By Annette Vee

Like every other teacher in higher education right now, I’m navigating the new terrain of socially distanced, online, hybrid or hyflex teaching due to our global pandemic. I’m also a writing program administrator, which means that I share some responsibility to help other teachers navigate this terrain as well. Conscious of the labor issues of instructors preparing new classes in flex, hybrid or online contexts, I’m digging into my online toolbox to share strategies that might work for others in this context and for the future, after the pandemic. The best little tool I have for teaching online or in hybrid formats is a class blog. Blogs can provide a space for students in any course to write through ideas in a low-stakes context and connect with each other, which is especially salient in a time of strained communications.

Teaching online requires new technologies, methods and approaches that are Personal, Accessible, Responsive, and Strategic, as Borgman and McArdle describe. A class blog can help instructors to hit all of those goals without requiring students to learn yet another fancy proprietary platform, and fostering student-student interaction may help to mitigate some of the isolation that students felt in the spring when their courses went online. While a well-run class blog isn’t a substitute for in-person discussion, it does much of the same work: blogs can give students time to chew on ideas, exchange them, and bring in their own experiences, with the added benefit of writing practice and space for reflection. Low-stakes writing activities boost engagement and learning (thank you, Peter Elbow), and blogs can serve to make writing a shared habit and space of exchange in a class. The ideas that students generate in blogs can provide concrete directions for discussions of more formal projects in Writing Center appointments. For students who are less comfortable in the extemporaneous speaking environment of the face-to-face classroom, blogs can be a great way to engage with ideas and peers without the same time pressures, so they can serve as means of balancing class discussions and giving more students a place to make their voice heard.

Providing an online way of extending class discussion, without some of the challenges of face-to-face encounters, is also one Universal Design “place to start” that Jay Dolmage describes to unmake ableist classrooms. Blogs help further a commitment to accessible teaching if we acknowledge, as Aimi Hamraie asks us to, that it has been crip technoscience and disabled ingenuity that imbued them with much of their possibility as critical digital pedagogy (thank you, Leah Piepzna-Samarasinha, Aimi Hamraie, and Kelly Fritsch).

