By Samitha Senanayake

After completing an asynchronous feedback appointment and glancing, often with tired eyes, at the neat blocks of paragraphs in the global or summary comment, I feel good: job done! But it’s only recently that I’ve begun to wonder what the same paragraphs might make a student feel. Even before they read the text, what must feedback in the form of paragraphs feel like, sound like? In the same way, does a track change on Microsoft Word (the red lines that end in bubbles recording what was changed) immediately feel like the instructor is taking control?

Track changes are directive feedback. Though Writing Center scholarship recognizes that the “directive/non-directive paradigm” (Hedengren and Lockerd) for characterizing feedback may not always be helpful in indicating what kinds of feedback meet student needs, this scholarship often references tutors’ written comments as opposed to track changes which unequivocally edit a student’s draft. Even when addressing the question of multilingual writers who may request assistance with language learning, Kelvin Keown states that “[r]egardless of how one sees the role of a tutor, most practitioners agree that asynchronous feedback for [multilingual] writers should not simply entail the tutor editing or correcting the writer’s text (Rafoth, 2009; Hewett & Lynn, 2007; Myers, 2003).” While it is possible to think of not correcting the writer’s draft as a baseline for distinguishing writing center feedback from proofreading, it might nevertheless be interesting to think about contexts or degrees in which “corrections,” in the form of track changes, may help achieve the goals of learning and collaboration.

An important value that drives writing center pedagogy is dialogue, and one aspect of asynchronous feedback that tutors at times struggle with is the fact that we cannot often assess learning or build dialogue, because in the asynchronous mode the writer is absent and imagined. However, Dimitar Angelov and Lisa Ganobcsik-Williams point out that dialogue need not always look like a synchronous conversation, and that comments (track changes) placed side by side with the original text is dialogic because it makes visible “the semantic duality of the word” (59).

Angelov and Ganobcsik Williams, however, focus on one style of feedback: track changes and a summary comment. At the UW-Madison Writing Center, tutors use a different style, which consists of marginal comments alongside a global or summary comment, and track changes are not part of the officially recommended feedback template (which doesn’t necessarily mean they are discouraged). Since this style of feedback also has many affordances, I was curious to learn what writers would feel about track changes when presented with all of these different types of feedback and invited to compare.

Study Design

While working as the TA online Writing Center coordinator in Spring 2022, I collaborated with Lisa Marvel Johnson, teaching faculty at the Writing Center, on designing a focus group study to hear from some of the writers who request written feedback. One of the goals of the study was to understand how feedback style corresponded with student expectations; so, we established three styles for three rounds of feedback. After each round of feedback that Lisa and I provided, we had a focus group session to hear from our participants. The three feedback styles were as follows: 1) global comment (summary comment at the top of the draft) and marginal comments, 2) edits (track changes) and marginal comments, 3) only marginal comments. In our research design, we did not include a style with only track changes or edits because not asking questions or providing suggestions seemed to unsettle the basic definition of what constituted writing center feedback, which is why our second style of feedback, which most resembled “editing,” included marginal comments in addition to track changes.

Results

The Student Behind the Draft

The writers in our focus group consisted of three multilingual graduate students and one monolingual, advanced, non-traditional undergraduate student. In our conversations with our focus group, we learned that they, for the most part, appreciated track changes in combination with either marginal and/or global feedback. Our four participants helped us understand their personal learning styles and affective reactions to a given style of feedback, and the different contexts or stages of drafting in which a particular style of feedback would be helpful.

One of the participants that surprised Lisa and I the most was Jet (we asked participants to pick a pseudonym), the undergraduate student. Jet had a clear preference against the global comment. He told us that even though he knew we (the tutors) were trained to be gentle, he did not want to be treated with “kid gloves.” He wanted “aggressive feedback,” an affect he associated with track changes and marginal comments. Jet seemed to prefer directive instruction, straightforward and targeted, as opposed to the contextualizing language of the global comment, though he recognized that the latter might be helpful to other writers.

Jet said that he sometimes just didn’t have time to “ponder” writing and asked us to imagine what kind of feedback we would want if the assignment was due that night. He shared with us that he would return to the global comments later, but the marginal comments and track changes were helpful in a time crunch. Listening to Jet made me realize that unlike synchronous sessions, written feedback can be taken in piecemeal at different times. One way to be respectful of the pressures of deadlines that students write under might be to have a combination of different styles of feedback that the student can process in a way that works best for them.

