By Anonymous

Authors’ Note: We are a collaborative of women graduate and undergraduate students of Color who work as peer writing tutors at university writing centers across a region on the East Coast and who anonymously present this collective counterstory. We are grateful for Dr. Talisha M. Haltiwanger Morrison and Talia O. Nanton’s (2019) “Dear Writing Centers: Black Women Speaking Silence into Language and Action” for inspiring our work.

Prologue

Video Transcript

As writing centers continue to espouse egalitarianism, develop critical praxes, and make strained (and now often forbidden) overtures to racial justice, telling the story of our work faces drastic shifts in university admissions processes, governmental attacks on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) frameworks; and privatization of university decision-making – all of which bring incredible employment precarity, severe budget cuts, and threats to learning and academic freedom. Also, the ChatGPT-ification of writing has compelled us to reconsider what it means to language and storytell anything at all. Institutional ethnographer and feminist scholar Dorothy Smith has explained that identity and consciousness process through the negotiation of power and social change, which can only occur in interaction and in concert across time and place among actual people whose variations of “complex personhood” (Tuck, 2009, p. 418) shape and are shaped by each interaction. A “self” amounts to an “ongoing concerting” (Smith, 1996, p. 181) of communication with other beings—human, non-human, artificial—through the to-ing and fro-ing of meaning-making sign-systems articulated with each keystroke, gesture, and utterance—each attempt to say and to be said to. I become intelligible to you, you become intelligible to me, and we become “we” through the stories we weave of our lives in conversation. What has been silent or silenced is heard, what has been misconstrued as illegible is rendered legible, and what has been unknown is translated with the desire for recognition and understanding. Our stories tell us into being; they tell us that we are not alone and that we can raise consciousness and empathy in one another, who were once, before the telling, strangers. Through stories in testimony, witness, poetry, image, and song, we change and are changed beyond perceived boundaries of difference, discourse, distance, flesh, mortality, and faith. We are more than ourselves in time and so we echo one another, guess at what might come next, and imagine who we could be as professionals, as people, as being-making-beings. Palestinian poet Refaat Alareer, not long before being murdered by Israeli Occupation Forces in December 2023, wrote “If I must die, / you must live / to tell my story.” My story extends to you, the living, a language and a future I might nver arrive at but that still will call you from your own tongue and in your own voice. Dear writing center colleague, friend, my future self, whom I might not become, read me into being from some other place and another time as plural, collective, polyvocal. Read me like you would fly a kite we have made together somewhere and sometime urgently against an indefinite blue possibility. Read me with remembrance and hope.

Counterstories

Click on a link below to jump to a particular counterstory or read them in the order they appear.

