By Leah Pope Parker

Conversations about evidence in writing center pedagogy traditionally focus on the genre of the research paper, where evidence includes the ideas, data, and quotations located through research that must be incorporated effectively into the prose of the paper. However, if we think about evidence more broadly within writing center teaching, as any aspect of writing that claims the authority of truth or expertise in order to achieve the objectives of the written document, then nearly every conference presents an opportunity to talk about evidence. Traditional forms of evidence (such as facts, figures, and the citation of authoritative perspectives) turn up not only in thesis-driven research papers, but also in literature reviews, scientific reports, and resumes. Forms of anecdotal or narrative evidence are also deployed in application essays, cover letters, and personal reflections. Even choices made around primary sources in class assignments that specifically do not call for secondary research can be considered a practice of writing with evidence. Thinking about evidence in all of these modes means that nearly every writing center conference presents us with the opportunity to encourage our students to think critically about their sources and the assumptions that writers and readers make around evidence and truth.

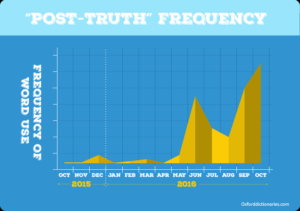

I consider writing with evidence—including both information literacy and the responsible representation of information—to be one of the most valuable skills writing centers can foster in our students. This is especially the case for our undergraduate students, many of whom are just beginning to take an active role in democratic citizenship, as voters listening to and thinking about public discourse. (For the purposes of this blog post, I am thinking primarily about traditional, domestic students at American colleges and universities, though I believe non-traditional and international students have just as much to gain, albeit perhaps in different ways, from consciously practicing writing with evidence.) Public discourse in the United States has lately been saturated with terms such as “alternative facts,” “fake news,” and the “post-truth.” Each of these ideas speaks to questions of evidence: what counts as evidence? what makes evidence convincing? how does evidence produce facts or truth? what evidence are we obligated to believe? and when does evidence compel us to action? I want to suggest that we who teach in writing centers have a unique opportunity to help our students navigate these questions and become responsible democratic citizens, by cultivating our students’ ability to write with evidence.

My goal in this blog post is to share some of the discussions we have had in the UW-Madison Writing Center about the relationship between our mission, our teaching, and changing perspectives on the nature of evidence. Last spring, my incredible collaborator Angela Zito and I co-designed and -led an ongoing education (OGE) workshop on “Writing Center Instruction in ‘Post-Truth’ America.” (In last week’s blog post, Brad Hughes, the Director of the Writing Center and Writing Across the Curriculum, gave an illuminating history of ongoing education in the UW-Madison Writing Center.) Five other tutors joined us to discuss how writing center teaching can respond to a public sphere dominated by “fake news,” informational satire, and social media. We wanted to cultivate strategies for teaching source analysis and evidence-based argumentation that would be conscious of the current political atmosphere of the “post-truth.” Angela and I asked our colleagues: where do “facts,” “evidence,” and “truth” fit into the Writing Center’s mission?

In the collective experience of the OGE participants, few writing assignments explicitly require students to practice critical analysis of their sources beyond what UW-Madison calls Comm A courses. The largest set of Comm A courses at UW-Madison, first-year composition, has a separate English 100 Tutorial Program, so that students in these courses do not use the Writing Center for their composition assignments. However, nearly all of the tutors in the UW-Madison Writing Center have taught or will teach first-year composition, and so we know that a whole unit of the course is typically devoted to informational writing, including a day in the library learning about the library’s resources and information literacy, and assignments ranging from an annotated bibliography to a research paper built on particular kinds of evidence.

Does this mean that students who come to the Writing Center do not need to talk about their use of evidence? Not at all. A core principle of our Writing Center’s teaching is that students at all levels benefit from thinking critically and talking about the choices they are making in their writing. Because students continue to use evidence in their writing, long after their assignments stop specifying information literacy as a target learning outcome, encouraging writers to think about evidence remains a valid teaching strategy for all levels of writers who access the Writing Center. We have the opportunity to ask our students questions directed toward the ethics of writing, using language to represent evidence accurately, and the potential effects of language, all of which are crucial skills for our students—and tutors themselves!—to develop and nurture as we navigate the claims and counterclaims of public discourse.

