By Dr. Nancy Effinger Wilson and Samuel Garcia, M.A.

In “Stocking the Bodega,” Nancy discusses changes she made to the Texas State University Writing Center in order to create a panethnic, heteroglossic, communal, cosmopolitan, and transgressive third space writing center. On the writing center’s home page, for example, she added a link labeled “Englishes” that included definitions of various Englishes. Just as the writing center publicized the fact that this was an LGBTQ+ and veteran-friendly space, Nancy wanted to declare the writing center “language friendly.”

She also created a slideshow on the home page to showcase writers known for their bi-/multilingualism and bi-/multi-dialectalism: writers such as Gloria Anzaldúa, who code-switches between English and Spanish in Borderlands/La Frontera, and Geneva Smitherman, who writes in African American English. This slideshow replicated the experience of picking up these authors’ texts and experiencing the words for oneself. Since representation matters, an added benefit was that students of color could see successful writers/scholars of color who were proudly heteroglossic.

We need a national official policy of bi/multilingualism, not just for Blacks, but for all U.S. citizens. This policy would make mandatory, for all students going through school in the U.S., the study of ’foreign’ languages, and their respective cultures one of the subjects that students, regardless of race/ethnicity, could select,” and adds, ”Let me say this here, if you don’t never read or hear it no mo, nowhere else in life: I know of no one, not even the most radical-minded linguist or educator (not even The Kid herself!) who has ever argued that American youth, regardless of race/ethnicity, do not need to know the Language of Wider Communication in the U.S. (aka ‘Standard English’). (Smitherman 170)

We continue to ask our Latinx tutees and tutors for specific comments and recommendations as we continue this work. Below are our top goals and strategies.

Goal #1: Diversify the Writing Center’s Linguistic Ecology

“Hire tutors who can explain things in Spanish.” —Bianca, San Antonio, Texas

NCTE and CCC (College Composition and Communication) have recently generated a number of official statements focused on the issue of linguistic discrimination, including the 2021 “CCCC Statement on Ebonics,” the 2021 “CCCC Statement on White Language Supremacy,” and the 2020 “This Ain’t Another Statement! This is a DEMAND for Black Linguistic Justice!” In contrast, the IWCA’s “Position Statement on Racism, Anti-Immigration, and Linguistic Tolerance” has not been updated since 2010. The IWCA “Diversity Initiative” dates to November 20, 2006.

Perhaps linguistic diversity is not prioritized by IWCA because writing center administrators are not demanding it, and perhaps writing center administrators are not demanding it because they are beholden to university stakeholders who reify so-called Standard American English and assume that allowing for variations is a zero-sum game.

