By Rachel Herzl-Betz and britty cox, Nevada State University

Once, my (Rachel’s) direct supervisor in the Provost’s Office asked whether we had ever presented on our writing center leadership structure. At the time, I laughed it off. Why would we talk about how we keep the trains running on time? As we (Rachel and britty) thought more, that idea connected to larger questions about writing center interdependence and the ways that we all get used to what we do. Like a grad student learning to teach, we often watch our mentors, emulate their choices, and forget that structures have a tangible impact on what we can and cannot accomplish. We know that much of what we do, in praxis and pedagogy, is only possible because of how we organize our labor.

In Nevada State University’s writing center, our group of undergraduate Writing Specialists and Fellows divides themselves into five teams which control almost every job in the center. Every task, from major events to minor decorating decisions, is shaped by the team members who choose to take it on. However, as we began planning for this post, we weren’t sure whether our experience could be generalized. Could other centers draw on what we’ve done, or is it an example of how local context defines the possible? Together, we want to use this blog space to explore two interconnected questions:

- How can centers foster professional development and collective ownership, without exploiting their teams?

- What can interdependence look like in writing center daily practice?

Where We Are

Nevada State was established in 1999 to serve a diverse population of local students. Today, roughly 75% identify with a historically marginalized race or ethnicity, only 23% identify as continuing-generation college students, and almost the entire student body originates in the Las Vegas area. As of Spring 2024, Nevada State University is a mostly-commuter campus that serves just under 7,000 students.

Our Writing Center aims to celebrate collective leadership, transparency, and co-creation of the space. We’ve worked to draw on a disability-centric understanding of interdependence which shifts us “away from the myth of independence, and towards relationships where we are all valued and have things to offer” (as stated in this blog by Mia Mingus). In interdependent spaces, disability and neurodivergence aren’t problems to be overcome, but rather sites of wisdom to be incorporated into communal knowledge. We both identify as neurodivergent, as do many of our student colleagues, so it makes sense that we would aim for a kind of access intimacy in our working lives. One might imagine that would be simple in such a collaborative profession, but writing centers have a long history of celebrating independence as a goal, both for visiting writers and for our employees (a concept that is explored in this article by J. M. Dembsey). Building another kind of working structure must be intentional, even in the most supportive working spaces.

As writing center leaders, we also know that tutor training transfers to a wide range of contexts. Scholars have established that the skills, research, and collaborative know-how that writing centers require supports tutors’ future goals. And, in fact, we often frame the jobs we offer as more than mere labor, because we offer a shared mission and extensive opportunities for employees to develop their skills. However, it can be difficult to offer growth opportunities without asking too much of our student colleagues. Even the most valuable professionalization can inflict harm when it’s offered without attention to power and marginalization (emphasized in this chapter by Yanar Hashlamon). Centers may offer jobs with supportive colleagues and exciting learning opportunities, but they remain jobs, and ones that often do not pay a living wage. As leaders, we must remember that we have control over our teams’ employment and, sometimes, their grades. When we ask our employees to take on a heavy load, it’s rarely easy for them to say no.

So where does this leave a writing center leader who does not want to overwork their team? We do not want to infantilize our employees; they are adults who deserve to be treated like colleagues. Plus, drawing on the collective team can be the only thing keeping a director or coordinator from burning out on the job (as discussed in this book). In theory, we must give all of our team members real agency without embracing a structure that “exploits undergraduate labor in the name of student success”. But what does that look like in practice?

Establishing a Collective Norm

Dr. Kathryn Tucker created the center in 2014 as a 6-person offshoot of the Student Academic Center. Now, it employs 15-18 undergraduate Writing Specialists and Fellows who lead sessions, workshops, course-embedded tutoring, and research in writing studies. Our team structure originated in 2017, just three years after the center was founded. By then the Specialist team had grown to twice its original size and the structures that had worked for 6 student workers had grown unwieldy. Dr. Tucker had successfully convinced the campus to hire a new Assistant Director, but that still left them with more than a year without additional support. The center had a terrific Coordinator, Paige Hall, but there was also a ton of work to get done. Inspired, in part, by a conversation at an IWCA conference, Dr. Tucker invited the team to break themselves into a small set of teams. They would meet semi-regularly during CWCE (continuing writing center education) training to plan new projects, gather feedback on ideas, and ensure that the most experienced tutors weren’t taking on more tasks than they could handle.

