By Saurabh Anand, University of Georgia

As an international graduate student who speaks five languages and writes in three, I have survived multiple instances of North American writing epistemology hegemony across academic and professional situations. When they happened, such experiences surprised and frustrated me because India, my home country, is one of the world’s largest English-speaking nations in a multilingual context (Kachru et al. 99). The incidents above had (involuntarily) forced me to sacrifice how I view myself as a multilingual writer, where “communication always involves a negotiation of mobile codes” (Canagarajah 8). Those live events, rather traumas, came and went, but they stayed with me for a while. I interpret those occurrences as acts of depriving me of my translingual being, where I had to give my forced consent to “single language/single ‘norm’ of a single, uniform (‘standard’) language” (Horner and Selfe 5) to be within American academia. Sadly, I am not alone with such experiences. In my article on my multilingual writing center labor, I shared my interactions with other writers around this theme.

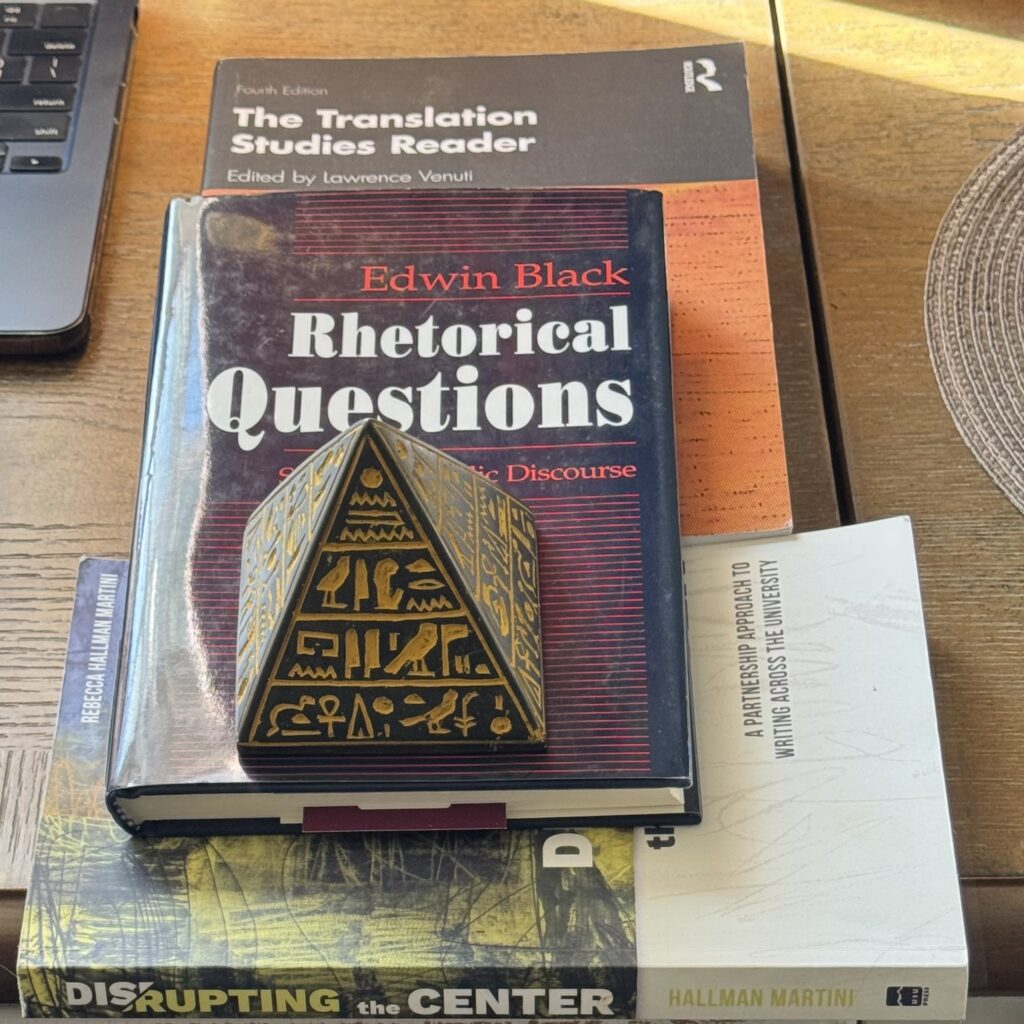

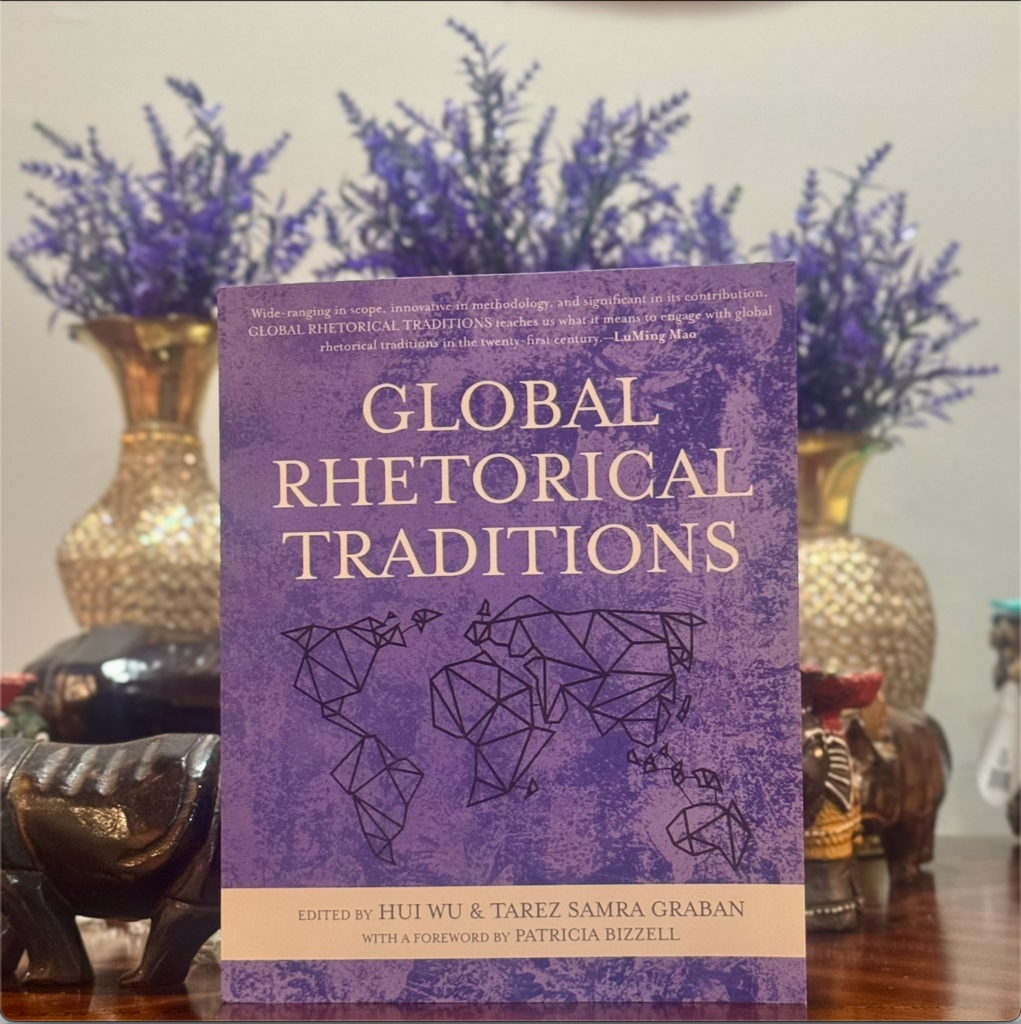

As the assistant director of a writing center, I aspire to ensure that multilingual Anglophone writers and all writers do not face the challenges I previously mentioned. So, in my early-career writing program administrator position, I often focus on supporting multilingual writers (like me) who use writing centers by continuously developing and brainstorming dedicated resources useful for writers and their tutors. Hence, via this piece, I propose that my writing center colleagues include Global Rhetorical Traditions (GRT, Wu & Graban) as a professional development but, more importantly, a