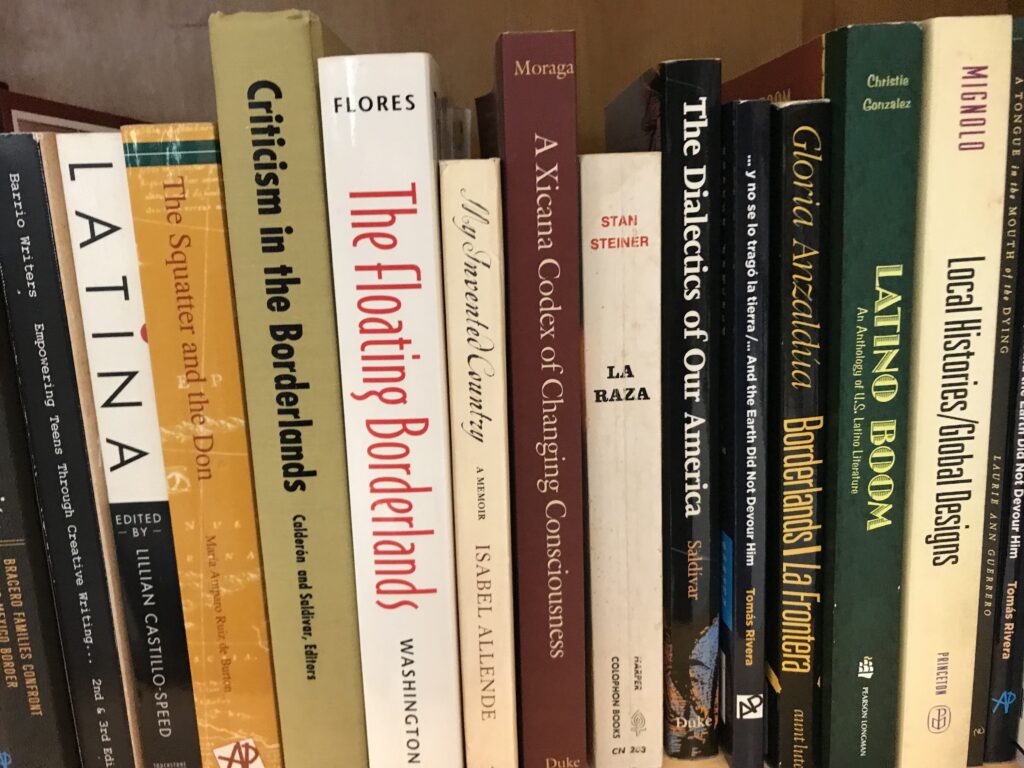

To counter this trend, our lending library contains books by authors who not only study African American English, code-switching/code-meshing, translingualism, and alternative discourses, but also use English varieties, Spanish, and Spanglish in their scholarly texts. The writing center thereby affirms that linguistic diversity and scholarship are not mutually exclusive.

This embrace of linguistic diversity extends to prioritizing the hiring of bilingual tutors and the encouragement of tutoring in the language the tutee prefers whenever possible. Indeed, in “Crafting a Composition Pedagogy with Latino Students in Mind,” E. Domínguez Barajas writes that “existing and emerging research on this demographic indicates that Latinos’ sociolinguistic profile is as impactful on their academic experience as is their socioeconomic and phenotypical profile” (216) and notes contemporary scholars’ efforts to “reconcile academic and vernacular discourses in order to minimize the social and linguistic alienation many Latino students experience in college” (218). Having successfully navigated academic discourse expectations, bilingual tutors can function as interlocutors, helping tutees recognize that the acquisition of the language of wider communication (LWC) need not come at the expense of one’s home language(s).

The participants in our focus groups clearly agree, as all of them recommended hiring bilingual tutors. Luisa noted the importance of having tutors who understand the difficulty of writing in English when one’s home language is Spanish: “Like the arrangement of the words changes from language to language, describing a subject with adjectives—which goes before?” And Denise specifically recommended hiring “a tutor who has Spanish as her first or second language and knows the difficulties of code-switching, so they can relate to the tutee.”

In addition to hiring bilingual workers, we encourage them to speak in languages other than English with one another if they feel comfortable doing so. When students walk into our centers and hear shared languages being spoken freely, this matters. Students have shared that sometimes the only reason they decided to make an appointment was because they knew they would be able to converse with someone who actually understood them and would be able to help them figure out how to phrase things that do not translate easily. In fact, Sam’s writing center has noticed an uptick of students seeking help from Spanish-speaking tutors. Students often note that they decide with whom to make appointments based on word of mouth. Obviously, writing centers need to recognize the presence of multilingual writers and need channels for communicating with these writers that there are the resources available to them.

All of this said, in the interest of full disclosure regarding potential pushback, a writing center coordinator told Nancy that “writing centers aren’t doing anyone any favors to allow students to use Spanish when they’re supposed to be learning English.” However, according to the 2023 “Bilingual Education and America’s Future: Evidence and Pathways. A Civil Rights Agenda for the Next Quarter Century,” “the benefits of bilingual education and bilingualism go beyond academic and English language outcomes, with benefits for students’ home language development, cognitive functioning, social-emotional and sociocultural outcomes, and students’ future employment and earnings.” Clearly, then, the disservice would be to ban the use of languages other than English in the writing center, especially given that the world outside of college is not monolingual.