Before the teams existed, student workers already had the option of leading any task in the center and were encouraged to play a major role in new policies. As such, the new structure was largely welcomed because autonomy was already the norm. The difference was the structure and distribution, rather than the expected engagement. The teams only helped student workers focus their energies on a specific list of tasks with a built-in subset of collaborators. That way, everyone could find a way to help, and the more experienced tutors had a built-in group to mentor. In a moment when the earliest employees had begun to graduate, it also helped ensure that institutional memory wouldn’t graduate with them. Now, the teams act as a model for our center structure and help new hires find their place. We’ll address this more below, but flexible structures can be overwhelming for new hires. Breaking the work down into specific subcategories can provide built-in mentors, and make navigating the new space feel more manageable

Teams in Action

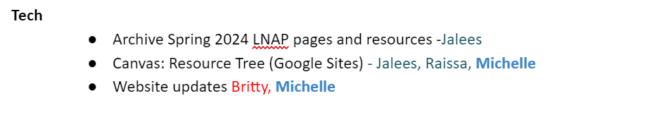

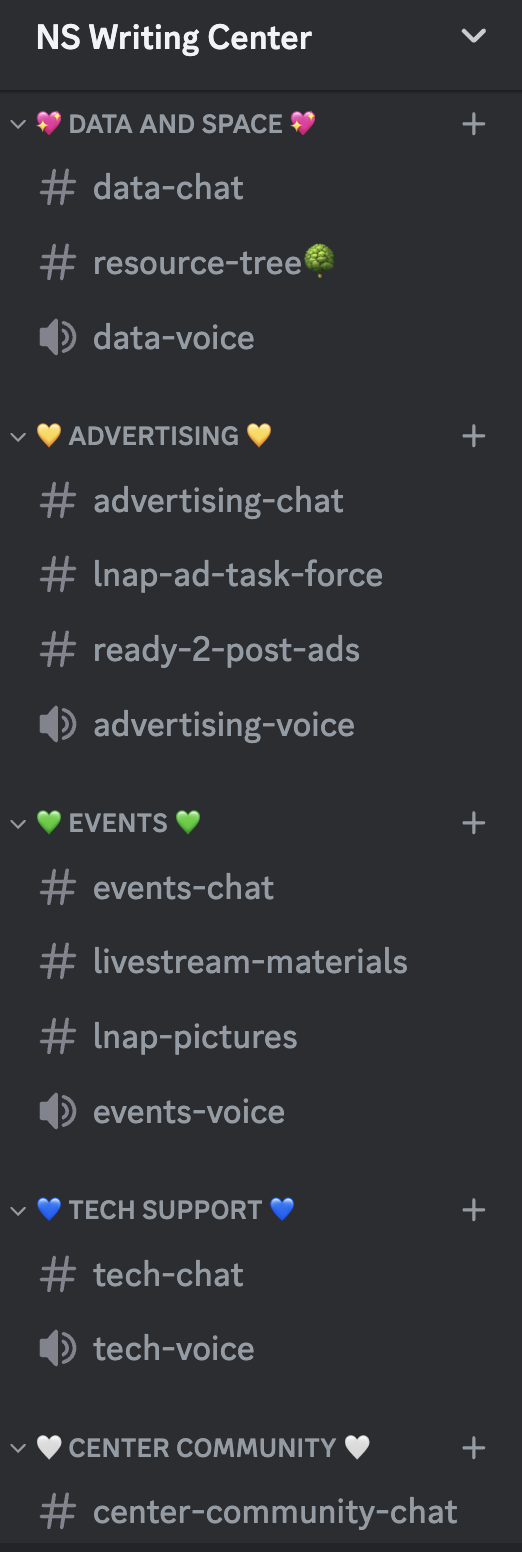

Most projects in the center are run by one of five teams: Events, Advertising, Data and Space, Technology, and Community. Events oversees the management and planning of the events we host on campus. Advertising makes materials on how we present ourselves to the campus community, services we offer, how to visit us, etc. Data and Space handles the archiving of data from sessions as well as thinking about how our space looks and functions, both in person and online. The Tech team assists with all things technology, from computer software updates to our website design. And finally, the Community focuses on how we connect to each other as a team.