- Standardized language, standardized practice

- In Translation, We Thrive: A Letter to the Translators of Academia

- The First Wound Was English

- Taught to Be Quiet, Born to Be Outspoken

- Enough Talking, It’s BEEN Time to Be About It

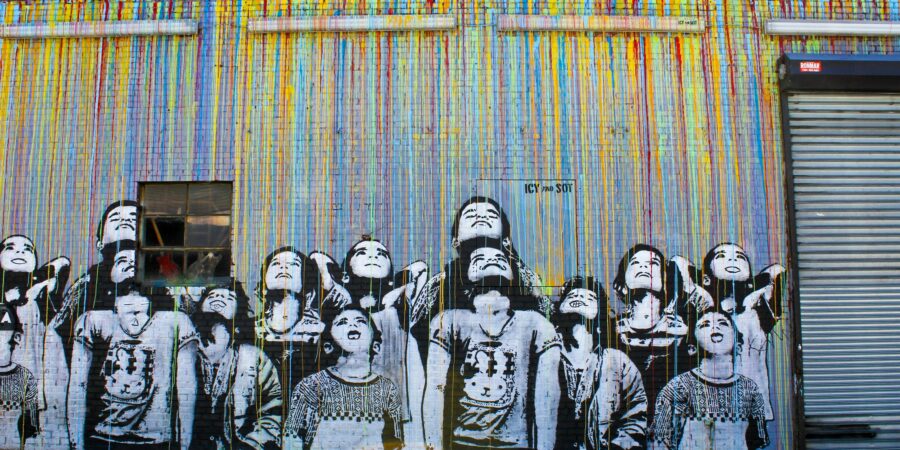

Standardized language, standardized practice

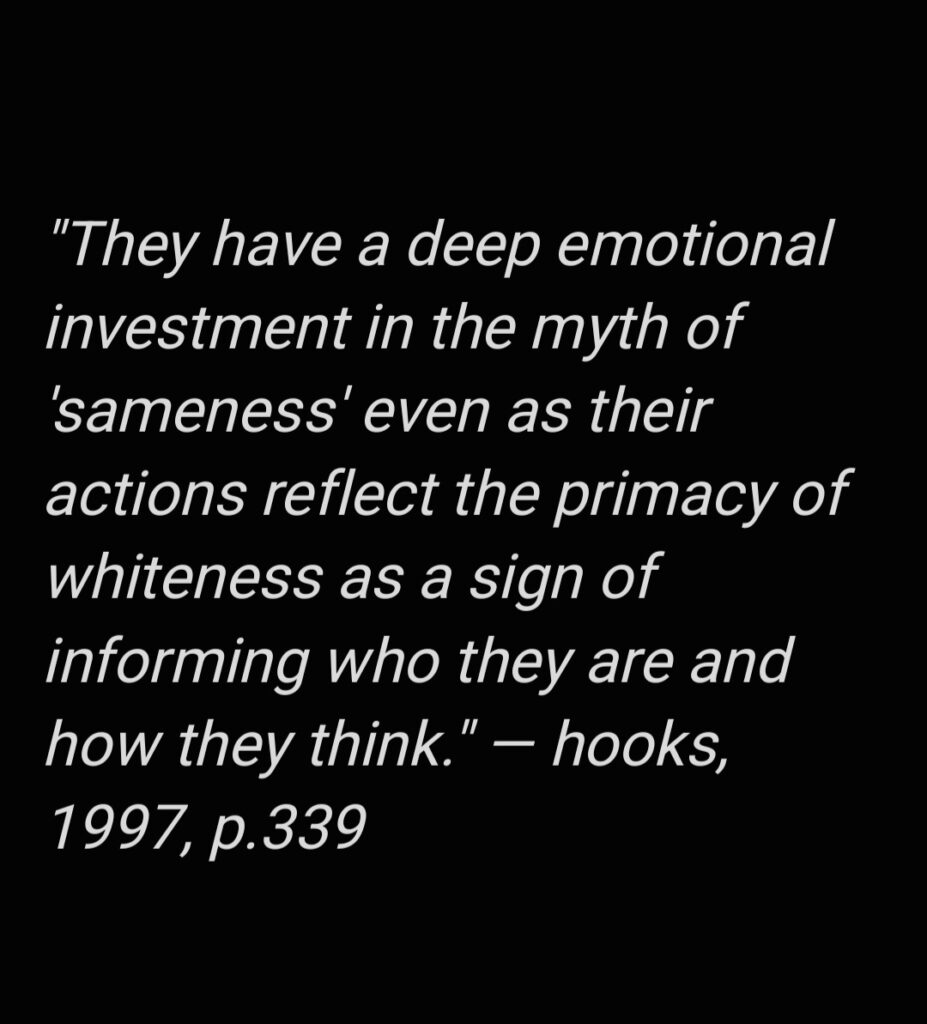

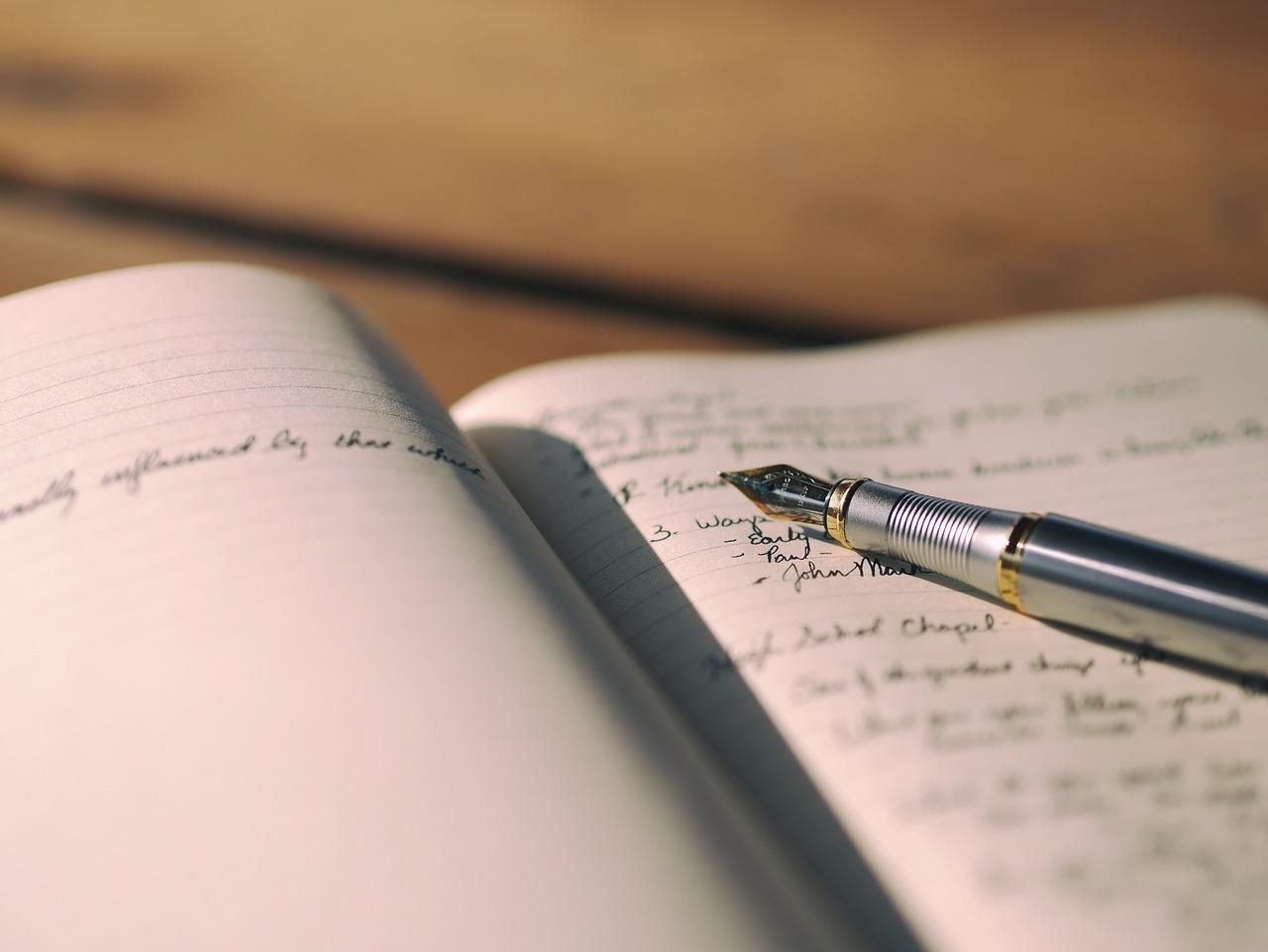

![A quote from writing scholar Alexandria Lockett: “The work of getting someone to talk and write ‘like educated (white) folks’ is an act of violence because it functions on the basis that patriarchal white supremacist manners of expression [are] superior to those of unassimilated non-white people” (2019, p. 27).](https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Image-1-Alexandria-Lockett-quote-image-935x1024.jpg)

Do you remember when you were a kid and the idea of going to college sounded like the most sophisticated milestone you could think of? Starstruck by the idea of being rewarded for learning through open acknowledgement of your contribution to English– because you always loved reading and writing, language was a toy and a tool and a comfort– sounded more glamorous than a cover of Vogue. Do the memories taste bittersweet to you too?

Be honest, do you regret it? Going to grad school, I mean. When I think about what people expect to hear when I enter the room, I can’t help but anticipate their disappointment, the “out of everyone that could be here, why is it you?” that I imagine echoes through their mind. Are you stronger than I am? Did the doubt go away?

Do your coworkers and cohorts still ask if you’re friends? It made me start to sweat when those familiar unfamiliar faces smiled at me like they knew something about me I didn’t. Did they ever make an effort to get to know you? Have they asked about your hobbies, taken an interest in your research, and meant it? Lip service, lip service, lip service. That’s what it seems like to me. Future me, prove me wrong.

