By Rachel Azima, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

So what could an overwhelmingly queer fandom in 2022-23, the aggressively cishet space of a wedding planning message board in the early aughts, and writing centers possibly have in common, besides being spaces/communities where I have been or am an enthusiastic participant? More than you might imagine, it turns out.

Fandom Shenanigans

Let’s start with the fandom, my newest community, and work backwards. I’m only going to tell you which one because I think everyone should watch the show: Our Flag Means Death (commonly abbreviated to “ofmd” by fans) on HBO Max. In Summer 2022, I created an alt Twitter account—no, don’t try to find me!—so I could engage with fan content and connect with fellow fans. I quickly discovered that in addition to tweets about the show itself, with all the associated memes and outpourings of enthusiasm and (sometimes dire) internal disputes, this fan space is also a site of disclosure, both of mental health struggles and other, less sensitive sorts of personal information, such as selfies.

Not only that, but I also found a pronounced culture of gassing each other up—that is, giving over-the-top compliments, praise, and encouragement:

Selfie posting tends to be greeted with effusive, hyperbolic affirmation. I would be lying if I said I haven’t availed myself of this and enjoyed the validation that comes with posting photos, especially as a middle-aged person who finds themself becoming increasingly invisible—in some ways a welcome change, given that attention I received in the past generally stemmed from my biracial identity and came in the form of being asked “where are you from?” ad nauseam.

But beyond just the generous sharing of compliments, in ofmd Twitter I found a community ready to jump in with words of support or distractions or funny memes when someone was feeling down. A place where people could share creative work of any kind and receive encouragement and praise.

I don’t mean to overstate the positivity; especially at the time of this writing, when we are between seasons one and two and fans are starved for new content, every day brings more online discourse of the sort that’s familiar on Twitter in general. But whenever I have reached out to this community for support, I have received it, without fail. I’ve formed genuine online and offline friendships. It sounds weird to say, but I’m not exaggerating when I tell you it has transformed my life.

Message Board Adventures

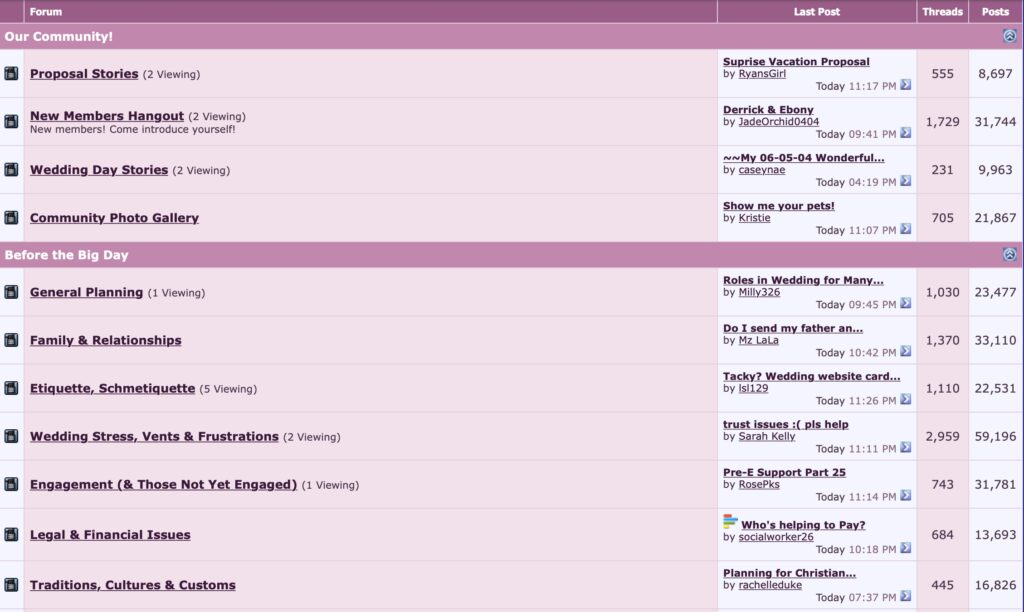

And honestly, I found it easy to slot myself into the (largely) supportive world of ofmd Twitter: I trained for it almost 20 years before on the wedding planning message boards associated with Ultimate Wedding, a long-defunct wedding planning website. Here too the tone was one of positivity and support: one would never dream of telling a bride she looked anything but beautiful in her gown, or that the bouquets or centerpieces she’d chosen were unattractive. We were there for each other around every conflict with family, every plan that went awry.

I didn’t purposely try to get anyone’s attention on the boards; I just tried to be encouraging and engage wherever I could—and, if I’m being honest, I was avoiding writing my dissertation at the time, so I spent more time online than I should have. I loved giving supportive advice and sharing my opinions any time folks asked what hairstyle to choose, or how to navigate a delicate situation with in-laws, or any of the other myriad decisions that seemed so fraught at the time. (Seeing my little bar of “reputation points” growing didn’t hurt—board members could award these with a click any time they saw someone being particularly helpful.) I was soon invited to be a mini-moderator—the specific title of which I can’t remember, but the role entailed answering questions and fostering conversation.