Goal #2: Diversify Your Space(s)

“It was quite a shock to see so many White people in one place.” —Jesus, Harlingen, Texas

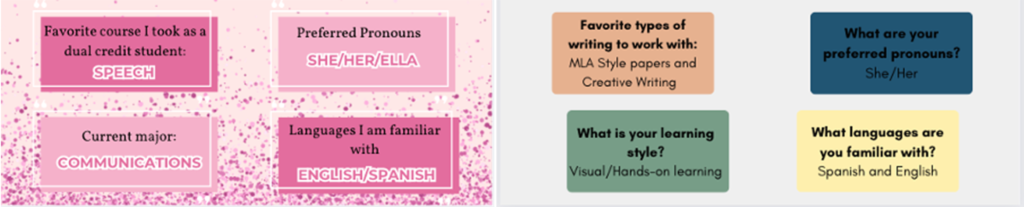

Not only should writing centers hire bi- and multilingual tutors, they should publicize this fact on their websites. For example, in addition to badges that indicate, say, a tutor’s Allies training and Veteran status, we recommend identifying those who know more than one language in order to increase multilingual visibility for students who may not know the option even exists.

Sam’s center has tutor bios posted online and by the front desk that includes information about tutor interests, specialties, and languages they are familiar with.

Online and in the center, we also showcase photos, pictures, artwork, and art displays designed by the students themselves (like rotating art or boards). It helps get rid of that sterile feeling that university offices can sometimes have and celebrates our Latinx students’ cultures. For example, we are currently displaying artwork by Alejandra Gonzalez Zertuche, a former Texas State University student.

We continue decentering Anglo culture in the center through some of the smaller choices that we make. For example, in addition to Hershey’s kisses in our candy jar, we included candy that one would find in Latinx communities (Glorias, Tix-Tix Fizz, anything with Chamoy) and offer Mexican hot chocolate alongside coffee. Finally, we decorate for a variety of holidays, including, at this time of year, Día de los Muertos.

Goal #3: Tap the Power of Ganas

“It’s just really good to have someone who is honest and doesn’t baby you.” —Luisa, El Paso, Texas

Unfortunately, deficit assumptions surface in the writing center, as when the coordinator commented that “writing centers aren’t doing anyone any favors to allow students to use Spanish when they’re supposed to be learning English.” Rubén Garza notes, “once students step into the context of the classroom, educators may perceive [the students’] unique assets as problems, complex challenges, or differences that are misinterpreted. As a result, educators often label students as unmotivated, withdrawn, or academically incapable” (297). Individuals such as this coordinator failed to acknowledge the accomplishment that being able to communicate in two languages represents. By reifying English, however, he was belittling Spanish and Spanish speakers.

In contrast, Nate Easley, Jr., Margarita Bianco, and Nancy Leech analyzed autobiographies of 103 immigrant and first-generation Mexican heritage students and followed up with interviews and focus groups; they found that “ganas, a deeply held desire to achieve academically fueled by parental struggle and sacrifice,” was “evident in 46% of the autobiographies and 48% of the interviews” (169). Easley, Bianco, and Leech advocate teachers using this finding “to challenge the deficit assumptions about the students they teach and the families who raise them” (176). Rather than operating from a deficit model and cautioning students that “we are not a fix-it shop,” which is insulting to the majority of students who engage in the labor to develop their writing skills, writing centers should clarify that we understand that students are busy and will come to the appointment ready to work, as will our tutors.

We tap into ganas when we provide a space for students not only to challenge standard language practices but also to communicate effectively in the language of their choice. Although tutors should be friendly and use their sessions to help tutees craft messages using the languages they desire, if a tutee asks if a word in Spanish means what they think it means, we should answer. Luisa’s comment above reminds us that spending too much time affirming a writer may be unnecessary.

Goal #4: Foster Comunidad

“It’s just so cool that all the tutors seem like they actually care.” —Samantha, San Antonio, Texas

When we think of comunidad, we think of the need to serve and promote a sense of belonging in some way. We emphasize during training that it is our duty to help our students feel like a member of the university community, and we make it a point to hire students who reflect our student body. But there is more that goes into comunidad than just that. In “The Languages in Which We Converse,” Muhammad Khurram Saleem explains that this type of relationship building is a form of emotional labor “that let[s] us know we are loved, cared for, welcome, and valued.”