Do they ask if you’re a team player? When someone wants coffee and asks if you’d like some, your preference makes a statement. I never managed to make the right choice. The taste wasn’t for me, and it never sat right. Twisting and turning– I thought my stomach was going to implode. Did you decide whether you wanted to belong?

Do you understand, now, what it truly means to assimilate into whiteness?

When people walk in and expect you to immediately take notice of their presence, do you greet them without thinking? Are you responding to those off-hours messages as soon as you get them? Do you take on that extra work, swallowing the sour, condescending entitlement of a person who isn’t making a request, they’re issuing a command. Do you bury that disapproval?

Are you making coffee you don’t even drink? Do you avoid getting strange looks when you don’t use that voice that sounds like them, that slightly higher-pitch with language they don’t find “urban” or “ghetto” so they don’t try to treat you differently. When you know they already don’t like you, do you pretend you understand why? Do you nod your head and turn away?

Future me, I hope from the bottom of my heart the answer is no, no, always no.

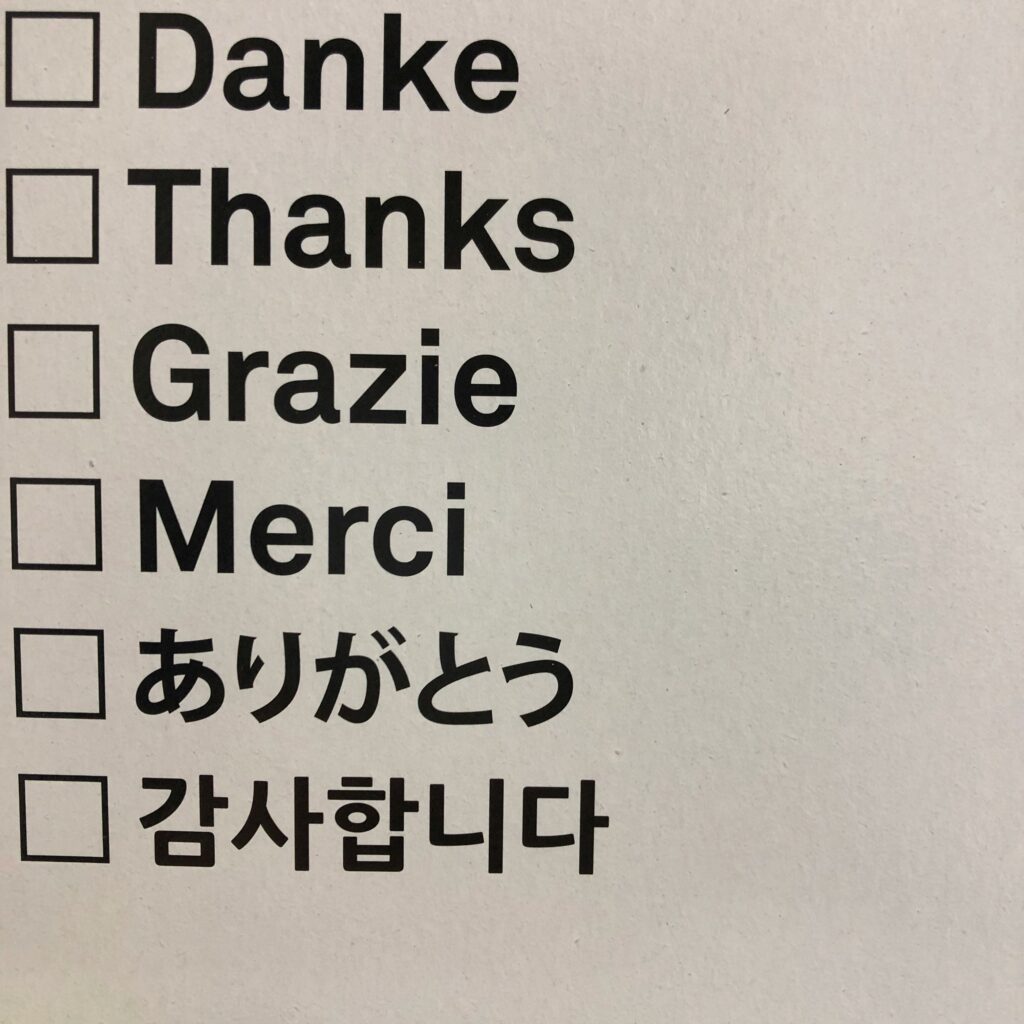

In Translation, We Thrive: A Letter to the Translators of Academia

You are not just studying here-you are living a translation.