rhetorical resource reading that could shed light on non-western, hence anti-racist, multilingual, and multiple literacies valuable to writing center pedagogy (Trimbur 89; Wang-Hiles 32). By “rhetorical writing center resources,” I mean those that recognize international writers’ (often multilingual) social contexts and honor their language identities.

As you read this piece, please know that it is my choice to frame it as a book review embedded in storytelling. Storytelling, for me, is not just about retelling past events; it provides a nuanced ability for the teller to thread their detailed experiences into their lived narrative and provide their readers an opportunity to connect with the teller on a deeper meaning-making level.

As a multilingual writing center tutor and administrator, I found reading this book to be nothing less than how a child feels returning to their homeland, where languages, logic(s), and literacies are multitudinous, interconnected, and interdependent. In their edited collection on Global Rhetorical Traditions (GRT), Drs. Hui Wu and Tarez Samra Graban assert that globally, persuasion strategies, discussions, and conversational norms often stem from (sub-)cultural-specific conventions (linguistic and non-linguistic modes) and are often soaked in plurilingualism—the ability to work and navigate situations across multiple languages. GRT opens the door to the theory-driven journeys of people achieving communication success through all literacy repertoires while they engage in multiplex negotiations within them. In my own tutoring, I often attempt translation theories and practices informed by them—something many multilingual writers and I deeply resonate on a daily basis in our academic and personal lives as immigrants or coming from such family backgrounds.