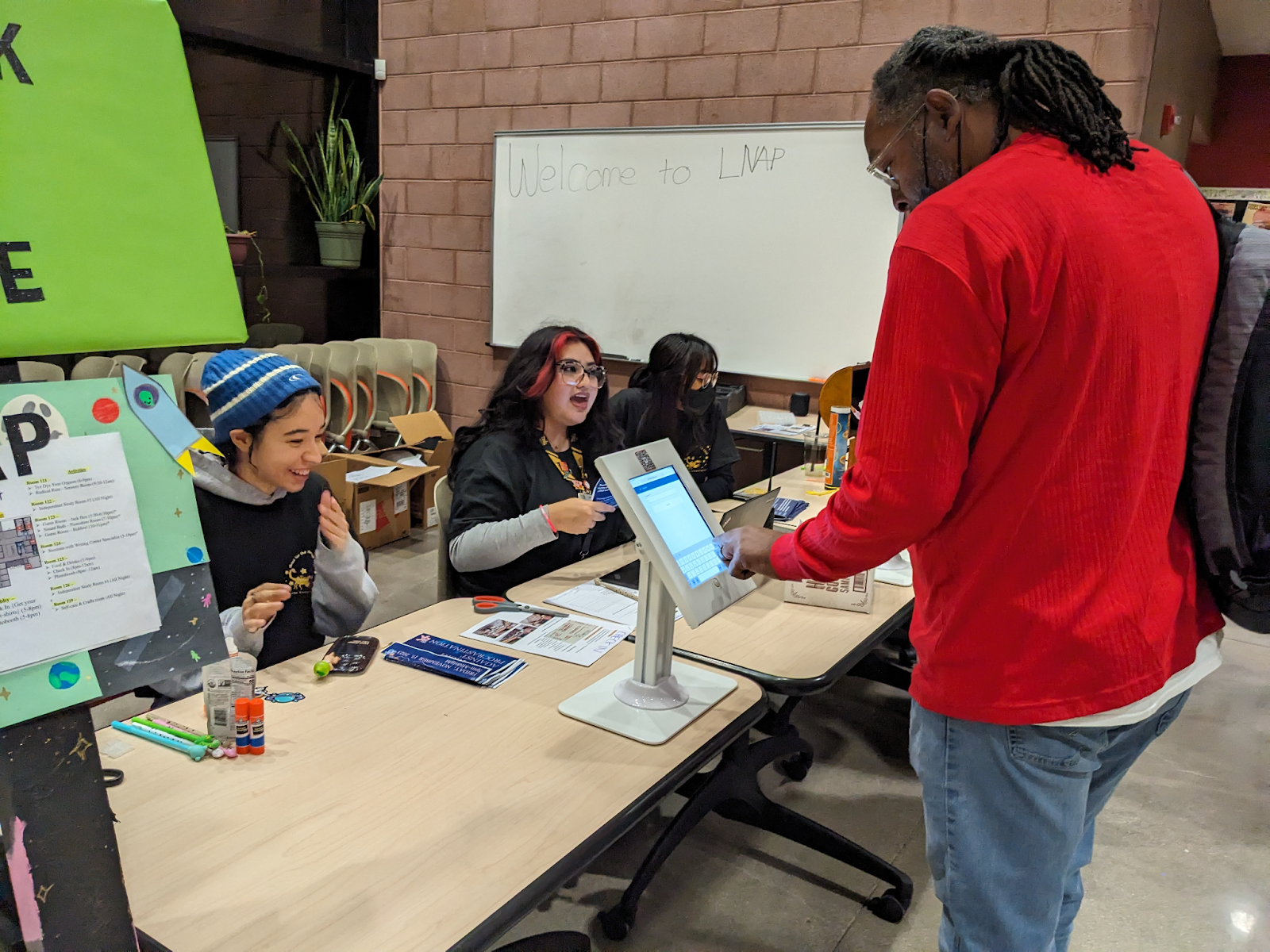

We meet regularly with each team as they work on projects, such as the Long Night Against Procrastination (LNAP) or redesigning the Writing Center website, but we primarily provide training and guidance so they can do the work themselves. This student autonomy has led to some of the most successful innovations in the last few years, including a redesign of the center space, most of our hybrid structures for LNAP, and our use of discord for remote communication. When it comes to meeting our students where they are, the student workers will always know more than we do, so we do our best to follow their lead.