Every day, you cross borders: linguistic, cultural, institutional.

And still-you show up. You listen, you guide, you hold space for others’ voices, even when your own feels like it’s still learning how to speak in this place.

But hear this:

Your English is not broken. Your language is not lacking.

Your voice is layered, rich with memory and meaning.

You come from systems of knowledge that have existed long before these walls.

As a graduate tutor and an international student, you hold dual roles-learner and teacher, guest and guide.

And sometimes, it’s lonely.

You navigate unspoken rules, unsure if asking questions will make you seem lost or bold.

You wonder if you’re being “too much” or “too foreign” or not confident enough.

But the truth is:

Your presence in the writing center is not accidental. It is transformational.

You are proof that literacy does not begin or end with Western norms.

That writing is not one tone, one grammar, one style-it is multiplicity, shaped by the world.

You’ve seen writers light up when you affirm their bilingual identities.

You’ve challenged the idea that a “strong thesis” is only one kind of sentence.

You’ve invited reflection instead of correction. And that matters.

So when doubt creeps in, remember:

You don’t have to erase parts of yourself to be effective.

You don’t have to “sound American” to be respected.

You are already enough.

You’re not here to fit in-you’re here to open doors.

To ask different questions.

To make space for stories like yours, and voices like yours, and futures wider than this institution imagines.

This is not just about surviving grad school.

It’s about helping build a future where all kinds of English, and all kinds of scholars, are seen as legitimate.

So take up space.

Speak slowly if you need to. Speak fiercely when you must.

Your story, your mind, your labor they belong here.

The First Wound Was English

Do you remember that article we read for class? Brown et al.’s piece on how African American Vernacular English is represented in ethnography? It stayed with you. The way it showed that even writing “this” as “dis”, or “brother” as “bruvah”, wasn’t just about spelling, it was all about the internal dialogue. It was about whose voice gets heard, and whose voice gets distorted.

You kept turning over one sentence: Are we representing a language, or reinforcing a stereotype? That question didn’t stay on the page; instead, it followed me into the classroom.