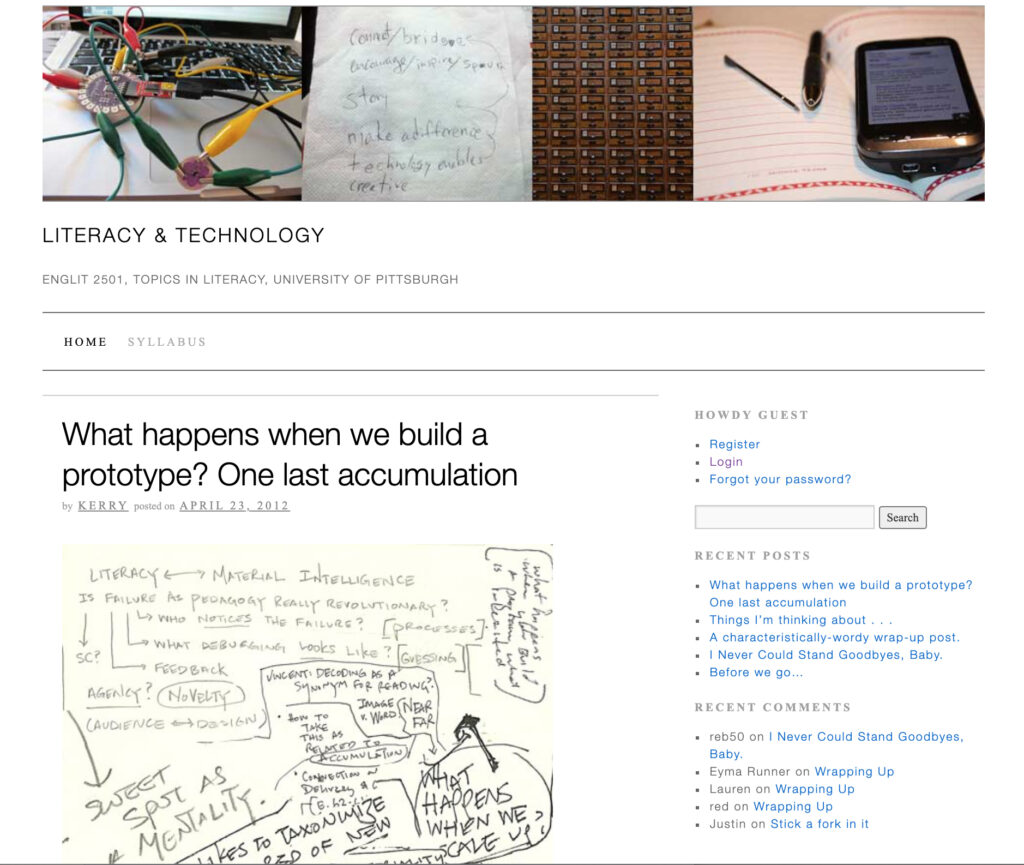

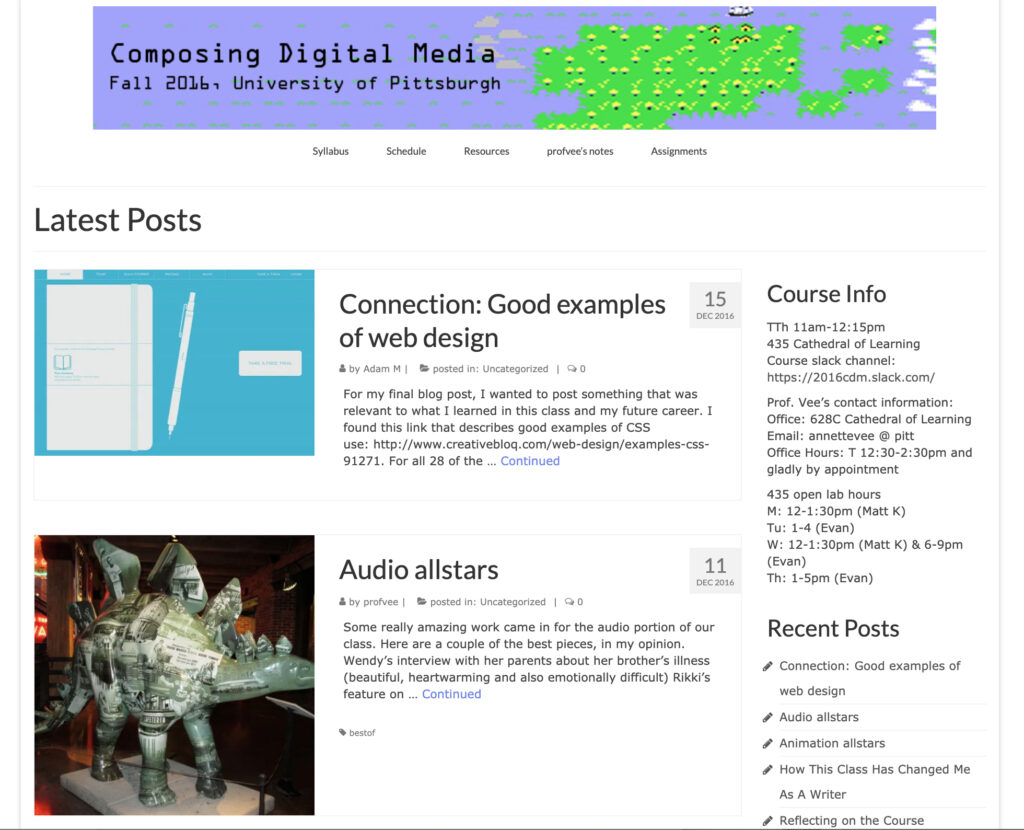

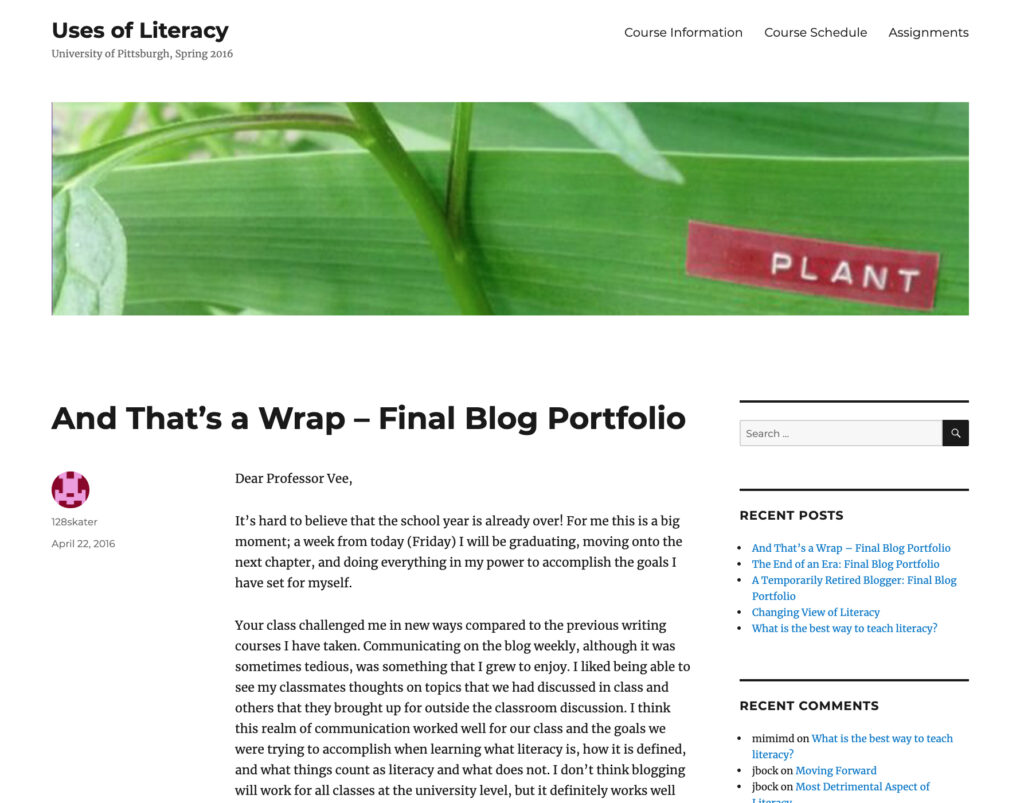

I’ve taught with blogs since 2004, first as a graduate student in the composition and rhetoric program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, then as a college writing teacher and administrator at the University of Pittsburgh. The flexible format of blogs has enabled me to use them successfully in undergraduate general education courses from first-year writing to upper-level writing, philosophy and computing courses and in graduate classes on pedagogy, literacy, and technology. After years of trial and error, I now use the same basic blog format for every class, which helps my students and me to make the most out of the class blog while keeping the workload manageable for all of us. My prompt is open, and the same every week: write a 250-word post on ideas or readings from the class or a 150-word comment extending those ideas. Each week, two groups of students trade off posting or commenting. I read the blogs weekly, highlighting especially good observations in class discussion, and noting what students get (and don’t get) from the material for the week so that I can adapt to their interests and needs. Assessment is essentially non-evaluative–crucial for managing workload for both students and instructors–and accomplished through a portfolio or checkmarks for completion. This format helps students grapple with course concepts using low-stakes writing for an authentic audience, fosters class community, and helps me respond to their uptake of the material.