Teams are chosen at the beginning of each semester, which allows tutors to try new teams or stay with those they know. Allowing them to pick their teams gives space to explore areas of our center they’re uniquely interested in whether this be because they have skills already or would like to learn something new. People who have been trained for at least one semester are welcome to choose more than one team. This means, for example, sometimes we have someone who is on Events but also on Advertising. This can be particularly helpful for people wanting to apply skills in different areas of the center. While the different teams focus on specific areas of our space, there is often a lot of overlap and collaboration that happens between teams. Events may work with Advertising and Tech for event related tasks to ensure the outreach and tech support for an event is covered. It is interesting to see how these subsections of the teams help the center operate as a whole. Each team and their members play an integral part.

Every week teams can pick or add tasks to the weekly project list. They get to pick what they’re doing and often how to do it. There is no “quota” for how much must be done in a given week. These are simply tasks and projects that can be done when there isn’t a writing session. Some people are comfortable taking more on than others, and that autonomy has always been central to the system.

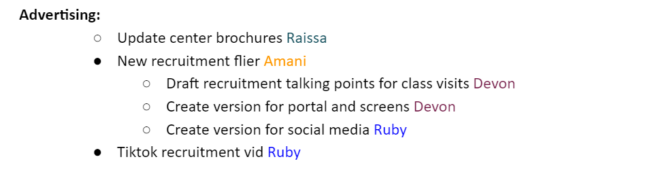

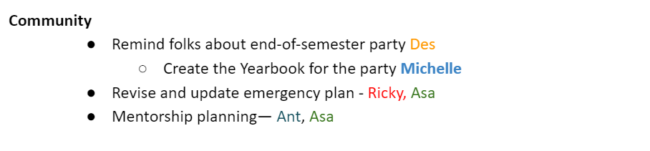

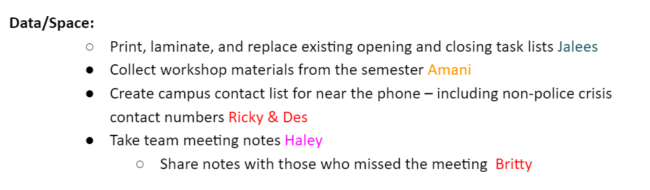

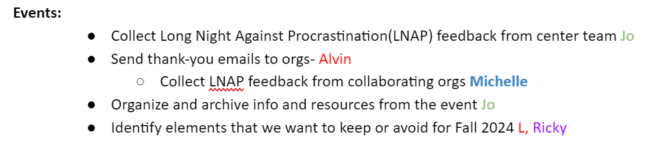

Below, these images offer a sense of what our weekly project lists look like. Anyone on the team can add, sign up for, and collaborate on any item.

Possibilities, Challenges, and Implications

Our structure aims to foster interdependence and a sense of collective ownership over our space. Ideally, most projects include multiple collaborators, so that team members have support in new genres and so we can all swap out when our bodyminds need a break. This structure also allows our center to provide a wider range of services. Writing centers are always pursuing a dozen tasks beyond one-on-one writing support, and most of those tasks are only possible if several people can step into similar roles. This is particularly true at smaller centers, like our own, where we only have two employees who aren’t undergraduate students. In this leadership model, most tasks are owned by the team (rather than by a single individual), and multiple people are empowered to take the lead on a new idea. I (britty) remember having a conversation at 4C’s collaborative in Chicago where people were surprised by the autonomy we get in the space. I told them that structure is widely why I thought I could be the coordinator because the tools were already given to me to succeed and be confident in what I do. I know I can lead the space because I was already a leader in that space as a student worker. As a late diagnosed AuDHD person who has always struggled with finding a place I felt like I belonged in, this structure and format let me thrive because it met me where I was and it was easy to accommodate for my disabilities. That is the benefit of interdependence and collective ownership.