Reading GRT strengthened my tutoring beliefs and values shaped by my upbringing in an Anglophone country. In such a context, languaging across languages leads to setting a foot into penetrating cultures and evolving one’s logic as second nature based on the situation. Such philosophies are often countered by native-English superiority ideologies and/or assimilating multilingual writers to conventions of multilingualism in Western societies, including educational spaces, something this book banishes in its tangible existence by centering multilingual experiences.

GRT offers a clear view of the complexities of Global Anglophone rhetorics, which are often shaped by traditional Euro-American perspectives, including institutional spaces. Hence, I see this book as a sustainable educational resource that is immensely valuable for non-writing-center studies specialists, who are often writing-center personnel and would easily understand its straightforward approach with multiple historical evidence of how communication worked and mushroomed across societies. In most instances, these are usually monolingual writing tutors genuinely interested in boosting their writers’ confidence in writing but do not usually know about their writers’ educational and linguistic contexts. The examples in the GRT book can help tutors better grasp their writers’ perspectives.

As a multilingual tutor, I’ve realized the value of reading resources like GRT to enhance my professional skills and understanding of multilingualism’s historical context across cultures. This book challenges common misconceptions about multilingual writers and highlights their diverse needs, which is significant given their large presence in U.S. college writing. As a graduate student and writing center staff member, I found that reading this book has boosted my confidence in tutoring and WPA identity by motivating me to dive into more variations of multilingual writings and their assessments to think about how I might design professional development workshops for my colleagues. GRT offers insights into the experiences of transnational societies, enabling tutors like me to provide more comprehensive support for student writers and the people they interact with while focusing on specific cultural nuances.

As a book, GRT provides a variety of societal and cultural nuances beyond Euro-American geographies. It explains with concrete examples why and how definitions of rhetoric in each “rhetorical historiography” (p. xvi) as GRT’s foreword writer and renowned rhetorician Dr. Patricia Bizzell says. She advocates others to indulge in comparative and global cultural rhetorics are important with their significant methodological themes complicating indigeneity and borderlands. Many of those nuances we encounter in our writing center too, through our writers.

As such, GRT provides WPAs with more international administrative visions and tutors with specific, situational, and closer-to-home intellectual support for better understanding and more positive tutoring outcomes. As both of them above, the book reminded me to be sensitive to multilingual writers and their distinctive language repertoires while tutoring them in the writing center I currently or will work in the future. I was able to reconfirm many of my past multilingual tutoring instances where I realized I was a bit short of guidance on tutoring multilingual writers than usual. In short, GRT provides tutors with specific, situational, and closer-to-home intellectual support for better understanding and more positive tutoring outcomes.

This is especially urgent when ongoing decolonial/postcolonial studies inform discussions within writing center scholarship, and such pedagogical tactics begin to mushroom at the center, and US Federal Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) education initiatives are in danger. In this way, GRT could also be an equal contributor that uses English as a language as a (decolonial) sword to center global Anglophone language dissemination, keeping multiplicity at its one core ethos. Writing centers could use this pedagogy as a symbiotic resource to advance sustainable writing conventions, practices, initiatives, and awareness. As a writing center administrator, I often see multilingual writers bring such literacies to the US writing centers. Such practical pedagogical language and rhetorical notions can be further amplified, but these are not acknowledged enough in writing center scholarship as multilingual writing and tutor labor, too.

As someone with a background in applied linguistics, I see this book as an important and intellectually stimulating resource for writing center tutor preparatory courses that expand the generic expectations of college writers in the US. For example, in an activity for a course that I teach, I often ask my mentees, pre-service or newly hired tutors, to close their eyes and imagine their potential tutors. Most of the time, they imagine a white monolingual person. Though this type is true for my university, it is also not the only truth. However, is this their fault?

No, the real cause of such stereotypes is the institutional ignorance of diverse writers who stay invisible in the academy. The resources such as GRT acknowledge them. First, recognizing such diverse writers and their lives/literacies exist. Second, GRT reveals the vital need for identity-based support, which is essential for triggering globalization, diversity, equity, and inclusivity-induced ethos within university writing support programs.

For example, many chapters in the book provide writing center tutors with practical insights into how languages, logic, and societal logic sets evolve in a community or a community from a specific geography, and such sets of logic are, at times, multifocal and multilayered. One could easily point this out by reading GRT’s chapters on East African, Indian, and Nepali rhetorical contexts, given how plurilingual these societies are. As a writing center tutor, while consulting with Hindi speakers, I have witnessed my writers translating my guidance while taking notes in the form of text from Hindi to English or even code-meshing grammar (Hinglish) and other linguistic elements. As a writing center studies practitioner/researcher, I believe that such professional moments could provide tutors with conscious and active knowledge about multilingual minds and their ways of being due to various cultural, social, and political historical influences.