My model is not perfect (teaching never is!). There are questions of student and faculty labor in writing and reading new formats and dangers of breached privacy, for instance, which I address below. Just like any other teaching technology, blogs are not autonomous or automatically successful. There are plenty of examples of how blogs can be used poorly, and I won’t belabor them here. Instead, I’ll share some guidelines that may point toward a greater chance of teaching and learning success, which I hope you might find useful in the courses you teach across the curriculum.

Start with good pedagogy

As with any approach to teaching, the first step is to consider questions of learning objectives: what do you want students to accomplish in this format? How will you set up blog interactions to meet those goals? How will you communicate your expectations for students, and how will you remain sensitive to their needs and ideas? Our students may be especially open to new methods of teaching out of necessity during the pandemic, but they are also experiencing trauma from many different vectors. Even tried-and-true pedagogies will require flexibility and careful listening. Be willing to listen, learn and adjust your approach. And of course, begin with kindness.

In Teaching Queer, Stacey Waite describes underestimating a student who appeared disengaged in class discussions and then reevaluating her judgment after talking with him. She wonders: how many students have I underestimated? I’ve also had students who, had I judged their engagement only on participation in class discussions, would have appeared disinvested–yet online, they are thoughtful, brilliant and creative. Like Waite, I wonder: how many quiet students do we overlook because the format of a course doesn’t allow them to find types of interaction that are meaningful to them? Providing an alternative format such as a blog can allow more students to find and show their strengths.

Disability and accessibility advocates have long made similar observations about the need for multiple formats and flexible ways of engaging. Resources compiled by Jay Dolmage, Aimi Hamraie, Christina Cedillo, Ai Binh T. Ho, et al., and Tara Wood, et al. may be particularly useful in thinking through the intersection of disability, pedagogy, and the new terrain of online/hybrid teaching. Especially if synchronous class discussions are conducted over video conferencing, where performance pressures and anxiety about relations appear to be heightened, blogs provide students another way to freely engage with course material.

Synchronous discussions can help students grapple with ideas, too, but the time and performance pressures of the virtual or physical classroom means that this format won’t work for all students. Students with anxiety, hearing disabilities, reticence in social settings, spatial learning styles, or a need for more time to process material may find not a lively face-to-face discussion beneficial to their learning, especially when this discussion is conducted through videoconferencing. Blogs don’t work for all students, either: students with organization or planning challenges, or writing anxieties can find them challenging. But the students who thrive in synchronous discussions are often disproportionately rewarded over students who require more processing time or who are less comfortable in this sometimes agonistic space. Blogs provide a forum for students to write on their own time and engage with their peers outside of these pressures. Students who thrive in synchronous discussions can also benefit from taking time to process, write, reflect, and consider their peers’ ideas before introducing their own. Perhaps the greatest advantage of blogs is that they enable an asynchronous mode of interaction among students about ideas in a course.

Blogs also enable students to engage with course material in a space that is less mediated by an instructor’s agenda. I ask students to choose their own angle of engagement in blogs (see below), and by reading their ideas prior to synchronous discussions, I can better understand where they’re coming from–what they got from the readings, what they missed, what was most interesting to them. Even with material I’ve taught a dozen times, I am consistently surprised and delighted with what students find (and don’t find) in assigned material. Reading their thoughts without me kicking off the conversation allows me to stay fresh and open to this particular group of students’ interpretations and investments and then tailor my approach to their specific needs.

Providing an online space where students control the topics of discussion is a leap of faith. It requires students to respect each other in discourse–which instructors can encourage through course policies and modeling–but it also requires instructors to let go of at least part of the narrative of a course. Especially in graduate and upper level undergraduate courses, I have found that students often get comfortable enough to push back on readings, the course, and even their peers’ ideas or my framing of material. They also support each other in novel ways, offering similar experiences and concerns or references and links for further exploration. They write more for each other than me; their writing is less transactional (given to someone in exchange for credit) and more actionable (created with purpose and designed to achieve a goal), as Chris Friend advocates. Through this peer feedback–both the critical engagement and support statements–blogs can help students feel heard. By learning more about their peers’ interests and experiences in blogs, students often tell me they feel a stronger sense of classroom community and attachment to the course. In a socially distanced, online, hybrid or hyflex teaching environment, especially in a time of significant stress for students, these connections may prove vital for student engagement, retention and learning.

Blogs can provide frequent, low-stakes writing assignments and rapid feedback loops among students if they are well-implemented. They can also be fodder for more complex assignments. To maximize these benefits, I recommend that blog assignments ask for thoughtful but not fully revised writing; posts with a regular rhythm throughout the semester; frequent commenting from peers; and assessment that emphasizes completion or reflection over qualitative evaluation from the instructor. Implemented poorly, blogs can feel like busywork to students and time-sinks to instructors. As with any pedagogy, the devil is in the details. What does good pedagogy look like with blogs? Let’s see.

