By Karen Best

In August I published the first installment of this two-part series on working with multilingual or English as a second language (ESL) writers in courses all across campus. In that blog post, I confessed that I had really overshot my target word length and thus would divide the content into two separate blog posts. Part 1, in sum, argued that it is important to get to know the language background of our students, that we should celebrate multilingualism, and that it is helpful to know common difficulties for multilingual—and especially ESL—students. In this post I’ll focus on suggestions for providing meaningful feedback and designing assignments from the beginning with linguistically diverse learners in mind. So, here is Part 2 in a manageable chunk that you can read with or without Part 1, although I hope I’ve piqued your interest and that you will go back and read it if you haven’t already!

I’m committed to helping my ESL writers…I just don’t know what to “do.”

Knowing some common difficulties for individuals writing in English as a second language (discussed in Part 1) still begs the question: “What do I do now? How should I provide feedback and assign a grade?” While every context is different—“context” including your own strengths as an instructor, the goals of the assignment, the student’s own writing and goals, among many others—there are some general guidelines that can be helpful.

1. Engage with your student as a writer and thinker.

Every writer wants to know that their ideas and effort matter—that something they wrote is valuable to someone. Even if a student’s primary goal may be to get a good grade, they usually still want the writing to be valuable on its own. Therefore, even if the writing is nothing particularly amazing, and even if you have read 100 papers on the topic, it is important to engage with the student as a writer and a thinker. When we demand that students engage in the painstaking writing process (and let’s be honest…it is a painstaking process for all of us), it is essential that we respond as interested readers. This doesn’t mean we praise profusely; it doesn’t mean we neglect pushing students to think more deeply and critically. It just means we show them that their writing and ideas matter.

One of my students recently thanked me for the feedback on her paper and recounted how she had just gotten an assignment back from an instructor in another class. She was disappointed when she received a grade, but literally no other feedback. I could tell the student was really frustrated and disappointed by this and had been curious to know what her instructor thought about her writing and ideas. I felt the same way when as both an undergraduate and graduate student I would get papers back without any meaningful feedback. While I acknowledge the constraints on our time and the difficulty of assessing and responding to possibly dozens of papers, we should aim whenever possible to engage with student’s writing—providing both praise and critique as appropriate.

While a big part of engaging with individual writers involves letting them know how they can improve, it is also important to acknowledge what is working well. It is important to acknowledge something—perhaps even something minor—that struck you as interesting or well-said. I often find myself writing comments such as “Super interesting!” or “I love this sentence—so clear and well-stated!” or “I love this idea. I hadn’t thought of it quite like this!” Sometimes just using an exclamation point rather than period can go a long way in these circumstances to convey that you are interested and even excited about your students’ writing. You can also provide specific writing-focused praise, especially on issues you have stressed in your class, e.g.:

- “This is a good topic sentence.”

- “Good job showing multiple perspectives and viewpoints.”

- “This intro does a great job of introducing the topic broadly and then carefully narrowing to your focused topic and thesis.”

2. Focus on content and ideas—in other words, global issues.

Even the weakest students—especially the weakest students—need to hear that something they are doing is working. In my own research regarding students’ experiences with feedback on their writing, a participant shared the following: “Even though . . . you are not a child anymore, but you still enjoy seeing instructors writing, any good things. Or just like, just the word G-O-O-D would be enough.” Another participant said about receiving positive comments that, “You just cheer up.”1