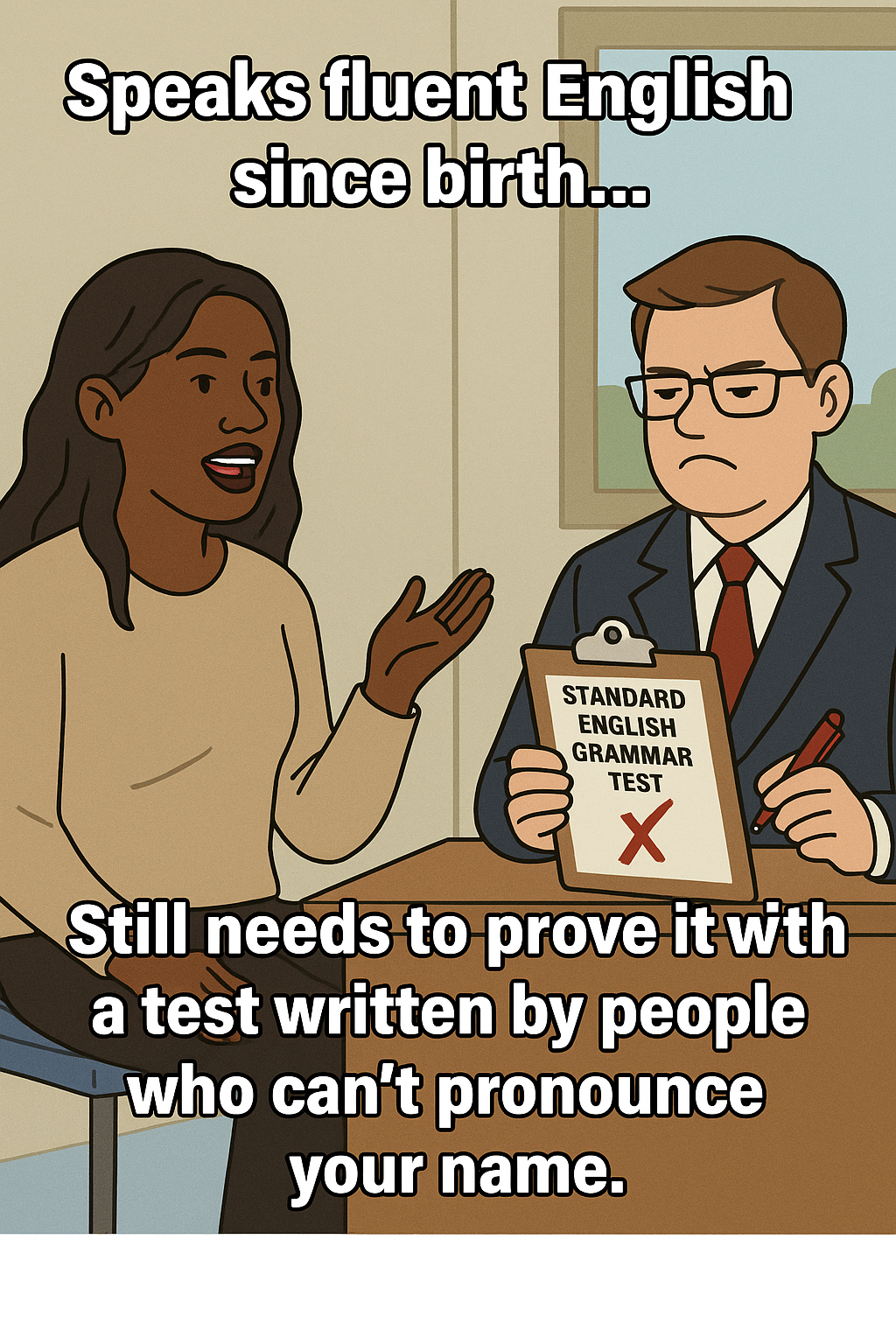

Do you remember the first time you took the TOEFL? How you studied not to learn English, you’d been taught in English your whole life, but to prove that you knew English. The “standard” grammar rules are the ones that are held on the application forms. Self, you weren’t learning language; you were learning how to be allowed in.

English had already become the first wound, they say: clearer, more professional, more academic. They mean: less you.

You saw it, especially in the first year, with your classmates silenced by fear of their accents; they had to rehearse every word before speaking. They began editing themselves before they were even spoken to in a softer tone, anything not to sound “different”.

It was about shifting standards, which is also echoed in syllabi, in very strict citation rules, even in the classrooms where theory only spoke at you and not with you. Even in our communities, ‘Black African Diaspora’, you are constantly reminded that your English needs to sound different now that you’re in America.

So you code-switched, you slowly lost your own identity, and you started to believe that you were the problem, but you’re not. We are not broken, and our English is not broken; what is broken is the demand to shift standards and rules of English.

The writing center was supposed to be a refuge, a place to “meet students where they are.” But where were you, Self? Sitting across from students, correcting their work according to the rules, you smiled, but deep inside, you were torn.

Should you ask them to change it? What I wanted to say: your voice is enough, write what feels comfortable for you, and don’t lose yourself.

That is the mirror that you used to help you understand more about academic writing, and the writing center became a border zone, a mirror of the university: Welcome, but only if you assimilate.

But what if we made spaces for Englishes? Let’s question who decides what’s “correct.” I have learnt that Language justice isn’t a luxury. It’s survival. We deserve to belong.

Taught to Be Quiet, Born to Be Outspoken

LISTEN [listen].1 We’ve come such a long way with our identity, do you understand that? Do you remember how timid we used to be when speaking up and vocalizing our thoughts as a young girl? Do you remember the criticism we received for speaking “proper English” instead of Ebonics as a black child growing up in the suburbs? I bet you remember how heartbreaking it was to lose the opportunity to learn our cultural dialect through our family. I realize that those moments don’t equate to the accomplishments we’ve achieved now, as a scholar, a tutor, and even an educated woman.

