Training for Change (using the template viewable here on slide 2), that allowed students to choose a place and provided an order for sharing out. We similarly noticed that the chat box became a space for active participation, where students had more opportunities to express shared experiences or to validate a comment than they would have during in-person sessions, in which only one person could take the floor at a particular moment.

Dissertators articulated that there is power not only in sharing experiences that validate their own but in the accountability created by mutual support in and through the process of writing. Cora Allen-Savietta, a dissertator in Statistics, addressed her cohort, saying, “Mainly, I found it helpful to know that all of you were going to be here writing every day. Having that certainty and routine created a kind of passive accountability, a reminder that we’re a community, we’re all working toward something together.” In a similar vein, Sofía Macchiavelli Girón, a dissertator in plant pathology, said,

Having a supportive environment, combined with the writing tips and prompts, allowed me to focus my energies into writing instead of stressing about writing. It also gave me the space to pointedly think about my personal writing process, which I usually don’t think about explicitly.

Sharing personal writing experiences can shift writing from an expected experience of cerebral solitude to one that is born out of the company of others. Writing together may offer opportunities for writers to use the affordances of online presence to voice some of the challenges that accompany their specific writing experience. As Sofía says, the group helped identify what was a “personal” writing process amidst broader experiences that others might share.

3. Levity can leverage and balance emotion during the dissertation-writing process.

Since dissertation writing is deeply activating, at emotional, mental, and physical levels, we found it helpful to provide opportunities for levity. We sought to provide participants with chances to get to know one another and to talk about aspects of their life beyond the dissertation—something that felt particularly important in what might be perceived as a depersonalizing online space.

In accordance with Dr. Murrow’s perspective that “We need to take a second, or several, every day in our education or learning process to laugh, because somewhere along the way this should be fun,” we set up optional discussion boards for sharing photographs of writing spaces, tips for writing, and even recipes (after all, writing bodies, like all bodies, require sustenance). In our closing session for the week, participants were invited not only to reflect on their experience of the camp but also to “show and share” a writing partner, whether a child, a favorite pen or desk plant, or one of many pets.[14]

We found that in the collision of personal and professional catalyzed by the pandemic, these acknowledgements of the whole person provided much-needed connection and levity (for us at least) when dog paws or a cat tail appeared on the screen. While we each experienced writing conditions in different ways, it helped in these moments to name and acknowledge the very real (and often not conducive) conditions for working on writing. Laughter, we found, can sometimes bridge the gap between brain and screen, or in Dr. Murrow’s words, that “most impossible short distance that you’ve tried to overcome before.”

Holding Space(s) for Possibility

We are still thinking about how to support writers’ intersectional[15] identities further in their ongoing work, in our newly digitized learning framework, and in the context of pandemic and ongoing injustice. As writing instructors, program administrators, and writing center staff members, how can we encourage writers to take care of themselves and their bodies while resisting the neoliberal and ableist impulse to prioritize productivity over collective self-care[16], an impulse that may in fact be more deeply felt within pandemic conditions?[17] And in addressing embodiment in the context of COVID-19, how can we design programs to de-center whiteness and prevent using embodiment, as Carmen Kynard so aptly warns, “in the service of whiteness for whom danger and death under COVID are newfound, daily realities”?[18]

Recognizing and naming what’s happening seems a first step toward taking countermeasures and recognizing the affordances of online learning. For instance,to accommodate the fact that group activities seem to take longer online, we were able to extend our opening and closing sessions by around ten minutes. In response to the fact that participants found themselves feeling more tired after a remote workday, we plan to build more breaks for the body and mind throughout the day into future camps that take place virtually. Participants, to our surprise, requested that the day itself be extended to accommodate those breaks and allow for more even pacing throughout: a recommendation that feels wise, since more breaks can also help participants avoid burnout later in the week as they develop habits for writing that can work beyond the structure of the camp. As the pandemic loses its newness, and work within virtual spaces becomes more normalized, we believe that linking feeling and thinking to embodiment—and embodied experiences of writing—are more important than ever.