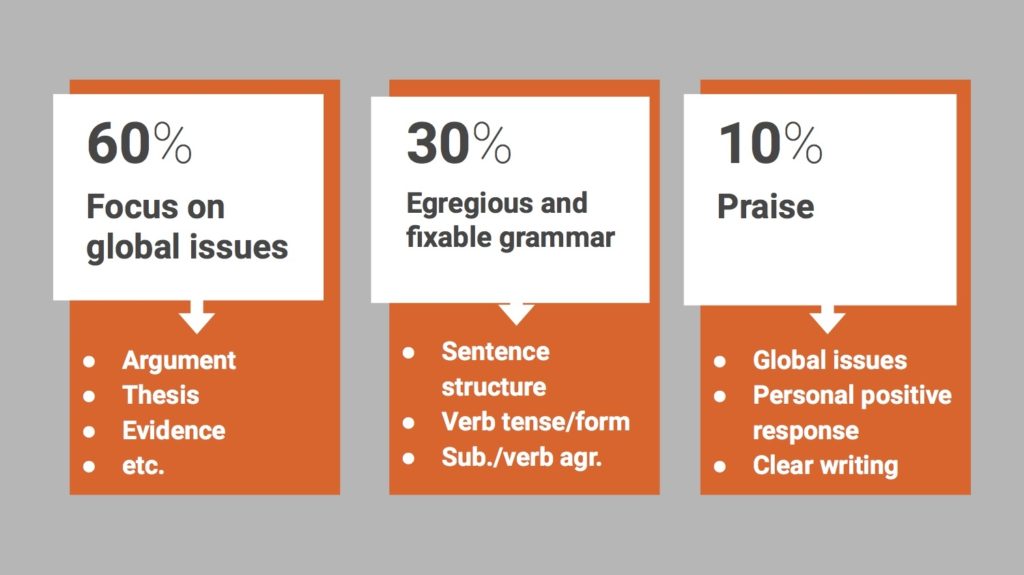

The exhortation to focus on content and ideas means that most of your feedback and most of the points in the rubric are dedicated to the “global issues”—the student’s ideas, arguments, use of sources, organization, and fulfillment of assignment requirements.2 While sentence-level concerns, such as word choice, sentence clarity, and hedging, can affect these things, focus your evaluation on the overall success (or lack of success) of the paper. Prioritize providing feedback on the clarity of ideas over specific grammar issues (although it doesn’t mean grammar issues should be completely ignored . see the next section for more on grammar).

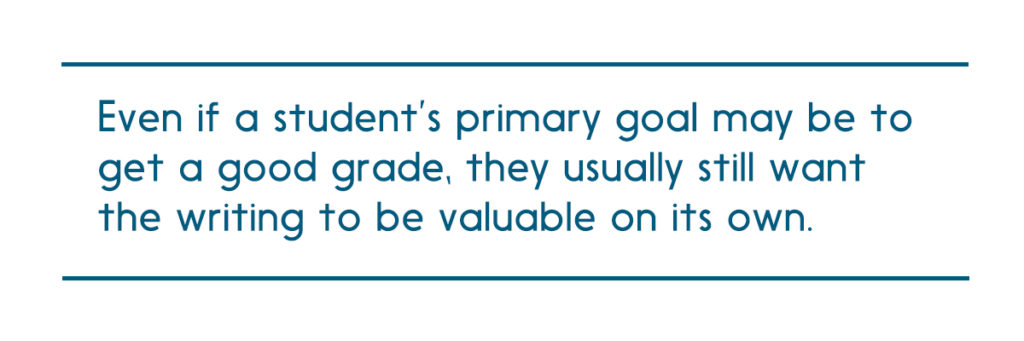

Professor Kate Viera in “Establishing Priorities and Choosing which Errors to Mark” provides an excellent example of her response to a sentence where grammar and language issues affected meaning. One sentence in a student’s paper said: “Also, it might bring better a new form of energy if only advantages of several alternatives energies sum.” In a sentence like this, the instructor doesn’t need to spend time parsing out exactly what is wrong with the sentence–no grammar terms have to be used–just point out that this sentence is unclear. Sometimes it can be helpful to give a possible reading of the sentence. For example, Viera’s comment on this sentence was: “I’m not sure I follow. Did you mean that there is or could be one new form of energy that combines the advantages of all energy alternatives? If so, what might this look like?”