Eventually I was invited to be a Community Leader, or CL (moderator), which meant I had responsibility for enforcing community guidelines and other behind-the-scenes work. Although some of the conversations and topics on the forums were eye-rolling at best, in their adherence to traditional gender roles—folks planning to include outdated traditions such as the garter toss made me silently cringe, and my decision to keep my last name seemed shocking to some—the overall culture of support and validation that tied the community together made the experience addictive. Silly as it was, I loved it, and some of us formed real bonds with one another. Nearly 20 years later, I am still friends with two fellow CLs.

Learning How to Praise in the Writing Center

But again, my ability to function as a constructive member of this community didn’t come out of nowhere. I had ample relevant prior experience: giving specific praise in writing center consultations. As a Writing Center tutor at UW-Madison, I’d absorbed the lesson thoroughly that praise should be both genuine and specific. One had to mean it, and it had to be grounded enough to be compelling.

And having been part of Madison’s Online Writing Center for a number of semesters during the purely asynchronous, email feedback days, I had gotten considerable practice giving this kind of praise in writing. As Bradley Hughes, Paula Gillespie, and Harvey Kail demonstrate in the Peer Writing Tutor Alumni Research Project, the skills and abilities peer tutors develop are widely applicable in personal as well as professional contexts. I have absolutely found myself using them in my favorite online spaces as well as in every aspect of my professional life in writing centers.

So: looking back, it’s easy to trace what I brought forward from writing center work into these other venues. But how might these other experiences, especially my transformative fandom experience, speak back again to writing center work?

Validation as Emotional Labor

I’ve been thinking in particular about validation, which I have found absolutely essential in all the spaces I’ve been discussing. I’ve written before about validation and its relationship to belonging, in the context of supporting writers of color at PWIs. Bethany Mannon identifies validation as just one of the many kinds of emotional labor consultants perform; it’s perhaps one of the easiest, though I would posit that it’s one of the most important.

But setting that aside for a moment: Writing Center Studies in general has been turning more and more toward acknowledging emotional labor within writing centers as labor (e.g., Costello; Deges, Nelson, and Weaver; Driscoll and Wells; Harris). While the rewards of this labor do get acknowledged along the way, the focus is often on the underrecognized nature of emotional labor, as well as the costs for those who perform it. This is undoubtedly vital to consider, particularly during an ongoing pandemic, when we have little in our tanks but have been expected to return to some kind of “normal.”

And yet, I find myself asking: does emotional labor, including validation, conform to a sort of first law of thermodynamics? Is there only a fixed amount of energy available—meaning that if we use ours to support someone, we’re taking away from ourselves and giving it to that other person? In other words, is it a pure outlay with no return?

I wonder this because, in the online spaces I engage in for fun, I have enjoyed sending encouraging messages to people looking for support and connection. Maybe it’s selfish, but I suppose I partly do it because I know that when I need support, I can ask for it and receive it. I’ve experienced these interactions in a very “take a penny, leave a penny” manner. In some ways, this does fit the notion of a closed system, where the same support and validation keep circulating.

But haven’t we all experienced consultations where we’ve succeeded in building up a writer’s confidence and derived satisfaction from that experience, leaving both parties feeling energized? Do we ever feel like we get more than we give, but without having taken from someone else? I think so. And so I’ve been starting to wonder: are there less transactional frameworks for understanding emotional labor—at least the ones surrounding projecting and promoting positive emotions rather than managing negative ones?

Gift-Giving and Reciprocity

To that end, I’ve begun to consider what might happen if we adopt or adapt Robin Wall Kimmerer’s ideas about gift-giving and reciprocity from Braiding Sweetgrass to reframe our understanding of emotional labor in writing centers. Gifts necessarily challenge a transactional conception of the world: as Kimmerer puts it, “A gift comes to you through no action of your own, free, having moved toward you without your beckoning. It is not a reward; you cannot earn it, or call it to you, or even deserve it” (23). She cites Lewis Hyde, who articulates how “It is the cardinal difference between gift and commodity exchange that a gift establishes a feeling-bond between two people” (qtd. in Kimmerer 26).

This “feeling-bond,” the relationality, is key, and it is what sets a gift economy apart from a consumerist, capitalist way of understanding the world: “From the viewpoint of a private property economy, the ‘gift’ is deemed to be ‘free’ because we obtain it free of charge, at no cost. But in the gift economy, gifts are not free. The essence of the gift is that it creates a set of relationships. The currency of a gift economy is, at its root, reciprocity” (27). Gifts in this truest sense can only be given or received when relationships are in place or are generated by the gift itself. Gifts can’t be exchanged thoughtlessly; they require actual reciprocal connections.

