By Kerri Rinaldi, Immaculata University

Over the past few semesters, the tutors at the writing center I direct have expressed a desire and a need for more training on supporting multilingual writers. I heard their requests, but at first, I wasn’t sure how much additional training time to devote to this topic. After all, our small campus (2,500 students) has an even smaller population of international students and multilingual writers (just 1-5% of all students). And, my tutors do take a tutor training course that includes readings and instruction on multilingual writers.

Still, I decided to dig in a little deeper into their request. Although international and multilingual students make up a relatively small portion of the university’s total student body, these writers are disproportionately represented in the population of students who use the Immaculata University Writing Center (IUWC) (27%). IUWC tutors receive training on supporting multilingual writers: undergraduate tutors must both take the tutor training course before they begin tutoring, and then once they are tutors, they participate in ongoing monthly training we call “professional development.” In the course section on multilingual writers, students watch Writing Across Borders and read DiPardo’s “Whispers of Coming and Going’: Lessons from Fannie” and Myer’s “Reassessing the ‘Proofreading Trap’: ESL Tutoring and Writing Instruction.”

However, this part of the class is brief–only 2 class periods. The IUWC tutors expressed that by the end of the class, they still feel nervous about working with multilingual writers. Most importantly, they shared with me that though the class helped, they felt unprepared for the realities of working with multilingual students, noting that while multilingual students feel empowered by having their dominant writing styles affirmed in a session, many multilingual writers still desire the tools to be able to effectively reproduce SAE (Standard Academic English) for success in their college courses and future career—something the tutors wanted to help them with, but weren’t sure how.

The Tension of Multilingual Support

Writing centers are excellent sites for supporting multilingual writers, positively impacting both writing skill and language acquisition (Patrick). Much of the literature from the last 20 years written for writing center administrators and tutors has taken a very practical stance, with strategies to follow in the session to help multilingual writers achieve greater fluency in their written academic English skills (Bruce and Rafoth, Praphan and Seong, Ryan and Zimmerelli). In recent years, however, the fields of composition, writing studies, and writing center studies have turned towards valuing and promoting linguistic justice, thanks to thought-provoking work by such scholars as April Baker-Bell and Aja Martinez. Numerous writing center scholars have championed the idea that linguistic justice—which affirms the value of students’ own languages—should be the goal of sessions, rather than helping students simply reproduce Standard Academic English (SAE), the dominant form of English that is taught and expected in American education, including at the university level.

As writing centers take up this perspective and see themselves as sites of affirming linguistic justice, what then becomes of students who genuinely desire and request assistance with developing SAE? This question is especially fraught given the underlying ethos of writing center work: that writers’ goals are primary and should be prioritized during the session. At the IUWC, multilingual writers often seek help with grammar and sentence structure—a request the IUWC tutors admit they fear, because they feel unsure of how to explain grammatical conventions and of the terminology and basis behind the rules that are second-nature to them.

To meet this need, I designed a semester-long professional development unit that addressed tutors’ requests for more training for working with multilingual writers— in a way that equips them with more pedagogical strategies while also affirming and valuing culturally and linguistically diverse ways of writing. This blog post shares information about this professional development unit, including its rationale, syllabus, lesson plan descriptions, and artifacts.

From Tension to Agency

The tension the IUWC tutors described mirrors Ruecker and Shapiro’s description of the struggle writing instructors face between affirming linguistic justice and helping multilingual writers gain fluency in SAE. Scholars who are “critical of the priority given to the teaching of standardized norms/conventions and have called on writing teachers to resist this privileging of standard norms” are what Ruecker and Shapiro call “idealists” (139). “Pragmatists,” on the other hand, are those who argue that we cannot withhold instruction in SAE fluency from students because in reality, students do need skills in writing SAE to be successful at college-level writing and instruction in such is expected by the students themselves. Ruecker and Shapiro suggest that the field should aim to navigate this tension with what they call “critical pragmatism”—or linguistic diversity’s middle ground between the opposing poles of aiming to assimilate and aiming to resist assimilation—which they believe can “help bridge the divide between idealist and pragmatist positions” (140).

Similarly to how critical pragmatism helps us to “pursue a ‘both/and’ approach to standard academic English—both teaching and problematizing the norms” (Ruecker and Shapiro 144), Shapiro et al. argued for the concept of “teaching for agency,” which promotes the empowerment of multilingual writers by recognizing “the resources that linguistically diverse students bring to our writing classrooms, but also takes into account these students’ needs and goals regarding English language development” (31). Shapiro et al. base their concept in the idea of rhetorical choice, or that “each linguistic, rhetorical, political, and institutional act is a choice that in turn shapes the language, writing, thoughts, beliefs, and actions of other people” (32). My professional development unit draws theoretically from both critical pragmatism and teaching for agency.