Using our voice and being outspoken was a quality that we struggled to accept and admire throughout our childhood; to this day, I’m still not sure why the backlash we received was so extensive. Yet as we grew up, activating that inner voice within us with so much passion was so influential. Our family, friends, and even society told us that our voice and our intelligence were a threat to the systems built out of fear and control. Yet, did you ever question why they wanted to silence you? Did you ever think about how different life would be if we didn’t search for the answers we wanted a long time ago? You should be proud of our perseverance through all the challenges, uncertainty, and confusion. Why are you not satisfied? It’s a trait we’ll never trade for anything material in this life.

Can you believe that you won an award for expressing how you feel, what you want to accomplish as an adult, and how you changed your inner self? Isn’t that so wild? I’m not surprised that we achieved our goals; I’m surprised to see how this life of ours has made us brilliant and impactful. You used to worry heavily about how people perceive you outside of those surface-level interactions. They don’t matter anymore. Why did we worry about people who were in doubt of our skills and who we were: they were never going to accept how talented we were. I know in the past you wanted their approval, attention, and validation – but you are worth so much more than a simple “GOOD JOB” [good job], a B on a report card, and a lousy comment from a teacher who didn’t value your work ethic.

Acknowledge that we will be recognized in this life one way or another, yet don’t forget how far we’ve come to find ourselves and release those burdens that weigh down on us. Use your voice, and remember that you can never impress someone more than you can impress yourself. You can be your own support system and make yourself feel loved 10 times more than anyone else. Those opportunities that we lost as a kid don’t matter now that we’re gaining what we truly want – a sense of self. The blessing to say “I know who I am” or “I’m proud of who I am, what I’ve done, and all that I’ve learned”. That’s something that not everyone around you can agree on and confirm within themselves, but you have the power to comfort yourself. Never forget that.

Audio Transcript

0:00-0:04 Look what I’ve found, come get down, it’s that revolution sound

0:04-0:07 Call it second emancipation, break these chains and let me out

0:07-0:10 It’s not violence I’m on about, but riot boots still hit the ground

0:10-0:13 Lower the gun, put down the whip, take a step back, hear me out

0:13-0:16 I am fanatic, employ guerilla tactics

0:16-0:19 Open up this lyrical automatic and put holes in your rhetoric

0:19-0:23 It’s archaic, kind of chaotic, almost barbic

0:23-0:25 But yet you stand and you swear by it

0:25-0:29 And I’ve been readily, steadily waiting for a chance to resist

Enough Talking, It’s BEEN [been] Time to Be About It

A wise woman once posed the question: do you know what it means to assimilate into whiteness? You have encountered the pressure to assimilate, but you didn’t quite have the language to describe what you were noticing. You won’t continue to lack the language. You never really had the desire to assimilate, but it didn’t stop those unsolicited comments—comments which underscore the importance of linguistic justice in the first place (Conference on College Composition and Communication, 2020; Young, 2010).

You face less scrutiny for not assimilating.

People of minoritized identities don’t have the privilege (Martinez, 2020).

You’re grappling with the expectation for you to assimilate into whiteness, continuing to grapple with it. You have the words to describe what you have been noticing. How are you, or anyone for that matter, expected to assimilate when it is human nature for a person to be multiplicitous? Many of us are living translations, but we’re told that standardized English is the it language (Conference on College Composition and Communication, 2021; Young, 2010).

There is a lot of TALK [talk] in academia about dismantling white supremacy by the same faculty who revere translingualism in the scholarship they present at conferences but rush students out of their offices and into writing center spaces to be “fixed,” having the expectation for writing consultants and writing center administrators to assimilate them into whiteness without discussions about race (Lockett, 2019; Thompson, 2023).

There is a lot of TALK [talk] in academia about dismantling white supremacy by the very students impacted by it the most. These are the same students who, despite being translingual in their daily lives, have been led to believe they cannot operate in academia the same way. To have a chance at being successful in academia they are told that they must sacrifice themselves by first adopting a language that is less them.

You stand at a crossroad between undergraduate studies and graduate studies or, as you might think of it, ACADEMIA [academia] ACADEMIA [academia] and more ACADEMIA [academia]. You can’t expect institutions to hold your hand as you hold a mirror up to their faces and you can’t wait to stand up for linguistic justice until you’re on committees as either a tenured college professor or a writing center coordinator.