The participants in the Post-Truth OGE assembled a short list of tools we believe would be helpful for tutors working in a climate of alternative facts. Some of these simply call for the adjustment of training and tools we already have, perhaps even increasing awareness of existing resources, while others offer directions for additional tutor supports yet to be developed. The list of tools as I present it here is deeply indebted to the OGE conversation, with the disclaimer that how I describe these tools reflects my own views, not necessarily those of my co-organizer or the OGE participants.

1. Tutors need support and training for teaching strategies that address students’ use of evidence.

We already invite students to think about their sources when we ask them to articulate their analysis further, perhaps even to the point of reducing the evidence they hope the include. We do this when we ask students to use more detailed description in their application essays. We do this when we ask students to clarify what their data means and how they came by it. We even do this when we direct our students to resources on citation styles.

However, outside of genres like lit reviews and media analyses, we might be forgiven for not inviting our students to think critically about what assumptions they are making by choosing particular sources or particular items of evidence. For example, when students analyze a text assigned for a course, rather than one they found in their own research, it is easy for both writer and writing tutor to take for granted the merits of the source by virtue of it being on the syllabus, without thinking critically about why it is on the syllabus and what life the source held before it was placed on a course calendar. By asking students to assess their own practices of locating and using evidence within such sources, we are cultivating habitual, even self-reflexive, source analysis. We thus teach our students to be more responsible consumers of information outside of the writing conference, the paper, and the classroom. As writing center instructors, we are uniquely positioned to do this kind of teaching across a variety of genres and disciplines, to help students around the university graduate with the ability to more responsibly consume and deploy evidence. In order to do this, though, we need tools for thinking and talking about evidence with our students.

One such tool is this guide to writing with evidence from the Writing Center at the University of North Carolina, which lays out what counts as evidence, strategies for incorporating evidence, and how to determine when one has sufficient evidence. This web page targets explicitly argument-driven essays, but many of its points would also be helpful for teaching more narrative-based forms. UW-Madison’s own Writing Center web site peppers discussion of evidence and sources throughout its Writer’s Handbook, and I can attest to the inclusion of writing with evidence in the way we teach many of our workshops—I have recently taught workshops on literary analysis and on resumes and cover letters, both of which explicitly address the responsible deployment of evidence, but it is not the sole focus of either workshop.

Some ways to improve resources on writing with evidence might include:

- The creation of a handout or poster for use in the Writing Center articulating some core principles for writing with evidence;

- The development of targeted tutor training, in the form of another ongoing education series or part of one of our frequent Least You Should Know staff meetings (in which tutors choose from several options for short workshops or presentations on, as the name suggests, the least they should know about different genres, tutoring practices, or current debates in writing center pedagogy); or even

- The design of a workshop for students on writing with evidence across genres, and how thinking critically about sources and information in a variety of ways can improve one’s writing and one’s overall learning outcomes.

2. Tutors need strategies for conferences in which we feel that a shared assumption of what qualifies as evidence has been undermined, or in which teaching evidence-based argumentation seems to take on a political valence.

Most of our conferences in the last year are not going significantly differently than they would have had they occurred before the 2016 election season—but it is easy to fear that any given conference will. Many college courses, quite laudably, ask our students to engage critically with current events, issues, and debates that are politically divisive, and that means our students are writing claims and arguments that may prompt discord in the context of the writing conference. My personal experience and that of my colleagues attests to this, though for the sake of brevity and both student and tutor privacy, I hope you’ll forgive my choice not to better support that claim with detailed evidence. Suffice it to say that we occasionally find ourselves questioning the validity of evidence—from across the political spectrum—that students believe is infallible. Suggesting that a certain news source might be biased or that an argument may be unfounded can take on political undertones if the perspective the tutor voices aligns with a political pole, even if the tutor does not personally hold that view! In such cases, tutors need strategies for discussing argument effectiveness, without making the writing conference into a political debate, and for returning to the piece of writing if a debate is initiated.

One suggestion that arose from the Post-Truth OGE last spring is that the name “truth” may prove counterproductive here. When we talk to our students about evidence, it is tempting to ask about truth—especially when our political climate sensitizes tutors and students alike to claims of veracity and falsehood. The potential for dissonance in our assumptions about truth carries with it the possibility of mistrust forming between writer and tutor. For the sake of effective teaching and amicable conferences, we might consider framing our questions around coherence, rather than truth. When we notice evidence deployed uncritically, or which we suspect is unfounded, instead of asking whether a student is sure something is true, factual, or accurate, we can ask what the source’s perspective might be, how the source supports this claim, and what assumptions and premises undergird that claim. In this way, ironically, it might be by becoming “post-truth”—that is, by positioning ourselves outside debates of what is true, and instead focusing on what is assumed and what is supported—that writing centers might succeed in addressing the pedagogical needs of the age of alternative facts and post-truth politics.