3. Neither be afraid of, nor overly concerned with, “local issues.”

Some instructors feel unqualified to talk about grammar and language with students; others feel compelled to correct each grammar or language error. I personally find neither strategy helpful. Here are a couple of suggestions to keep you from either extreme:

- Focus on sentences that really throw you off—those sentences that you have to read two or three times and you still don’t fully understand. As mentioned above, you do not need to provide a detailed grammar explanation of the issue—just tell the student you are having trouble understanding.

- Focus on recurring errors. It can be difficult to know when a grammar problem is a simple error or mistake and when it represents a gap in knowledge or an issue the student needs to attend to more systematically. I don’t tend to automatically notice error patterns in my students’ writing. Therefore, when there are significant grammar problems, I skim the paper to see if there are any recurring issues that I know trip up a lot of ESL students and that tend to be viewed as especially egregious by native-speaker audiences. Errors in this category tend to be related to

- Verbs: Subject-verb agreement and verb tense are common errors that can interfere with meaning or are just very noticeable to many readers.

- Word forms: For example, using an adjective like “greedy” instead of the noun “greed”; while this isn’t the most egregious kind of error (the meaning usually can be deciphered), it is a good idea to point it out if done repeatedly in a paper.

- Vocabulary: If a wrong word is used once, it might be ignorable, but if used repeatedly, it is a good idea to address it, especially if it is a word common in academic writing or in your specific discipline.

- Ignore non-egregious errors. How do you know an error is non-egregious? You know because even though its presence or omission might call attention to itself, you can read the sentence without difficulty. Errors in this category often (but not always) include articles (a, an, the), simple spelling errors, commas, and prepositions.

- Ignore “hard-to-fix” errors. In the list above, I also categorize articles and prepositions as “hard-to-fix” issues. These are areas of language which are used in highly nuanced and variable ways; many students who didn’t grow up speaking English could study their whole lives and never master their use. There are times when these errors matter, and if you are working with an advanced graduate student already very proficient in written academic English, you may want to address these. However, for most students, I leave these alone.

- Avoid editing grammar issues with track changes in Word (or by crossing out and correcting if working with hard copies). There may be few things less pedagogically meaningful than editing a student’s paper in this way. Only the most careful students, who have unlimited time and an already-strong understanding of grammar, could benefit from this. Instead, point out the kind of error in the margin notes (for example, “word form error,” “wrong word,” “verb tense”) or even just highlight or circle grammar mistakes, encouraging them to review and fix them on their own.

- Keep expectations manageable and communicate those expectations to the student. When I work with students who really struggle with grammar and language, I try to point out one or two areas in which I’d like to see improvement. When I receive the final draft (or future papers by that student) I specifically look for improvement in those areas, rather than reiterating all the areas that could improve.3

4. Grade grammar and language—but only to a point.

One of the biggest concerns I hear from instructors is: “How do I assess ESL students’ writing in a way that is fair to all students?” Is it fair to ignore grammar errors from a non-native English speaker, when writing by a native English speaker with those similar errors might be viewed as “sloppy”? For me, the key to answering this question lies in the rubric. The bulk of the rubric should focus on the big issues: the argument, idea development, evidence, and whether the paper fulfills the basic requirements of the assignment—at least 60% of the rubric should be dedicated to these global issues. It is all right (and I’d suggest that it is good) to have high standards for all students, but the points awarded to language and grammar should be at most 20% of the grade. If you allot 15-20 points out of 100 to grammar and language mechanics, you can reasonably deduct 5-10 points (or more) from a student who has noticeable problems at the sentence level (that would, for example, mean the student receives a 50% on their grammar and language). However, the student wouldn’t be in danger of failing the class due to sentence-level problems. I strongly advise against policies that have no limit to the degree to which such issues can affect a student’s grade—policies such as a one-point deduction per spelling or grammar mistake.