Tips for using blogs in your course

- Consider some potential goals of blogs and decide what’s important for your class: balance voices in a course, enable multiple modes of engagement, allow students to consider course material with less mediation from you, and give students practice with low-stakes writing. Which goals are more important to you?

- Decide what blogs will be replacing from your previous course design. Given their workload, blogs should not be added onto an already-existing course workload; instead, they might be swapped out for other assignments or class activities.

- Use your university’s Content Management System (CMS) if you’re trying out blogging for the first time. Any major CMS (including Desire2Learn, Blackboard, Moodle, and to a lesser extent, Canvas) has a workable option for student blogs. The advantages of using a CMS-based blog are: campus IT support and documentation to help you set them up; a private platform; student familiarity with the platform; and streamlined assessment and accountability to make your life and theirs a bit easier.

- Tell students why you’re using blogs in the course, how this will benefit them, what your expectations are, how they will get credit and be assessed for their work, and how their blog writing will interact with other aspects of the course. They may have experienced blogs in other courses, and may not have found them valuable: show them how blogs will be an integral part of your course at the beginning of the semester and throughout.

- Establish a regular and dependable rhythm for blogging and commenting, and allow for flexibility in that rhythm. Blogs should be an ongoing conversation, repeated throughout the semester, so that their process is iterative.

- Make expectations clear for when students should post and comment. You could split them into two groups and have them switch off posting or commenting each week (which can work well for writing classes), or have them sign up to post on particular weeks of interest to them (which can work well in content-focused classes), or have them do five comments by midterm, etc. Whichever format you choose, let students know and then follow up to help them learn the rhythm.

- Provide guidelines and models of good posts early on. Especially in undergraduate courses, word count guidelines can be useful to help students understand what level of engagement you’re looking for (e.g., at least 250 words for a post and 100 for a comment). Models of good posts or conversations can be highlighted in class discussion, starred or brought forward on the blog itself, or shared via email.

- Let students bring in their own ideas for the blog. You can set up expectations, but avoid writing detailed blog “prompts.” Writing detailed weekly prompts not only requires you to do more work, but it also curtails student expression, engagement, and community-formation.

- Don’t treat blogs as mini-essays to be revised. While posts may be used as generative, raw material for later assignments in the course, asking for revisions of posts can detract from blogs as a low-stakes space for circulating and writing through ideas. I prefer to treat blogs as one-and-done. If you want students to revisit their blog writing, portfolio assessment is one great way to do so.

- Give students the option of emailing you directly instead of blogging online, no questions asked. To further protect student privacy, encourage students to keep their conversations within the class by discussing class confidentiality.

- Let them know you’re reading their blogs in supportive ways: refer to ideas from the blogs in conversation with students individually or in class discussion; help students see connections between their own ideas and the ideas of their peers; quote particular posts in your written communication to students; or comment occasionally in nonevaluative ways on blog posts. Avoiding regular evaluation is key to managing your own workload and supporting peer connections and independent writing on the blog.

- Give students credit for their work: count it as part of the work for the class in a low-stakes way, though avoid too much evaluative credit. You can give credit on a check-mark basis, contract grading, or blog portfolio that asks them to do the metacognitive reflective work on their own writing.

Setting up blogs

To set up your expectations for the blogs, first think carefully about what role you want them to play in your course, and what you want students to learn from doing them. Some questions to ask yourself:

- How much time and energy do you have to invest in the design, implementation, and feedback loop for the blogs?

- What will blogs be replacing from your previous course design?

- Will students blog on your closed CMS or in a public space like WordPress.com?

- What rhythm will you employ for the blogs? How many times do you want students to write or comment and at what pace during the semester?

- How will you foster engagement between students, and how involved do you want to be in that engagement?

- How will you communicate the value of blogs for the course in your setup as well as throughout the semester?

- How will you respond and give students credit for their work in the blogs?

In the rest of this section, I provide some guidance to help you consider your answer to those questions and elaborate on the tips provided above.

Time investment

How much time can you allot to this work each week or throughout the semester? Hybrid teaching is frankly more work than using only one modality, partly because of task-switching between online and in-person interactions. And online teaching can feel “always on.” Be honest about the time investment necessary for even a simple format change for the course, and then consider your own comfort level and technological skills in your time calculations. Consider factors such as student enrollment numbers, course level, and whether you are co-teaching or have the help of a TA. Depending on all of these factors, your time investment may be one to four hours per week. There are diminishing returns beyond four hours, regardless of your course format.

To do blogs well, you will need to tend to them regularly. You can think of them like a garden: they require cultivation and attention for the best yield. If you plant them in good soil and allow them to establish roots, you can step back for a week or two and let them grow, but they still need regular attention throughout the semester. As you consider your time investment, make sure to give both yourself and your students flexibility to take a week or two off when necessary. Don’t require yourself to respond to every blog post, or give feedback every week, or you will be overwhelmed and students will begin to write for you rather than each other.

I spend a lot of time establishing expectations in the beginning of the semester, outlining the rhythm of blog posts and comments and assigning students to different weeks or blogging groups. Some students inevitably have some technical issues in registering, logging on, or posting, and so in the first two weeks I offer tech support. My first prompt for blogs is an easy “introduce yourself.” Once every student has blogged and commented once, this support is no longer necessary. I can then focus my time on reading the blogs and planning on how to integrate their observations in synchronous discussions. As long as you engage with them regularly, blogs allow flexibility for your own schedule; some weeks I don’t even have time to read posts before class, and others I’ve read them thoroughly and found ways to engage with them actively. But every week, with the format that I use, some students have read and responded to each other, and so the blog is still “tended to” when I’m away.