3. Tutors need a shared teaching philosophy for writing with evidence.

Tutors facing these kinds of instructional challenges need to know where their writing center stands, and where they are permitted to take a stand. As is often the case, one way of assuring tutors of how they can and should talk about evidence is by rooting writing with evidence within the mission of the writing center, to help individual tutors form compatible teaching philosophies. A core part of the UW-Madison Writing Center’s mission is “to support a strong culture of writing across the university.” If encouraging students to think about finding, analyzing, and deploying evidence is considered part of a strong culture of writing, then it is absolutely our responsibility to talk to our students about writing with evidence.

This can be a heavy responsibility, but I also find it empowering. Thinking about writing with evidence across the wide range of genres in which our students work allows us to help our students access reliable sources, analyze them critically, and represent information ethically. These skills carry far beyond the conference and the classroom into lifelong practices of media consumption and the formation of social and political views. When a central feature of a writing center’s mission is to help our students become more responsible consumers of information through the practice of writing with evidence, then we are teaching students to become not only stronger writers, but also more thoughtful, informed, and potentially even more active citizens.

I invite you to share in the comments below your own experiences working with students on writing with evidence, your concerns about post-truth politics as they play out in the writing center, and what strategies you have used when inviting students to more closely critique their sources. Moreover, what resources do you want or need to work with students, on writing with evidence or any other skill, in the age of alternative facts?

Leah – I love this line: “ironically, it might be by becoming “post-truth”—that is, by positioning ourselves outside debates of what is true, and instead focusing on what is assumed and what is supported—that writing centers might succeed in addressing the pedagogical needs of the age of alternative facts and post-truth politics.” This helps me crystallize months’ worth of ruminating over how I want to talk with students about “truth” and “fact” by repositioning truth and fact to be, like writing, continually in the process of being *made* — and being made in dialogue with other people. Thank you for sharing this conversation from our OGE, and for starting a new one here!

Angela — thank you! I’m happy to have helped you crystallize your thoughts. In truth (post-truth?), however, I believe your suggestion in the OGE that we think about a multiplicity of truths led me to think about whether truth can be multiple… and it seems to be precisely the multiplicity of truths (i.e. alternative facts) that puts us in a post-truth world. Moving beyond singular “truth” has its problems and challenges, to be sure, but only if we and our students do not learn to navigate these many “truths.” So if this is the world we live in, I hope Writing Center teaching can keep up, to continue cultivating those valuable information literacy skills.

I agree with Angela too. Perfect line!

Thanks for delving into this difficult but important topic, Leah. You’ve helped clarify many of the concerns I’ve been pondering this past year. I find tool #2 particularly resonant. There have definitely been times I’ve been concerned that “suggesting that a certain news source might be biased or that an argument may be unfounded can take on political undertones.”

Relatedly, I wonder if we should continue to reevaluate not only the politicization of truth in Writing Center teaching, but the political work of the Writing Center appointment itself. How do we understand the politics of WC teaching as similar to or different from the politics of classroom teaching? As a writing instructor, am I positioning myself as a “neutral” third party, and what does this mean?

Erica, thank you for your comment. You’ve touched upon something I, too, have been pondering: how does one’s teaching persona in the classroom differ from one’s teaching persona in a writing conference? I find that I am more comfortable being a real human person with real opinions about the world in one-on-one conferences, whether related to my classroom teaching or in the Writing Center, because it’s easier to gauge interest and relevance with only one student. In both cases, I think meta-language about evidence-based analysis might help us worry less about politicizing ourselves, by presenting the skill of evidence-based argumentation as apolitical. I don’t think we can generally expect to dramatically change our students’ worldviews in as little as half an hour, but we can help them in the direction of thinking critically about evidence. And I would say the cultivation of that skill is beneficial for democracy on the whole, regardless of how students choose to use the skill. Does that make the act of teaching evidence-based argumentation political? I suppose so. But I don’t think the skill itself is necessarily polarized, and it might be more effective to teach it as unattached to any particular political objective.