Heimma, a multilingual graduate student, related to the global comment in a very different way than Jet; she strongly affirmed the global comment. She said that she often felt overwhelmed by large numbers of marginal comments and the global comment helped organize and manage the feedback. Heimma shared that having overlapping comments from track changes, where it was difficult to immediately trace the comment to the relevant location in the text, made the feedback difficult to read. I thought this seemed like a useful visual parameter for how much was too much! Heimma also identified a distinct affordance of track changes. She told us that seeing what the suggested change looked like sometimes made the instructor’s recommendation easier to grasp.

The Instructor Behind the Draft

We had set out to picture a little better the imagined writer, but in the process, we also encountered the imagined instructor. We realized that what track changes felt like could depend on the image the student had of the instructor! And if it was important for us to know who the student was, it was also important for the student to know where the instructor was coming from. Jet seemed to have his own picture of an instructor who showed an honesty and investment by unflinchingly intervening in the student’s draft, vs. an instructor who was more cautious and careful not to offend. Both Jet and Ely, a multilingual graduate student, seemed to feel that marginal notes, whether they were marginal comments or track changes, suggested that the instructor was conveying what they were “thinking” or how they were “reading” as they went through the draft.

There was also the image of the instructor as a general reader. After we had given the participants feedback with track changes, we asked them if an instructor could understand what they were trying to say well enough to make changes (as opposed to suggest changes) to their draft. Jet’s response was that “it’s not possible, but it’s not necessary that it be possible.” Echoing Angelov and Ganobcsik-Williams’s insight on dialogue, he explained that he wouldn’t have the chance to provide an explanation to his target reader; so, this readerly perspective was helpful.

Nevertheless, this image of a nondescript general reader also didn’t quite capture how the writers imagined tutors. They attributed certain qualities to us, and this shaped their perception of our feedback. They told us that they knew we were coming from a good place and that the advice was friendly. When we asked them how they knew we were friendly, they said our comments in the form of questions and suggestions had conveyed this impression, especially when they compared our comments to journal reviewers who simply said, “this makes no sense!” Conversely, participants also saw us as “experts,” from whom they were prepared to receive as many comments as time constraints allowed. While these participants were clearly capable of taking our track changes with a grain of salt, especially when it came to subject specific knowledge, it is possible that in some situations the perception of an instructor as an expert could make a track change harder to reject.

Our Study vs. an Actual Written Feedback Session

While we tried to faithfully mimic written feedback appointments, I do wonder if the context of this study influenced responses. For example, to further understand how our participants experienced track changes, we asked if this style of feedback felt disrespectful. Addressing a comment on Kabir’s draft (also a multilingual graduate student), Lisa shared that she felt she was being rude when she linked a Wikipedia article to signal a potential spelling error in a term on which Kabir was the expert. But Kabir said he had made this error before, and didn’t seem to experience Lisa’s brief editorial comment as rudeness. None of our participants seemed to experience our edits as disrespectful. And while this certainly challenged assumptions Lisa and I had about the potential rudeness of track changes, it is also possible that the particular context of our study may have influenced responses. If you know the person behind the track changes, it could make a considerable difference in how feedback is received.

Knowing his instructor may have also shaped Jet’s experience of track changes. When Jet talked about his preference for directive comments, he frequently brought up a Writing Center mentorship (a series of appointments across a semester, with the same instructor). In this context, he was able to request his instructor to follow a more directive style, and he found this feedback very helpful. This situation, however, is different from most asynchronous sessions where the student will not know the instructor and will not have had the chance to communicate with them beyond the intake form.

Concluding Thoughts: Finding Ways to Communicate

I had often heard written feedback tutors say, ‘if only we could hear more from students!” This study convinced Lisa and I that communication between instructor and student wasn’t simply a missing element that was necessary for learning and collaboration to happen in written feedback, but an added element that could enhance the unique affordances of written feedback. We also learned that students need to know a little bit more about us, not only who tutors are personally, but also our pedagogical approach. In this ideal situation, once students have a sense of who is behind the track changes, and recognize that requesting track changes will not be received as a request for an authoritative “cleaning-up” of their draft, track changes may prove to be a versatile addition to our asynchronous feedback toolbox. The challenge, of course, is to create this channel of communication asynchronously.