Managing student expectations

Managing student expectations is a critical aspect of hybrid course design, and blogs are no exception. In her survey of students in hybrid courses, Patricia Webb Boyd found that students often perceived the online portion of the course as “busywork” or otherwise did not understand how the online portion of the course fit into the more traditional f2f portion of the course. Students were less likely to question the goals of f2f class discussion or traditional coursework such as essays, and seemed to judge the online portion of the course through a paradigm of traditional courses, according to Webb Boyd.

Perhaps this phenomenon will disappear as students encounter more hybridity in their courses; however, I have still seen that students need more justification for blogs than for “traditional” work like essays or exams in college courses. In designing aspects of hybrid courses such as blogs, then, “[w]e need to include a focus on teaching students to effectively interact online and to ‘read’ the online course environment in order to determine the pedagogical goals” (Webb Boyd, p. 234). Students may expect online components in their courses during the pandemic, but their ideas of what that looks like may be vague or affected by previous negative experiences. Clear communication about pedagogical goals in the course, and how blogs help students to meet those goals, is critical.

Reading course evaluations and from surveys I’ve given to students about blogs in my courses, I occasionally see students complain about the busywork aspect of blogs in a class. I take this as a signal that I’ve not set them up properly or helped them to see the benefit. It may also be a sign of their commitment to the class: I found this critique to be sharpest in a required graduate class I recently taught, which told me that it was also a reflection of some students’ investment in the class generally, and an issue with the course deeper than blogging. Usually, most undergraduate and graduate students describe the blog as an enjoyable learning and community experience.

Below is an excerpt from a syllabus for a first-year writing course focused on “Technology and Culture in Pittsburgh” where I set up my expectations for the blog. In this course, I used a public instantiation of WordPress as a platform and hosted it on my personal website. I assessed the blogs through a final blog portfolio, worth 15% of their final grade. I also had the benefit of an undergraduate TA who read the posts regularly and followed up with students whose participation was lagging. Blog-reading and commenting is a great way for a UTA to participate in non-evaluative feedback for students. When I don’t have a TA (which is most of the time), I simply do that feedback myself. I supplemented this syllabus description with in-class discussions about public participation online and a more detailed assignment sheet for the blog portfolio.

SampleBlogDescriptionUGradCourseSyllabusConsider blog platforms

When blogs are introduced to the course, students are also owed an explanation about the platforms they are required to use so that they are aware of some of the rhetorical and pedagogical goals behind these choices. So take some time to review your options in terms of your technological abilities or available support, students’ access, and your goals for the blogs.

If you’re diving into blogs for the first time, your university CMS is likely to be your best choice. The advantages of using a CMS-based blog are: IT support and documentation to help you set them up; a private platform; a more consistent location for students to access course resources (provided you are using the CMS for grades or to distribute readings, etc.); student familiarity with the platform; and streamlined assessment and accountability to make your life a bit easier. Students often expect a class to be run through their CMS, and they already interact with it for other classes. Using the CMS, then, helps to manage student expectations and workload. Be aware that students may have had previous experiences with blogs on the CMS that were not well supported by the instructor, and you may have to change that narrative for them at the outset and continue throughout the semester to demonstrate how blogs in your class are different.

The two reasons you might consider asking students to blog outside a CMS are 1) to give them practice with the responsibilities of writing in public and 2) to provide experience with a platform they might use in professional contexts. This approach generally requires instructors to have more technical skills and to provide their own IT support for students, as well as attention to what they are writing in public. When I use blogs, I generally use WordPress on my personal website. WordPress.com is also a good, free choice and does not require significant technical skills or ownership of a web domain. Students have written to me after courses to say they found it professionally useful to know WordPress, and in surveys I’ve given comparing CMS and WordPress blogs, they often report that WordPress has a nicer interface and more enjoyable interactions through its commenting features. But there are some ethical issues in asking students to blog on a course site that I host personally or that is hosted by a third party, and it can be confusing to students to have the course blog located outside the university CMS.

Privacy, anonymity, and opting out

Questions of privacy and anonymity are mitigated somewhat if students are blogging on a CMS, and therefore having their writing shared only among the class. In that case, setting up classroom expectations of respect are not much different in online discussions than in synchronous discussions. Still, I would recommend making these expectations explicit for the blog. To foster trust among students, tell them directly: conversations in person or online should not be shared outside the class, especially on social media.

In WordPress, I’ve always had students blog pseudonymously or using their chosen/first names only, so that their online writing is not connected to their real or full names. This privacy measure is critical to protect students. I’ve alternately had students know who everyone is on the blog and not know each others’ pseudonyms. In (IRB-approved) surveys I gave for the private pseudonyms in a 19-person writing class, some students reported loving the chance to interact without knowing who was writing because they could be more “free” or simply engage with ideas presented by classmates with fewer interpersonal tensions. Using a CMS is likely to restrict the option of private pseudonyms or anonymity, however, and without the risks of writing in public, the advantages of doing so are few.