With that distributed power can come logistical challenges. Even though the center’s tasks may be distributed, the structure still requires communication, mentorship, and delegation. Even the most enthusiastic new employee may not have experience troubleshooting a new workshop or preparing for an all-campus event. Mentors need to be checking in at regular intervals and during challenging tasks. Often our office will be the first place an employee has been given this kind of freedom on the job, so we provide extra structure for those who want to know they are going in the right direction. Our forms of mentorship have to be as flexible and adaptable as the structure itself.

Within this structure, employees rarely refuse to contribute. However, some employees do have a hard time seeing themselves as integral parts of that larger whole. For example, some student workers need us to assign their tasks for weeks (or months) before they feel comfortable claiming anything on their own. The real shift happens when they internalize the idea that we aren’t giving them busy work. We genuinely need them, and that includes their current abilities, disabilities, and forms of neurodivergence. Moreover, if they have to step back because they are overstimulated or having a flair up, we will all be there to help carry the weight. These folks are already hard-working and most have had other job experience; they just need to get used to feeling a sense of responsibility to the center community (and to others having a sense of responsibility for them). It’s a philosophical shift, and one that suffuses our entire center– from recruitment and hiring through training and support.

Perhaps the most important potential downside of this model is the weight it can place on low-paid tutors. We mentioned above that students rarely opt out of collaboration, but they often do try to take on responsibilities that are literally above their pay grade. As much as those of us that run centers do not want to replicate academia’s worst traits, it can be easy to reward competence with more labor, to encourage overwork, and to miss when employees are taking on more than they can handle. All work-related labor must be done while on the clock, but since our workers are capped at 19.5 hours a week it can be hard for them to manage that time. For example, someone may take on 3-4 tasks in a given week without fully realizing the time needed for each task. Even when I (britty) was a student worker, I sometimes found myself working off the clock to get a deadline done. It often didn’t bother me because I was passionate about it and found enjoyment in the work, but that’s still unpaid labor. This is why as leaders in the space, we (Rachel and britty) must pay extra attention to ensure our workers aren’t being overworked. As neurodivergent leaders, we also have to model how students can make their jobs meaningful without making them into their entire lives.

We’ve also found that we, as employers, can help folks resist overwork by setting appropriate expectations with our colleagues elsewhere on campus. Writing centers should be pedagogical spaces, which means that students need the opportunity to do these tasks imperfectly. If a flier is being co-created by two sophomores who are learning the genre, it likely will not look like it was created by a professional with 10 years of experience. Leaders need to be ready to frame these moments as valuable learning opportunities and moments for the center to think outside of the box – both for themselves and for campus stakeholders.

Our experience suggests that building collaboration, trust, and interdependence in a center may also require giving up a measure of our autonomy as leaders. If we want a group that’s comfortable coming up with their own advertising campaigns and workshops, we also have to be ok with Tiktok jokes we don’t understand, a workshop draft that goes through five rounds of revision, and a team member who needs to tag out for a mental health day. The work our team members are doing must be both essential for the center and (at least in part) out of our control. As leaders, we can offer mentorship, but we cannot simply take over if the result isn’t what we expected. I (Rachel) have been surprised with redesigns of everything from the book check-out system to our t-shirt orders and the changes were almost never what I would have done myself. They were better. Moreover, they often came from students who’d originally needed convincing to see themselves as necessary members of the center team.

In many ways, we hope our model resembles a writing center session. We could take over the task, but what voices, innovation, and learning opportunities do we lose when we don’t let our students do the work themselves?

Rachel Herzl-Betz (she/her) Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor of Humanities and The Writing Center Director at Nevada State University. Her research focuses on intersections between writing studies and disability justice. Recent publications include “A Space for Small Inventions: Access Negotiation Moments and Planned Adaptation in the Writing Classroom” (2022) in Composition Forum and “Perdiendo mi persona: Negotiating language and Identity at the Conference Door” (2022) in Pedagogy: Special Issue on Undergraduate Research.

britty cox (they/them) is the Writing Center Coordinator at Nevada State University. Before becoming coordinator, they worked in the same center as a student worker Writing Center Specialist. Their areas of interest for research are related to Fat liberation, Queerness, Autistic communication and writing studies.