Professional Development Unit: The Details

The semester-long professional development unit that I designed encompassed three 2-hour training meetings. Tutors were asked in advance of each meeting to read a short piece of relevant scholarship. The readings were intentionally selected to not be the empirical pieces that our meeting activities were based on, but instead were works written by multilingual writers—in effort to amplify tutors’ understanding of linguistic justice. Each monthly meeting included a short lecture and an active learning component that helps the tutors put into practice the strategies they learned about. Provided here is an abbreviated version of the professional development syllabus that includes the readings (and can also be found below). Next, I will provide more detail on each training meeting.

Abbreviated-Professional-Development-Syllabus-Kerri-RinaldiMeeting #1

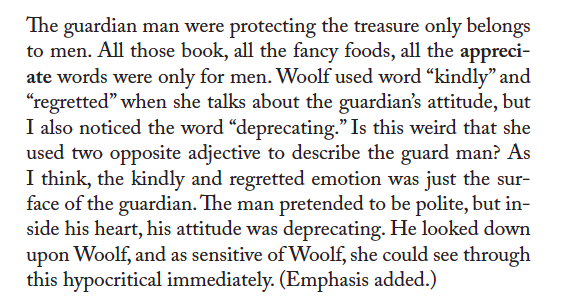

This month’s training was the entry point into this unit and also introduced the tutors to translingualism—an approach that sees linguistic diversity as generative and an opportunity for meaning-making, rather than as a roadblock to masterful writing. I began this meeting by inviting tutors to share their experiences working with multilingual writers and verbalize their desire for more training—what did they feel unsure about? What did they want to learn how to do? What did they struggle with? Next, we did a quick role playing exercise, where tutors paired off and were provided a short writing sample by a multilingual student, which originally appears in Gramm’s “Dialogic Openings for Recreating English.” Each pair had to spend 10 minutes role playing the tutor and tutee, and then switching. We then had a whole group discussion about what went well and what didn’t during the role play: What strategies did they use? Where did they feel tripped up?

Next, tutors were exposed to and practiced conversation and questioning that interrogates moments of translingualism to generate extended critical thinking and new means of expression. I defined translingualism and explained and then modeled Gramm’s translingual strategies: instead of correcting “errors” or making marginal comments (“this is unclear”) during a session, tutors can invite the writer to explain more fully what they mean by unclear phrases. This approach focuses on the unclear moment in the text as having creative potential rather than focusing on dissonance or inaccuracy of the deviation (Gramm 164). As a group, we discussed benefits of this approach: fostering confidence, creativity, and critical thinking. According to Gramm, “Students can use these innovations to articulate and advance thinking in their essays” (162). Tutors were also asked to reflect on their earlier role play session after learning about this strategy, and consider what changes they might make to their tutoring practices based on translingual approaches. Finally, I modeled using translingual strategies (modeling both potential questions to ask the writer and conversations that might follow) in practice on the whiteboard with the sample text used during the role play activity.

Meeting #2

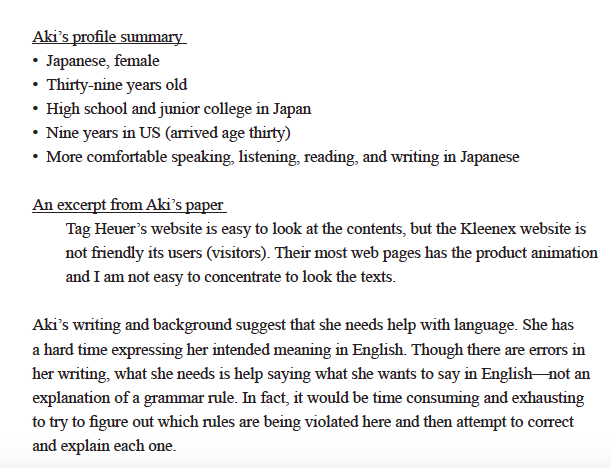

This month’s meeting focused on how both language acquisition and linguistic self-confidence can influence which in-session strategies might be more helpful for writers. I began this month’s training by describing and defining the concepts of eye learner vs. ear learner, as well as the relationship between language acquisition and the focus of the session. Next, we looked at Nakamaru’s generously provided tutor training materials, which includes two written case studies of multilingual students, including their bio and a writing sample (109-112). I asked tutors to share how they think they would approach a session with each writer/text, and what questions they would ask the writer, guiding them to use what multilingual writers share about their language acquisition and the strengths of their writing to determine whether their strategies should focus on global issues of meaning expression or sentence-level fluency.

Next, I gave a brief lecture on how writers’ linguistic self-confidence also impacts which motivational strategies are most effective in a session, as according to Patrick, and I then modeled several motivational strategies in action with my assistant director. Finally, I asked for volunteers to role play two different scenarios in front of the whole group: first, a session where the writer disclosed low self-confidence and then, high self-confidence in their writing, allowing the tutors to practice using or avoiding the strategies of praise, pumping, responding as a reader, empathy, and patience.