Because I’ve asked students to blog in public, I’ve always given them a chance to “opt-out.” In those cases, students simply email me their posts privately. For commenting, I ask them to email both me and the original poster, if they’re comfortable doing so. I do not ask why they’re opting-out, but some students provide reasons to me anyway: they have anxiety, a stalker online, bad history with another student in the class. I take these proffered reasons as reminders to be compassionate and flexible about the complexity of students’ lives, in blogs and in every other part of my course. Even on a CMS, I would recommend giving a no-questions-asked opt-out alternative to students. You never know.

Guidelines for posts and comments

Key to successful blogs in a course is establishing a regular rhythm of posting and commenting. This regular rhythm substitutes for revision, as blogs work through iteration rather than revision. Students should post no fewer than five times during a term in order to get comfortable in the space. Each post is a new start, a new attempt to work through the genre by thinking through ideas in the course. As in class discussions, students establish a rapport with each other through their regular exchanges. The regularity of a blog schedule helps to support a good writing habit, and can contribute to the clarity necessary to establish in online courses.

A back and forth rhythm is also important to successful blogs. I generally assign my undergraduate students to two groups; each group alternates posting and commenting. Because the two groups are on opposite schedules, posts and comments are happening every week on the blog. In graduate classes, I have them sign up for particular weeks that pique their interest and I ask them to comment on the other weeks. I ask for fewer posts from grad students because their posts tend to be longer and more engaged.

Consider when during the week or when during the semester blog posts will be due. I find it helpful to have blog posts due every Monday at midnight for a Tuesday class so that I can use them to prepare for class. Sometimes I have comments due at the same time as posts, which gives students more opportunities to engage before we consider course material together. Having everything due the same day of the week, every week, helps to streamline the schedule and allows students to manage workload better. They miss fewer comments this way. But having comments due later in the week allows for slightly-late posts to get comments, too, and enables a better synthesis between in-class and blog discourse.

In my experience, students are more inclined to see the comment week as their “off” week, and so they tend to miss comments more than posts. To help students to understand the importance of commenting to the conversation, I point to great comments and interactions in class discussions. I note that it often feels better to write for an audience, and getting comments tells us that someone is reading, that they’re not writing into the void. Students will sometimes support this framing: they appreciate comments from their peers, and in discussion, will sometimes refer to meaningful exchanges and specific ideas from their peers. These moments help students feel heard and encourage deeper engagement with the course and each other.

A regular rhythm in blogs should allow for flexibility: everyone has off-weeks, including the instructor. Some weeks I just can’t read the blogs, or students post too late to be helpful for structuring discussion. As I mentioned above, the blog rhythm should allow for some variation: students missing a week and posting twice the next, posting late, missing comments, etc. This flexibility accords with “crip time” approaches to teaching and deadlines–that is, providing flexibility in deadlines, recognizing variances in rhythms, and going with that flow, in tune with Margaret Price’s descriptions of crip time in school and as Tara Wood recommends in “Cripping Time in the Composition Classroom.” I don’t penalize students for getting out of step, as long as they are engaging regularly. Some students have difficulty engaging regularly with the blog, and when that happens, I follow up with them individually to see why. I give them alternative schedules, let them make up posts or comments, or otherwise try to work with them so that they can contribute. Especially now, allowing space for flexibility and care is important.

The first week, I have everyone post an introductory hello and comment on a peer’s hello in order to help me learn more about their interest in the class, dive in to the blog, and work out any technical difficulties. There are always some technical difficulties! Plus, students enroll in the class late, or forget, or don’t understand the assignment. Beginning with an easy, low-stakes post and comment prompt helps us all begin to get comfortable in the space.