Given the comprehensive coverage of non-Euro-American rhetorical conventions and histories depicting foundations of literacies across non-Western frames, I also find the book’s cost reasonable. GRT is a worthy investment for a writing center theory and practice course for pre-service or early career tutors that often involves students from various disciplines, and the scope of this book can easily be extended to the student’s long-term professional and academic goals. Referring to GRT, tutors can learn, at times, how one’s writing, and other educational goals coming for a writing center consultation could also be impacted by the complexities of geopolitics and their cultural backgrounds. In fact, writers who come from the same region may have different factors impacting them due to socio-political, contemporary, and Indigenous background differences, leading one to scarcity or dominance. One example of this is GRT’s chapter on Polynesian rhetoric.

As a multilingual individual, I appreciate the editors’ intellectual care in recognizing translations as a translingual ethos essential for global communication efforts. They also alert us as educators to the fact that global communication processes often require intercultural competence, a blend of languages, and the intersection of various social institutions and alliances, such as religion and politics. The chapters in GRT focusing on Arabic, Islamic, Mediterranean, and Indonesian rhetorics further elaborate on these concepts. An extensive exploration of the rhetorical contributions of Russian, Irish, Chinese, and Turkish world contributors could illuminate the writing center tutors the historical influences that specific international or diasporic writers from particular peripheries carry forward in their work. Reading GRT could encourage preservice or early-career tutors to think beyond standard monolingual conventions (primarily English) and reconsider tutoring principles and beliefs. Talking about principles and beliefs, this book also highlights the necessity of moving beyond Christian religious perspectives. Such topical chapters could help WPAs and tutors address how these faith traditions could complicate tutoring. This discussion has been recognized as an important area for writing center research already, as noted in Out in the Center: Public Controversies and Private Struggles (Denny et al.).

The GRT is a comprehensive and influential collection of commentaries that powerfully asserts that rhetoric encompasses much more than traditional Greek and Roman concepts, as illustrated on every page. At the same time, this book challenges educators and tutors in the writing field to consider why we have not endeavored to understand the presence and significance of rhetoric beyond our familiar surroundings and how it has been treated in academic discussions in Western academia. I view this book as a groundbreaking and necessary exploration of alternative histories of rhetoric. I often observe that the translations of these rhetorics impact one’s writing ideologies and thoughts within U.S. writing centers, particularly when supporting multilingual writers. Understanding the struggles of anglophone writers, who are often multilingual, in negotiating between languages is crucial.

Incorporating GRT as a resource into the Writing Center tutor preparatory courses could be beneficial in several ways. First, the non-Western historical insights can serve as valuable resources for Writing Center staff to better imagine and enhance support for multilingual writers. Second, examining society-specific examples, especially from anglophone countries, will help writing center personnel devise strategies to challenge beliefs in native-English superiority within U.S. educational contexts, informed by their institutional characteristics and other factors. Given that writing programs have a long-standing tradition of collaboration with allied disciplines to adapt and reimagine their offerings, engaging with GRT will enable Writing Centers and non-Western rhetorical traditions to brainstorm ways to foster support for diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds, thereby promoting multilingualism and translingualism.

Works Cited

Canagarajah, A. Suresh, editor. Literacy as Translingual Practice: Between Communities and Classrooms. Routledge, 2013.

Denny, Harry, Robert Mundy, Liliana M. Naydan, Richard Sévère, and Anna Sicari, editors. Out in the Center: Public Controversies and Private Struggles. Utah State UP, 2018.

Horner, Bruce, and Cindy Selfe. “Translinguality/Transmodality Relations: Snapshots from a Dialogue.” 2013, University of Louisville, Unpublished working paper.

Kachru, Braj B., Yamuna Kachru, and Cecil L. Nelson, editors. The Handbook of World Englishes. Vol. 48. John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

Trimbur, John. “Multiliteracies, Social Futures, and Writing Centers.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 30, no. 1, 2010, pp. 88–91. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43442333

Wang-Hiles, Lan. “Empowering Multilingual Writers: Challenging the English-Only Tutoring Ideology at University Writing Centers.” NYS TESOL Journal, vol. 7, no. 2, 2020, pp. 26–34. https://orig.journal.nystesol.org/july2020/03_BR1.pdf

From Delhi, Saurabh Anand is an assistant director of the Willis Center for Writing and a multilingual doctoral student in the English department at the University of Georgia. He is a recipient of NCTE’s 2024 LGBTQIA+ Advocacy & Leadership Award and IWCA’s 2023 Future Leader Award.