5. Go back to the original assignment design.

I want to conclude by saying that a big part of everything discussed in this blog begins with a well-designed writing assignment. The Writing Center’s Writing Across the Curriculum handbook Locally Sourced has a whole section on assignment design that I will not aim to replicate here. See “Anatomy of a Well-Designed Writing Assignment”. Moreover, for UW-Madison instructors, the Writing Center has a Writing Across the Curriculum team dedicated to helping faculty and staff design strong writing assignments. So, while I will not expound greatly on stellar writing assignment design, I do want to say that if you have a lot of multilingual writers struggling with an assignment, it may be time to revisit the assignment itself. This doesn’t mean the assignment is “bad”—just that there may be ways to clarify the expectations, rubric, and the resources available to succeed in the assignment. The great news is that a well-designed and clearly communicated assignment benefits all students.

When designing a writing assignment, a few particular things that I find especially helpful for ESL students include: a “good” level of detail (neither a very general assignment, nor a ten-page explanation of a five-page paper), opportunities to draft (even if the first draft is just used for a short in-class workshop or peer review), and a clear rubric with reasonable expectations (see note about weighting of grammar versus content in the section above). Even if you are unable to grade multiple drafts of an assignment, an effective way to help students make sure they (a) understand the basics of the assignment and (b) execute them reasonably well, is to require a rough draft ahead of the final draft. Have students bring that draft to class and then conduct a guided workshop where students either analyze their own paper or a partner’s paper. I often put each requirement on a separate PowerPoint slide; explain them generally or provide examples, and then give students an opportunity to analyze and revise their draft (or provide feedback on a peer’s draft).

6. Concluding Remarks

If you took time to read to the end of this blog post, you probably already understand that teaching writing is the job of all of us at the university. Helping ESL writers become proficient users of academic English in their specific discipline cannot be done exclusively in introductory writing classes or writing centers. In the farewell blog post by former director Brad Hughes “A Valediction” he writes:

We also need to recognize that complex writing is extraordinarily difficult to do well. And it’s up to all of us—ALL of us—to help students to claim the power of writing for themselves. Mentoring students to become better thinkers and writers takes slow, patient, painstaking, often invisible work—but it’s essential work.

As you engage in this work with all of your students—ALL of your students—I’d especially encourage you to keep your multilingual and ESL students in mind. While you do not need to make special accommodations for an ESL writer, it is essential to understand that they may have slightly different difficulties than a student who grew up speaking English in a monolingual English educational context. Keeping this in mind and thinking carefully about the assignment design, assessment, and feedback can contribute to the growth and success of ALL students on campus.

Karen Best has an MA in Applied English Linguistics from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and has taught English in various contexts and capacities since 2005, most currently in the UW ESL Program and Writing Center. She has lived and worked in South Korea two times and even spent a summer teaching in North Korea. Her teaching practice and research focus on second language writing, reflective teaching, and writing feedback.

- Best, K., Jones‐Katz, L., Smolarek, B., Stolzenburg, M., & Williamson, D. (2015). Listening to our students: An exploratory practice study of ESL writing students’ views of feedback. TESOL Journal, 6 (2), 332-357. [↩]

- For more on global concerns in writing see “Global and Local Concerns in Student Writing…” [↩]

- Some helpful resources on working with multilingual writers on grammar include: Hinkel, E. (2003). Teaching academic ESL writing: Practical techniques in vocabulary and grammar. Routledge.; Matsuda, P. K. & Cox, M. (2009). Reading an ESL writer’s text. In S. Bruce and B.A. Rafoth. ESL writers: A guide for writing center tutors. Boynton/Cook.; Rafoth, B. (2015). Multilingual writers and writing centers. University Press of Colorado. [↩]

Hi Karen,

I really enjoyed reading part 2! I especially appreciate the heuristic (figure 1) that you provide here for thinking through written feedback and tailoring that feedback to different issues in student writing. I think faculty and instructors get a confidence boost from just having a set of vocabulary for identifying errors (e.g., “egregious”) and issues in written work.