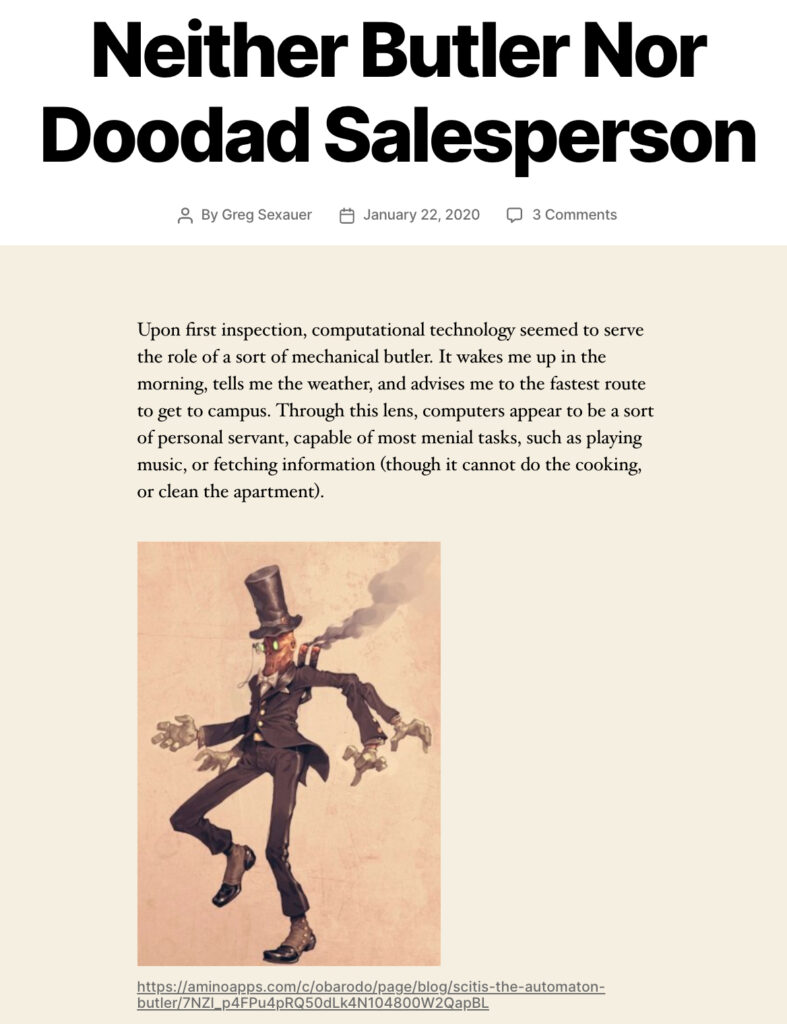

In my writing courses, I don’t provide prompts for the posts for the rest of the semester. Letting students choose their own topics of engagement is beneficial in a few different ways. Foremost, it gives them an opportunity to engage with course material in a less-mediated space, more on their own terms. At the public research universities where I’ve taught (including UW-Madison), students are often good at responding to instructors, answering questions, and following directions. Finding their own way into material for a course is often harder for these students, but it’s beneficial for their learning of content and metacognitive skills. As they get used to following their own interests, they generally become more comfortable choosing their own angles into the material. In the process, they learn more about each other and themselves. Not providing prompts for the posts is also helpful to me as an instructor because it’s less work for me and also helps me to see how they want to engage with course material.

A course I co-teach on the role of the digital in human life (which fills the philosophy and ethics general education requirement at University of Pittsburgh, where I teach) is more content-focused than my writing courses, and so in that course we assign weekly prompts. These prompts ask students to engage in different modalities of expression–video, drawing, images, audio, text–and connect their personal experience to critical issues in the course such as augmentation, gender, and education technology. Because the prompts require personal connections, we can reuse these prompts each time we teach the course, pruning the less successful ones and adding new ones as we go.

Engagement and assessment

I try to align my assessment of students’ work on the blogs with the goals that I want them to accomplish: regular writing habits; engagement with course material and each other; the metacognitive work of seeing their own engagements and writing in context. I acknowledge their collective engagement by pointing to their observations in synchronous discussions or conferences. They know I’m reading their work regularly. In my writing courses, I don’t provide a qualitative evaluation of their individual blog posts because the individual posts don’t stand alone, unlike essays or other assignments. I acknowledge posts with a check-mark, or I have students assemble a portfolio–sometimes both a midterm and a final portfolio–of their best posts and comments which asks them to reflect on their own work.

In this portfolio, students determine themselves what “best” means, and describe why they think the particular posts they include are their “best.” Their determination is generally shaped by our conversations in the class about engagement with ideas and each other, but sometimes they surprise me with their “best” posts–those that are most personal, the best articulation of an idea they’ve been thinking about for a while, a post with the most unrealized potential. Establishing their own criteria for “best” is part of the meta-cognitive work students can do with blogs.

Because I value regular engagement, I set up a spreadsheet in which I mark the completion of their weekly posts and comments. As with my attendance record, I simply mark yes or no. If their posts are late, I might note that. But I don’t sweat it if they have a few late posts or comments. The spreadsheet helps me to see if a student misses a few weeks in a row or if a pattern emerges that we should discuss.

SampleBlogPortfolioAssessmentUGradCourseSyllabusIn my undergraduate digital philosophy and ethics course, I respond weekly to individual blog posts at the rate of about five students per week. I assess the posts and comments at midterm and at the end of the class. Using a spreadsheet, I keep track of when I respond to students so that they all hear from me at least twice during the term. This high-enrollment course also has TAs who offer non-evaluative and regular comments each week, and students post on each other’s writing, so students know their posts are being read regularly. My co-teacher and I ask the TAs to “check-mark” the posts and comments and let us know when a student needs a follow up.

Different modes of assessment require different time investments for the instructor and the student. I’ve found the “check-mark” method to be on the low end, and the portfolio assessment on the higher end. For graduate students, I just use the check-mark method, but I give them informal formative feedback through conferences and in-class discussion, and I write them a long comment at the end of the term about their contributions to the course, both in-person and online. This feedback is generally more meaningful to graduate students than grades. I will often do this kind of cumulative response to contributions in undergraduate writing classes as well, though my comments are shorter because the enrollment numbers are usually higher.

Caveats

Although I believe I’ve found a good approach to teaching with blogs in my courses, it’s not perfect. I tweak it every semester. And I recognize that there are persistent issues with implementing blogs in a course, that I’m glossing over details, and that your mileage may vary.

The most prominent issue for teaching in the context of the pandemic is the fact that so many of us are asked to revamp our courses without compensation for that work, or have uncertain contracts, and may face pay cuts. As a writing program administrator in this current learning context, I don’t have direct control over compensation. But in providing this resource on one approach that could work for socially distanced, hybrid, hyflex or online classes, I hope to help lighten the workload just a bit for faculty preparing their courses in this context–and beyond.

Putting aside the significant issues of workload and compensation, I believe this is a moment for us all to examine the ruts in our teaching and look to new ways to integrate digital technologies productively. Rather than waiting for administrators to dictate teaching modes and styles, instructors can consider questions about student engagement and outcomes in hybrid courses, Catherine Gouge points out that if we do not, “we may inadvertently forfeit the opportunity and the power to debate the design of a curriculum that might serve as the foundation for a major shift in the face of campus-based writing programs.” She describes the new shift to hybrid education, which differs from the fear of writing teachers in the early 1990s that the teacher would become obsolete, or the Khan Academy vision of the entirely self-directed learner. Hybrid courses have the potential to engage students typically disengaged from face-to-face formats, to enact more “active learning principles” in learner-centered education, Patricia Webb-Boyd notes, and to distribute instructor knowledge and work more widely, Gouge argues. At least they have the potential to do so.