Meeting #3

This month’s focus was on allyship and grammar approaches. During the training meeting, we watched Scene 3: “Allyship at the Sentence Level,” a wonderful mock session provided by the Ohio University’s Graduate Writing & Research Center. We discussed what strategies we noticed the tutor using and in what ways they were effective. Next, we examined materials from Shapiro’s “Writing Consultant Workshop: Working with Multilingual (ESL) Students” together. We discussed Shapiro’s Grammar 101 Handout (6), and I asked tutors about the strategies suggested: did they already use any? Did any seem difficult to put into practice? Did they disagree with any of them? We also practiced on the whiteboard as a group revising and using meta-language to explain several examples from this handout, such as word form.

Shapiro-Workshop-excerptNext, we looked closely at the sample student writing provided in Shapiro’s materials (7) and reflected back holistically on the semester’s training, discussing which strategies we would use to approach this text. Finally, I wrapped up the training by defining and modeling Ben Rafoth’s three approaches to multilingual writers: assimilationist (helping the writer achieve flawless, nativelike writing), separatists (helping writer revise without regard for SAE), and accomodationist (letting the writer choose how nativelike they want their writing to sound; 97). We had a robust discussion surrounding which approach is morally and ethically “right,” and what we gain and what we lose by choosing each approach, which nicely wrapped up our unit by focusing on the nuances and complexities of transitioning from tension to agency with multilingual writers.

Conclusion

My aim for developing this professional development unit was to combine readings that affirm linguistic justice with practical strategies for working with multilingual writers that are rooted in translingual approaches so as to take up a critical pragmatist stance and promote writers’ agency. Equipping tutors with more pedagogical strategies that help students gain access to privileged forms of discourse while also affirming and valuing culturally and linguistically diverse ways of writing successfully led to the IUWC tutors feeling more confident and prepared to work with multilingual writers. By training tutors in this way, my hope is also that the multilingual writers who use our center feel supported and guided in their writerly journeys. I also hope that by sharing this training unit, that administrators who choose to use some or all of it for their own tutors will see similar positive outcomes as a result.

Works Cited

Baker-Bell, April. Linguistic justice: Black language, literacy, identity, and pedagogy. Routledge, 2020.

DiPardo, Anne. “”Whispers of coming and going”: Lessons from Fannie.” The Writing Center Journal 12.2 (1992): 125-144.

Gramm, Marylou. “Dialogic Openings for Recreating English.” Translingual Dispositions: Globalized Approaches To The Teaching Of Writing: 161.

Horner, Bruce, et al. “Language difference in writing: Toward a translingual approach.” College English 73.3 (2011): 303-321.

Martinez, Aja Y. “Alejandra writes a book: A critical race counterstory about writing, identity, and being Chicanx in the academy.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal (2016).

Myers, Sharon A. “Reassessing the” proofreading trap”: ESL tutoring and writing instruction.” Writing Center Journal 24.1 (2003): 8.

Nakamaru, Sarah. “Theory in/to practice: A tale of two multilingual writers: A case-study approach to tutor education.” The Writing Center Journal 30.2 (2010): 100-123.

Ortmeier-Hooper, Christina. The ELL writer: Moving beyond basics in the secondary classroom. Teachers College Press, 2013.

Patrick, Sarah. “Chinese International Students’ Reactions to Tutor Talk: Using Scaffolding Strategies to Support Language Acquisition in the Writing Center.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal (2020).

Phillips, Sacha-Rose. “Tutors’ Column:” Shared Identities, Diverse Needs”.” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship 42.9-10 (2018): 26-30.

Phillips, Talinn. “Allyship at the sentence level” . https://vimeo.com/gwrc

Rafoth, Ben. “Tutoring ESL papers online.” ESL writers: A guide for writing center tutors (2004): 94-104.

Ruecker, Todd, and Shawna Shapiro. “Critical pragmatism as a middle ground in discussions of linguistic diversity.” Reconciling Translingualism and Second Language Writing. Routledge, 2020. 139-149.

Simpson, Jollina, and Hugo Virrueta. “Writing Centers: The Musical.” The Peer Review 4.2 (2020): https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-4-2/writing-center-the-musical/

Shapiro, Shawna. Writing Consultant workshop: “Working with multilingual (ESL) students”.

https://sites.middlebury.edu/shapiro/files/2016/01/PWT_ESL_handout_F13.pdf Accesssed 18 Apr. 2023.

Shapiro, Shawna, et al. “Teaching for agency: From appreciating linguistic diversity to empowering student writers.” Composition Studies 44.1 (2016): 31-52.

Kerri Rinaldi is the Director of the Writing Center at Immaculata University, located outside of Philadelphia, PA. She is also currently a doctoral student of English at Old Dominion University. Her research interests lie in the intersection between composition practices and sociocultural identities, with a strong emphasis on disability.