At the same time shared experience can offer comfort to some writers, we recognize that being together does not automatically confer comfort for all bodies—particularly those who have long been disempowered by writing contexts that have positioned bodies as non-normative in the context of systemic racism, ableism, and homophobia and transphobia. And so we ask: As bodies write and share together, how can a focus on embodiment and its specificity of experience challenge a universal dominant experience of dissertation writing and a dominant normative body? How might acknowledging and naming the traumas, microaggressions, and areas of discomfort, which is to say forms of body-centered knowledge, contribute to a writing process—and even communities of practice—that might position writers to continue with this medium of engagement? How might we imagine and then instantiate specific, alternative forms of being-with-others in academic (and virtual) settings that weave together our disparate—and shared—experiences?

If writing is to be something that not only results in a completed dissertation but simultaneously a process that enhances, challenges, integrates, coheres, and stretches each writer to become a fuller person, then it will require us, as facilitators and witnesses to this process, to continue valuing writers over writing. Our experience with last May’s dissertation camp clarified for us some things about writing—and about dissertation-writing, in particular—that have been present and important all along, but that the current moment and its ubiquitous digital mode moved front and center in our minds.

With your help, we hope to continue to find ways to design programs that support whole writers and use writing to support whole people.

Calley Marotta is Assistant Professor of Literacies and Composition at Utah Valley University. She is a writing teacher, literacy researcher, and a mother.

Jennifer Conrad is a Faculty Associate in the Writing Center at UW–Madison, where she teaches workshops, works with students on their writing, and more.

[1] García de Müeller et al. “Combating White Supremacy in a Pandemic: Antiracist, Anticapitalist, and Socially Just Policy Recommendations in Response to COVID-19.” The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, 2020.

[2] Lorde, Audre. The Cancer Journals. Aunt Lute Books, 1980.; Keenen, Jen, Lorde, Audre, Sonia Sanchez. A Burst of Light: And Other Essays. Sheba Feminist Publishers, London, 1988.

[3] Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La frontera: The New Mestiza. Aunt Lute Press, 1987.

[4] Murrow, Allison. “From Students to Teachers: Is there Agency or Anxiety in Voices from the Field?“ University of Wisconsin-Madison dissertation, 2019.

[5] Miller, Elisabeth L. Literate Misfitting: Disability Theory and a Sociomaterial Approach to Literacy. College English, vol. 79 no. 1, 2016. pp. 34-56.

[6] Cedillo, Christina V. “What Does it Mean to Move?: Race, Disability, and Critical Embodiment Pedagogy.” Composition Forum, vol. 39, 2018.

[7] Cruz, Cindy. “Toward an Epistemology of a Brown Body.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies of Education, vol. 14, no. 5, 2001, pp. 657-669.; Darder, Antonia. A Dissident Voice: Essays on Culture, Pedagogy, and Power Counterpoints, 2011.

[8] Fox, Bess. “Embodying the Writer in the Multimodal Classroom through Disability Studies.” Computers and Composition, vol. 30, no. 4, 2013, pp. 266–282.

[9]. Will, Madeline. “Most Educators Require Kids to Turn Cameras On Despite Equity Concerns.” Education Week, October 20, 2020.; “Equity Concerns in Zoom,” Center for Teaching, Boston College, n.d..

[10] Cardinal, Alison. “Participatory Video: An Apparatus for Ethically Researching Literacy, Power, and Embodiment.” Computers and Composition, vol. 53, September 2019, pp. 34-46.

[11] Anderson, Rosemarie. Embodied Writing and Reflections on Embodiment. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, vol. 33, no. 2, 2001, pp. 83-98.

[12] Price, Margaret. “The Bodymind Problem and the Possibilities of Pain.” Hypatia, vol. 30, no. 1, 2014.

[13] Micciche, Laura R. “Staying with Emotion.” Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016.

[14] Micciche, Laura. Acknowledging Writing Partners. WAC Clearinghouse, 2017.

[15] Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Demarginializing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989 vol. 1, pp.139–68.

[16] Nagoski, Emily and Nagoski, Amelia. Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle, Penguin Random House, 2020.

[17] Ahmad, Aisha S. “Why You Should Ignore All That Coronavirus-Inspired Productivity Pressure.” Chronicle of Higher Ed, March 26, 2020.; Lorenz, Taylor. “Stop Trying to Be Productive.” New York Times, April 1, 2020., among others.

[18] Kynard, Carmen. “For Black Feminists who have Considered Solidarity/ When the Academy is Enuf.” June 18, 2020.