You have been supported to use your voice as a woman who presents as white–a presentation which affords you more protection (Finch, 2024; Martinez, 2020, pg. 17). Be a voice for your peers who never made it out of the hood when you had the privilege to. Don’t simply relish in the reality of multiplicity for yourself; make it happen for other people. You have begun to use your voice for those who couldn’t, who don’t know they can.

Audio Transcript

0:00-0:02 [Instrumental fading in]

0:02-0:05 We’re everywhere

0:05-0:10 [Instrumental]

0:10-0:12 No need to return

0:12-0:17 [Instrumental]

0:17-0:19 I’ll show you the way

0:19-0:29 [Instrumental fading out]

References

Brown, R., Davis, J., & Shipp, S. (2021). Listening to language: Representing African American Vernacular English in ethnographic research. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 20(3), 190–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2020.1845170

Conference on College Composition and Communication. (2020). This ain’t another statement! This is a DEMAND for Black linguistic justice!. https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/demand-for-black-linguistic-justice.

Conference on College Composition and Communication. (2021). CCCC statement on white language supremacy. https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/white-language-supremacy.

Finch, M. (2024). White Passing – Finch Project 2. Soundcloud. https://soundcloud.com/michael-finch-841522970/white-passing-finch-project-2.

Fire From The Gods. (2016). Excuse me. Narrative. Rise Records.

Ghost. (2018). Miasma. Prequelle. Loma Vista Recordings.

hooks, b. (1997). Displacing Whiteness: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822382270-006.

hooks, b. (1997). Representing whiteness in the Black imagination. In R. Frankenberg (Ed.), Displacing whiteness: Essays in social and cultural criticism (pp. 338–346). Duke University Press.

Kaba, M. (2021). We do this ’til we free us: Abolitionist organizing and transforming justice. Haymarket Books.

Lockett, A. (2019). Why I call it the academic ghetto: a critical examination of race, place, and writing centers. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 16(2). https://www.praxisuwc.com/162-lockett.

Martinez, A. J. (2020). A Case for Counterstory. Counterstory: The Rhetoric and Writing of Critical Race Theory. Conference on College Composition and Communication of the National Council of Teachers of English.

Martinez, A. Y. (2025). Counterstory: The rhetoric and writing of critical race theory. National Council of Teachers of English.

Mike Wizowski-Sulley (n.d.). Face Swap. https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/mike-Wazowski-sulley-face-swap.

RandoAhh. (2025). Joker meme, where did the original come from?. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/joker/comments/1joy0h6/joker_meme_where_did_the_original_panel_come_from/.

Rafaat, A. If I Must Die. (S. Antoon, Trans.). https://inthesetimes.com/article/refaat-alareer-israeli-occupation-palestine.

Smith, D. E. (1996). Telling the truth after postmodernism. Symbolic interaction, 19(3), 171-202.

Thompson, J. (2023). Assimilation in the center: Writing tutors, race, and the hidden curriculum of neutrality. Writing Center Journal, 40(2), 58–75.

Thompson, F. (2023). How to play the game: tutor’s complicated perspectives on practicing anti-racism. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 21(1). https://www.praxisuwc.com/211-thompson.

Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending damage: A letter to communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 409-427.

Young, V. A. (2010). Should Writers Use They Own English?. Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, 12(1), 110-117.

This piece is authored by a collective of graduate and undergraduate women of Color who serve as peer writing tutors at university writing centers along the East Coast. Drawing from shared lived experiences and intersecting identities, they explore language, race, and belonging in academic writing spaces. Choosing anonymity protects the contributors amid institutional power dynamics and affirms their collective voice against dominant narratives that marginalize linguistic and cultural expression.

- Editor’s note: Throughout this piece, there are instances of words written in all capital letters. Words in capital letters are a feature of Black Language. The word is repeated in brackets in lowercase letters for screen reader accessibility purposes. Screen readers tend to read words in all capital letters as individual letters, so instead of reading the text as “good job” it reads it as G-O-O-D J-O-B. The decision to include both the all caps text and the bracketed lower case text was made in conjunction with the editor and the authors. ↩︎