I had some questions in response to a passage toward the end of the post. You write, “Have students bring that draft to class and then conduct a guided workshop where students either analyze their own paper or a partner’s paper. I often put each requirement on a separate PowerPoint slide; explain them generally or provide examples, and then give students an opportunity to analyze and revise their draft (or provide feedback on a peer’s draft).”

For instructors who would like to explore this option but feel they cannot make class time to do this, do you think there are ways to make such a workshop work effectively on Canvas or another virtual platform? Have you done this or know any ESL teachers who do this? I also wondered: if students provide feedback on a peer’s draft, do you assess the peer review or collect the students’ review feedback?

Thanks so much for such a helpful post!

Thanks for bringing up peer review Mike! Peer review is a valued part of most composition courses, but it may be less widely used in other courses, so I think discussing it in more depth makes sense. (For others reading this…feel free to chime in about if/how you use peer review.) You are right that Canvas (and probably many LMSs) can simplify the logistics for both in- and out-of-class peer review. I frequently use the Canvas peer review function and also other technology such as Google Docs.

However, the value and success of peer review are not guaranteed, and it takes some work to make it successful in each context. While the suggestion for an in-class “guided workshop” in the blog post does take class time, I find it is one of the easier and more guaranteed ways to help students review their writing ahead of a deadline. When I do peer review for major assignments, I take class time to “teach” peer review; students then review their peers’ papers at home so they can give the most meaningful feedback; THEN the next whole class period is devoted to reviewing the feedback and providing oral feedback face-to-face.

Alternatively, setting aside 20 minutes of class (or even a whole class) to help students review the requirements of the assignment, analyze their writing (or part of a peer’s writing), and ask questions is a simpler–yet still beneficial—exercise, although its benefits may be more related to the basic requirements and expectations of an assignment, rather than critical analysis of the argument, evidence, and organization.

Reading your post, I am reminded of the importance of praise. When I teach writing, I often feel my job is pointing out mistakes so students stop making them, but it is just as important to point out success to reinforce it (and to perhaps make the criticisms easier to digest). I must remember that it takes me just a moment to make a small sign of a job well done – and as you said, that praise can make a world of difference. I’d like to set a goal for myself of writing at least one encouraging comment per section for each student (especially since it is often those students who may get the most criticism who most need the praise). Thanks for the positive inspiration as our semester gets started!

Thanks for reading and commenting! One of my colleagues shared with me that he always puts a short summative note of praise at the very top of each paper. This way, he makes sure not to neglect that positive feedback can easily see if he has forgotten it. I’ve tried to start doing this, but it hasn’t become routinized yet.

Reading this post reminded me of one of the practices Professor Markus Brauer suggested in his talk, “Inclusive Teaching: Evidence and Practice” from the fall 2019 Teaching Academy’s Fall Retreat. He stressed the importance of reminding students that as instructors, we have high standards AND we believe that our students can meet these standards. Like Shauna, I would also like to commit to including more commentary praising student efforts. In addition to such praise, letting students know that we believe they can improve their writing can, as Brauer’s research has found, increase student motivation and outcomes. Thank you for the well-crafted summary of a best/better practices approach to working with our multilingual writers, Karen!

Two sentences stood out for me:

1. “This doesn’t mean we praise profusely; it doesn’t mean we neglect pushing students to think more deeply and critically. It just means we show them that their writing and ideas matter.” I like this statement. It reminds me that respect is at the heart of editing. We should respect the students as fellow writers who are doing their best to communicate their ideas. This matters.

2. The great news is that a well-designed and clearly communicated assignment benefits all students. This reminds me of when I first taught native speakers of English (after decades of ESL teaching) and thought that my speech and directions should be speeded up. But I found that the careful language in directions I used for my ESL students also benefitted the native English speakers.

The message that you have left in the section ” Engage with your student as a writer and thinker” is something i have always believed in. Making students or any other writer feel that their writing and ideas matters, can be a big constructive force. Thanks for the article