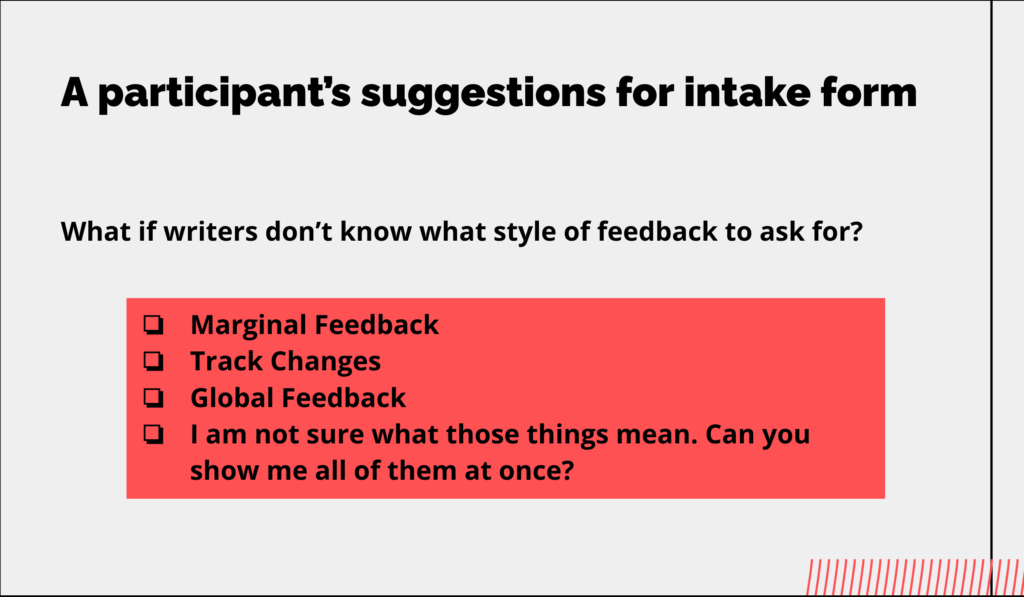

Facilitating this communication is a project that will most likely take more reflection, debate, and technology. But a potential starting point might be continuing to experiment with the intake form on WCOnline. When Lisa asked the group, ‘would student-writers know what kinds of feedback to ask for?’ on WCOnline, Jet had a wonderful idea! He suggested that in addition to potentially having boxes for each feedback style to tick on the form (a box each for marginal comments, edits and track changes, and global comment) we could also add a box that said, “I don’t know what these are, show me a bit of all of these.” Perhaps a student might tick that final box one day and set in motion a series of feedback that will lead to that appointment, where they pause, decide, and tick “track changes” and I don’t immediately assume that they just want their draft proofread.

References

Angelov, Dimitar, and Lisa Ganobcsik-Williams. “Singular Asynchronous Writing Tutorials: A Pedagogy of Text-Bound Dialogue.” Learning and Teaching Writing Online, Brill, 2015, pp. 46–64. brill.com, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004290846_005.

Hedengren, Mary, and Martin Lockerd. “Tell Me What You Really Think: Lessons from Negative Student Feedback.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 36, no. 1, 2017, pp. 131–45.

Keown, Kelvin. “A Big Cupboard: Developing a Tutor’s Manual of Model Asynchronous Feedback for Multilingual Writers.” Research in Online Literacy Education, vol. 2, no. 2, Jan. 2019, https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/tlc_pubs/1.

Samitha Senanayake is TA instructor at the Writing Center and a Ph.D. candidate in Literary Studies at UW-Madison. Her work is on modern anglophone literature and Buddhist thought in twentieth-century Sri Lanka with a focus on how secularism shapes criticism in the humanities.

As a teacher I found this article insightful. It’s quite interesting know how important written feedback is! I prefer student centred approach and often give them enough space to question and raise arguments.

Anyways, thanks for sharing. The article was helpful!

The comic strip is a clever way to illustrate the challenges of asynchronous feedback. It’s a reminder that even though the writer may not be present during the feedback process, it’s still important to strive for a sense of dialogue and collaboration.

As a teacher I found this article insightful. It’s quite interesting know how important written feedback is! I prefer student centred approach and often give them enough space to question and raise arguments.

Anyways, thanks for sharing. The article was helpful!

Having read the article, I, as a teacher, gained valuable insights into the significance of written feedback. It is fascinating to realize its importance! In my teaching practice, I adopt a student-centered approach and encourage my students to question and present their arguments. Nonetheless, I appreciate you sharing the article, and it was indeed helpful. Thank you!