In the context of writing centers, then, this conception of gifts as embedded in a web of relationships seems to me both appealing and challenging. Often the most satisfying interactions are the ones where we manage to make genuine human connections with writers. This is undoubtedly easiest when we meet with the same person regularly and are able to build an ongoing relationship. It’s more difficult in one-off appointments, of course, but it’s an intriguing sort of challenge to set ourselves.

Validation seems a promising area to focus, as it might be one of the closest things we have to a universal need. Aren’t we all seeking validation of one kind or another, of what we create/write, and of ourselves? The boundaries between those are certainly porous; I’m thinking of Anzaldúa’s statement that “Ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity—I am my language” (81). Isn’t it a gift to ourselves as well as to writers to be able to provide validation, when people come in and share their voices and selves with us?

Please understand: I am not trying to downplay the energy it takes to engage with others in this way.

If your cup is empty, you have nothing to give, and you shouldn’t be expected to give it. As a result of the ongoing COVID pandemic, we’ve all been through sustained and significant trauma, and ignoring it is not helpful to anyone. For many of us, this trauma has left our cups drained. I know mine was, particularly after an usually stressful first half of 2022. I’m only in a place to write this blog post because my experience of finding a welcoming (if imperfect) online community filled my cup back up enough that I could be creative again and do more than the bare minimum again.

So how do we create conditions where people don’t get utterly drained by their work? How do we make the gift economy sustainable in writing centers? How do we fill each other’s cups so we have something to give?

I’m certainly not the only one thinking through these questions; Kristi Murray Costello offers important recommendations about how to help tutors navigate the emotional labor they’ll be asked to perform, as do Dana Driscoll and Jennifer Wells. For me, part of it boils down to naming our experiences and fully acknowledging them. We’re all depleted. There is no “normal” to get back to. Perhaps one of the best lessons we can take forward with us from our ongoing pandemic experiences involves recognizing our limitations, which in turn compels us to consider how to make carework sustainable.

Among all the other strategies we might employ, I believe one of the most important is to tackle our work as a community rather than as individuals. If folks on staff can step up when they have the capacity to do so, then others can step back and recuperate when they need to and give back later if they can. When we acknowledge suffering and evaluate our collective capacities honestly, we can learn how to create conditions in which we can move toward thriving. And I do believe that framing what we do in terms of gift-giving and relationship-building rather than as transactional—the performing of labor with inadequate compensation—may well help in this quest.

And part of what I’ve gained from my online exploits is a potent reminder that we all—administrators, front desk staff, tutors, and writers—are multi-faceted individuals. We are not merely our jobs, nor our academic performance, nor anything else that’s measurable. We must build communities where we can be seen and acknowledged as our full selves, or as much as we want to share with one another. And keeping the fullness of our humanity in mind is vital for considering how even brief one-to-one interactions provide opportunities for connections that can be sustaining, not just draining. Not every time, not in all conditions, but sometimes, and in transformative ways.

Works Cited

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 3rd ed. Aunt Lute Books, 2007.

Costello, Kristi Murray. “Naming and Negotiating the Emotional Labors of Writing Center Tutoring.” Wellness and Care in Writing Center Work. Edited by Genie Nicole Giamo, WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, 2021.

Deges, Sam, Matthew T. Nelson, and Kathleen F. Weaver. “Making Visible the Emotional Labor of Writing Center Work.” The Things We Carry: Strategies for Recognizing and Negotiating Emotional Labor in Writing Program Administration. Edited by Jacob Babb, Kristi Murray Costello, Kate Navickas, and Courtney Adams Wooten, UP of Colorado, 2020, 161-176.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Jennifer Wells. “Tutoring the Whole Person: Supporting Emotional Development in Writers and Tutors.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal vol. 17, no. 3, 2020.

Harris, Nora. Supporting Emotion Work in the Writing Center: Harnessing Shared Investments Between Consultants and Therapeutic Counselors. MA Thesis. University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2021.

Hughes, Bradley, Paula Gillespie, and Harvey Kail. “What they take with them: Findings from the peer writing tutor alumni research project.” The Writing Center Journal vol. 30, no. 2, 2010, pp. 12-46.

Jenkins, David, creator. Our Flag Means Death. HBO Max, 2022.

Kimmerer, Robin. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Kindle ed., Milkweed editions, 2013.

Mannon, Bethany. “Centering the Emotional Labor of Writing Tutors.” The Writing Center Journal vol. 39, nos. 1/2, 2021, pp. 143-168.

Rachel Azima (she/they) is Writing Center Director and Associate Professor of Practice at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. She served as Chair of the Midwest Writing Centers Association Executive Board and is a current At-Large representative on the International Writing Centers Association Executive Board. Their work has recently appeared in the Writing Center Journal and Praxis. Her current collaborative research project with Kelsey Hixson-Bowles and Neil Simpkins focuses on the experiences of leaders of color in writing centers; she is also co-editing a collection of essays, The Reluctant Supervisor, with Katie Levin, Meredith Steck, and Jasmine Kar Tang.