Leah, I appreciate being let into some of the mental work surrounding this OGE. Blogging about some of the ideas that your conversations generated is a great way to expand the boundaries of that particular professional development opportunity!

I have a thought about resources and a thought about dissonance.

Resources: This summer on the UW-Madison Writing Center’s Online Handbook a new page went live entitled “Revising an Argumentative Paper.” One of the tips for revision involves outlining argumentative claims and evidence in order to consider the strength of the argument. I wonder what you think about that kind of resource as a model that could be expanded on to more specifically consider evidence . . .

Dissonance: You mention that “the potential for dissonance in our assumptions about truth carries with it the possibility of mistrust forming between writer and tutor.” I’ve recently been reading a lot of compositional scholarship that suggests that experiences of dissonance can be productive for motivating revision, but I think you make a very important point here. En route to encouraging writers towards revision, dissonance can also do some pretty serious relational damage.

Thank you for sharing these thoughts, Matthew!

Re: resources. As with all of the other new pages in the Writer’s Handbook, “Revising an Argumentative Paper” is an incredible resource! A lot of the points in that list already encourage thinking critically about evidence, especially thinking about assumptions and looking for dissonance. I wonder if a step that could be taken after outlining claims and evidence might be to look specifically at the evidence for what the source is, how else it might be interpreted, and what assumptions the source makes. If we were to add to this page, perhaps a numbered point (between 2 and 3 or 3 and 4?) along the lines of “Reassess your evidence” might get writers thinking specifically about their evidence as evidence, not just as it relates to their argument.

And re: dissonance. That’s a really great point. I think where dissonance is productive might all come down to rapport. I can think of several situations, where I have set myself up as the skeptic that a student needs to persuade, and they’ve taken that as a challenge and written a stronger essay because of it. Of course, I don’t think any of these were more fraught topics than “I’m not sure I agree with your reading of this passage” or “I’m not convinced this was the best way to run this experiment.” In theory, though, if a tutor and student are getting along, I could see such a move working with a more politically charged topic, but it might be more successful with the removing gesture of “Pretend I’m [opposing political group]. What kinds of arguments am I going to make against your claim?” — this seems to be very similar to what the advice about “looking for dissonance” is doing in the new “Revising an Argumentative Paper” section of the Handbook. However, if the tutor becomes defensive or seems to be hostile to the student’s possibly deeply-held views, that’s where I see dissonance becoming potentially harmful.

Such a relevant and smart post, Leah! I particularly like your engagement with evidence in genres we don’t necessarily see as evidence-based. I find myself often using the word “evidence” in discussing genres like resumes, personal statements, and the like, but I had not really considered how the labeling of elements in these genres AS evidence suggests a certain connection to “truth.”

In my new position at a tech school, I find myself addressing the subject of evidence in slightly different ways. Evidence, for many of the students I see both in my first year writing classroom and in the CommLab (Georgia Tech’s multimodal writing center) view evidence as something very specific: as scientists and engineers, the results of experiments, processes, or equations or often statistics are what they find convincing evidence. So I’m often shifting their world view when I call, for example, their past work experience “evidence” on their resume. This post suggests that perhaps finding a language to talk about this evidence in the terms of scientific evidence could help me both build rapport and, if I step back and ask them to look at what I’ve done critically, encourage them to interrogate their own views of truth. In my short time here, I have seen the necessity of providing these smart students who will be coding our software and making our spaceships with opportunities for this kind of humanities-oriented critical thinking, to show them that even code or machinery makes assumptions and is rhetorically positioned. Thanks for adding to the toolkit.

Thanks for a terrific post, Leah! I very much look forward to using this post as a foundation when I begin my position as a writing center leader in December.

I particularly appreciate the movement between points two and three. In the discussions I’ve seen around pedagogy and the “post-truth” moment at other institutions, I often see instructors tying themselves in knots trying not to seem “overly political” when addressing a question that can’t help but be just that. I understand why, but avoiding the underlying reason for the entire conversation, we avoid so many of the questions (and situations) that make it so challenging. At the same time, number three underscores the need for a response that isn’t purely political. As you say, we need a response grounded in theories that transcend this particular moment, and these particular public figures. Otherwise, the ground beneath our arguments threatens to move with the political landscape.