Blogging adds a technological dimension to a course and can increase instructor workload, especially on the front end of a course, and for instructors using blogs for the first time. Instructors need to become familiar with their blogging platform of choice, help students get set up on that platform, and recognize technical issues as they arise. The university’s IT or teaching center can support this work in some cases, and it does ease up as the semester goes on and in subsequent semesters. I have described my ways of framing the rhetorical affordances of blogs in my class and engaging with students in this medium. You’ll find your own.

Mode-switching between online and face-to-face formats in hybrid or hyflex courses can feel exhausting for both students and instructors. But new modes afford new circulation patterns and practices. Blogs don’t work for all students. But neither do traditional face-to-face modes in interaction. Offering multiple modes of interaction is frankly more work, but it is time well spent.

Despite these issues with blogging, or with hybrid formats generally, I remain convinced that college instructors can successfully implement blogs in their classrooms—carefully, critically, responsibly, so that students can do the same when they write in online public spaces. And when students do write carefully, critically, and responsibly in online spaces, they may be able to reap the benefits of more widely circulated ideas, more diverse personal networks, and greater facility with the many communicative options now open to them.

Creative Commons CC-NC-BY license. You are welcome to use and adapt any part of the materials provided here in non-commercial settings, provided credit is given to the author, Annette Vee.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Greg Downey, whom I TA’d for in Fall 2008 at the UW-Madison for an innovative hybrid course, “The Information Society”; Sean Stewart, a UW-Madison student I talked about these ideas with in 2008-2009 and subsequently lost track of; Mike Shapiro, who has been an interlocutor for digital pedagogy for over 15 years and first introduced me to using blogs in writing classrooms when we were both UW-Madison graduate students; friends and colleagues Stephanie Kerschbaum and Tim Laquintano (also fellow UW-Madison grads) as well as Marylou Gramm (my colleague at University of Pittsburgh), who offered helpful comments on this piece; co-designer and co-teacher of the Digital Humanity course, Alison Langmead; all of the students who have written for blogs in my classes, and especially those who gave me feedback on their impressions of blogs in my courses through conversations, surveys and course evaluations. And a big thank you to Jennifer Conrad and Emily Hall for accepting and stewarding this piece for Another Word. A version of this work was published on Inside Higher Education.

Annette Vee is Director of Composition and Associate Professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh where she teaches both undergraduate and graduate courses in textual and digital composition. She is the author of Coding Literacy: How Computer Programming is Changing Writing (MIT Press, 2017) and the parent of three young children. She attributes much of what she knows about teaching college writing to her work as a Writing Tutor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison under former director Brad Hughes and with a dream team cohort of graduate student tutors. Find her on Twitter https://twitter.com/anetv or the web http://www.annettevee.com/.

Annette! This post feels a bit like the angel popping up over my right shoulder as I am deciding whether and how to add more student-to-student interaction in my composition course.

Could you talk a little more about how audio and video posts work in the context of a blog? Do students choose which tool to use in making a post or reply? Do you ask students to experiment with each modality at some point in the semester?

Ha, glad to be that little voice over your shoulder, since you’ve been an angel over my shoulder as well! Thanks for the great question.

In my Digital Humanity course (which is not a writing course), my co-teacher and I did require experimentation with different modalities for specific weeks. This requirement scaffolded them for the midterm and final, which required similar experimentation. We gave suggested platforms and resources for them to use, but did not require specific platforms. Often, then students introduced us to new platforms! A nice perk for us. 🙂 My experience is that audio and video posts get less student-student engagement, but it’s also been over a year since I implemented that. It might be different now if you used TikTok or FlipGrid–something more student-friendly than YouTube or SoundCloud, which was what we suggested.

[…] writing, such as discussion boards, Padlets, blogs (be sure to check out Professor Annette Vee’s recent post on Another Word about creating community through blogs) and […]

What a great idea! A first that was important to me from 2015 was being inducted into the Phi Theta Kappa Honor Society. This was a goal I set for myself when I started at Maria in May, 2014. As a non-traditional student in my 40s, this is my first time in higher education. I LOVE the experience of learning and meeting new people. On top of all of my other life responsibilities, it can be challenging sometimes to study and get my work done. So it was a very fulfilling experience to be able to do well and meet my personal goal!

Nice and very thoughtful article. While a student might not understand the importance of a blog, you have explained it so well that any person is bound to rethink her/his prespective.

Hi!

I completely agree. Very good post that highlights some important things about blogging.

Thanks for the informational blog which will surely be a big help for students.

I think to express thoughts on different spaces blog is a must for students.

Annette, you are so right, blogs do provide a sense of community among students. Also, what I noticed is that f you assign students to write about a certain topic but also leave them the choice of selecting the subtopic, this keeps their interested in the topic. also they do not realise that they are actually learning while doing research to write about that particular topic. Blogs are life saving!

That was a really thoughtful article, thank you for posting it. I really enjoyed reading, hope to hear more from you soon. Cheers!

Nice and very thoughtful article. While a student might not understand the importance of a blog, you have explained it so well that any person is bound to rethink her/his perspective.

Very well written article about importance of the blogs. Blogs can connect with each others. Cheers!