Foster comunidad by staffing the center with tutors that students can identify with. When hearing tutors speak languages other than English in the center, multilingual students feel understood and supported, and they feel a greater sense of belonging within the university because it is apparent that at least one part of the institution cares.

Conclusion

According to Ramirez, Puente, and Contreras, “despite their increasing enrollment rates, Chicana/Latina college students continue to experience racial/ethnic and gendered isolation, academic and culture shock, feelings of imposter syndrome, and a lack of belonging at the university” (619). The first three goals outlined in this article—diversifying our linguistic ecologies, diversifying our spaces, and recognizing that our tutees are academically driven and capable—address these specific problems. And with those goals met, comunidad should follow.

Although, this is not necessarily true—as tutees will see through diversification initiatives that are performed for them but not with them. Nancy made this misstep when she wrote in “Stocking the Bodega” that “tutees can learn ‘standard’ and global Englishes and other languages, traditional and alternative rhetorics, and a variety of literacies” (4). She should have added that writing center tutors and administrators must also diversify their own linguistic and rhetorical skills if the goal is a truly heteroglossic, communal, cosmopolitan, and transgressive third space bodega writing center. Ironically, when this across-the-board embrace of linguistic and rhetorical diversity occurs, the goals we are advocating will organically occur, comunidad included.

Works Cited

Barajas, E. Domínguez. “Crafting a Composition Pedagogy with Latino Students in Mind.” Composition Studies, vol. 45, no. 2, Oct. 2017, pp. 216–18.

Easley, Nate, Jr., Margarita Bianco, and Nancy Leech. “Ganas: A Qualitative Study Examining Mexican Heritage Students’ Motivation to Succeed in Higher Education.” Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, vol. 11, no. 2, Apr. 2012, pp. 164–178.

Garza, Rubén. “Latino and White High School Students’ Perceptions of Caring Behaviors: Are We Culturally Responsive to Our Students?” Urban Education, vol. 44, no. 3, May 2009, pp. 297–321.

Porter, Lorna, et al. “Bilingual Education and America’s Future: Evidence and Pathways. Executive Summary.” Civil Rights Project – Proyecto Derechos Civiles, Civil Rights Project – Proyecto Derechos Civiles, 1 Jan. 2023.

Ramirez, Brianna R., Mayra Puente, and Frances Contreras. “Navigating the University as Nepantleras: The College Transition Experiences of Chicana/Latina Undergraduate Students.” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, vol. 16, no. 5, 2023, pp. 619–31.

Saleem, Muhammad Khurram. “The Languages in Which We Converse: Emotional Labor in the Writing Center and Our Everyday Lives,” The Peer Review, vol. 2, no. 1, 2018.

Smitherman, Geneva. Word from the Mother: Language and African Americans. Routledge, 2006.

Trimbur, John. “Multiliteracies, Social Futures, and Writing Centers,” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 20, no. 2, 2000, pp. 29–31.

Wilson, Nancy Effinger. “Stocking the Bodega: Towards a New Writing Center Paradigm.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 10, no. 10, 2012, pp. 1–8.

Nancy Effinger Wilson is an Associate Professor of English. She is Director of Lower-Division Studies in English at Texas State University, having previously served as the university’s Writing Center Director. Nancy’s publications include “Bias in the Writing Center: Tutor Perceptions of African American Language,” published in Writing Centers and the New Racism (edited by Laura Greenfield and Karen Rowan); “Writing Center Tutor Corps: Creating a Veterans-Tutoring-Veterans Program,” co-written with Micah Wright and published in Writing Lab Newsletter: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship; and “Making Space for Diversity,” published in College Composition and Communication.

Samuel Garcia is a lecturer of English and Assistant Director of the Writing, Language, and Digital Composing Center at Texas A&M University – San Antonio. He received his M.A. in Rhetoric and Composition from Texas State University in San Marcos, Texas. Sam’s scholarship explores intersectionality and liminality within writing centers and composition pedagogy, as well as the practices writing programs can use to help make place for Chicanx, first-gen students within higher education.