By Robert Zatryb, University of Connecticut

Insecurities of Multilingual Students

‘I’m so sorry, English is not my first language.’

Have you ever heard this sentence in your tutoring sessions? Have you read it among the information provided by the student writer ahead of the appointment? I certainly did, with a surprising regularity and always in a similar, apologetic wording.

To some tutors and administrators, this tone might go unnoticed and be trivialised, but it actually should be very striking. The writers are, in fact, apologising for their multilingualism. They are apologising for who they are and where they come from. Never in my life have I heard ‘Perdon, que español no es mi primer idioma’ or ‘Entschuldigen Sie, dass Deutsch nicht meine Muttersprache ist.’ This sentence seems to happen exclusively in English. Whereas it might be seemingly ok to speak any other language as a non-native speaker, in English it is clearly perceived as a deficit.

This is the aftermath of the native-speakerism, an ideology that defines native speakers as ‘owners’ of the language and names them as an ultimate ideal in language acquisition. Native-speakerism has been broadly criticised in the field of language education, but is still widespread in everyday life in the US. At this point, I think it is important to note that native English speakers are a minority among all English language users worldwide.

When multilinguals come to the writing centres and place an emphasis on the native vs. non-native dichotomy, many think that how they say things is more important than what they say. ‘Is the tense form correct?’ ‘Is the word choice ok?’ ‘Can you fix my grammar?’ These are the questions around which some of their tutoring sessions will revolve. Unfortunately, sometimes this fixation is the effect of their professors sending international students to the writing centre to ‘learn English’.

Needless to say, in the context of US academia, those students already passed English proficiency tests and can speak, read, and write in English. Of course, they are diverse in terms of proficiency, but their linguistic choices do and always will differ from their monolingual English-speaking peers. This should be seen rather as an enrichment than a deficit. It is what makes multilingual voices unique: the linguistic and cultural backgrounds that shape us and that we bring in.

I speak not only from the observations I have made working with multilinguals but also from my own experience. I was spared from very traumatic situations because in my home Department of Literatures, Cultures, and Languages, we exist in a kind of a bubble. We mostly teach, study, conduct research, and communicate not in English, but in other languages. Non-native speakers of English form a vast majority of both the graduate student body and the faculty. Nevertheless, in classes that were in English— especially those taken outside of my department — I sometimes doubted if I sounded as eloquent and smart as my American peers. Did my reflection papers really meet expectations of graduate writing quality? I wonder how many of my English-dominant colleagues worry this often and this much about how their fancy and sophisticated thoughts come across in another language.

Insecurities of Multilingual Educators

I’m so sorry, English is not my first language.

I never even formally studied English before coming to the US four years ago to pursue my PhD. From where I am now, I want to thank the Spice Girls, Madonna, and the late Whitney Houston for meaningful linguistic input that resulted in my language proficiency.

Jokes aside, I was pretty anxious when I first got assigned to teach a writing class in English about German literature. Before, I had only taught classes that were in German. Neither German nor English are my native languages. In fact, my proficiency in both is comparable with just a slight advantage on the German side. However, I felt much more comfortable teaching in a setting where everyone else in the classroom was a language learner at different stages of their multilingual journey. Standing in front of a class of mostly native speakers of English and pretending I could teach them how to write an academic paper in their own mother tongue was unsettling, and I felt like an imposter. I had feared that the students might perceive me as an incompetent instructor because of my Polish-flavoured RP accent, imperfect use of definite articles, syntax influenced by other languages, and weird-sounding lexical choices.

Luckily, my concerns were not valid. The class was a success, students were amazing and it turned out, writing skills and expertise are transferable from other languages. I was still able to provide students with meaningful feedback regarding the structure, clarity, and even stylistics of their writing. Teaching this course also made me get in touch for the first time with the UConn Writing Center.* When I found out that there was an opening for the Assistant Director position, I eagerly applied and was hired. Coming out of my home department’s international bubble was definitely a challenge, but also a wonderful learning experience.

Although I am not the only polyglot at the UConn Writing Center, I am the only international person there and also the only one for whom English is not their dominant language. This does not go unnoticed; I often get asked by writers where I come from, because they notice a non-American accent. Sometimes I am concerned that this can be a sign of putting my competencies as a writing tutor in doubt, but it mostly turns out to be writers’ innocent curiosity. Most of the writers who come to my sessions really appreciate my feedback and support.

The only pushback that I ever felt in my sessions was, interestingly, from international students. When they start our session by stating that they are non-native speakers of English, I will assure them it is ok and disclose myself as a fellow non-native speaker. It usually relaxes the atmosphere and leads to really fruitful conversations. In very few cases, however, I noticed that it was not what they expected in the UConn Writing Center. I was not who they expected to meet. In one case, I even saw one international writer the very next day, with the same, short piece of writing, meet another tutor. I want to believe they just kept working on the same assignment, but I have a vague feeling they rather wanted to check the grammar ‘issues’ with a native speaker of English.

Multilingualism in Action

I’m NOT sorry that English is not my first language.

I come from a culture where multilingualism is cherished and learning languages holds a very important place in the educational system. This is why I was surprised to find out that, in the US, multilingualism is swept under the rug, avoided and omitted in the professional context. A language skills section, something obligatory in every CV and resume outside of the US, is sometimes absent from the curricula vitae of faculty members at US universities, even those faculty who work in departments that teach languages. The defaultness to a monolingual English-speaking setting is overwhelming. Multilingual abilities, on the other hand, are undervalued and underappreciated. Using languages other than English in public spaces is perceived as unprofessional. At the UConn Writing Center, we decided that it needed to change.

I have to thank my wonderful colleagues from the UConn Writing Center for having started the work on sensitisation to multilinguals’ struggles in academic context long before I joined the team. When I first got here, we already had a linguistic justice statement. Kudos to Kathleen Tonry, our former Associate Director, and fellow GAs who developed the project Racism in the Margins, an antiracist pedagogical initiative that dealt with oppressive feedback that students get from professors for their writing. In this spirit, my colleagues Margaret Bugingo, Tom Deans, and I are planning a workshop with UConn faculty about working with multilingual students, where we will touch upon ethical and practical issues.

But since my background and expertise is primarily in World Language education, I wanted to add to this discourse from another perspective. When I was first asked to give a workshop to our staff about linguistic justice, I gave them a task to write a short, simple text. The only rule: it cannot be in English. As I expected, some of them, highly proficient in other languages, had absolutely no problem with it, some struggled a bit, some others could not even write one sentence. This abundance of different outcomes and struggles led to a fruitful discussion on what it actually means to write in a language that one did not grow up with.

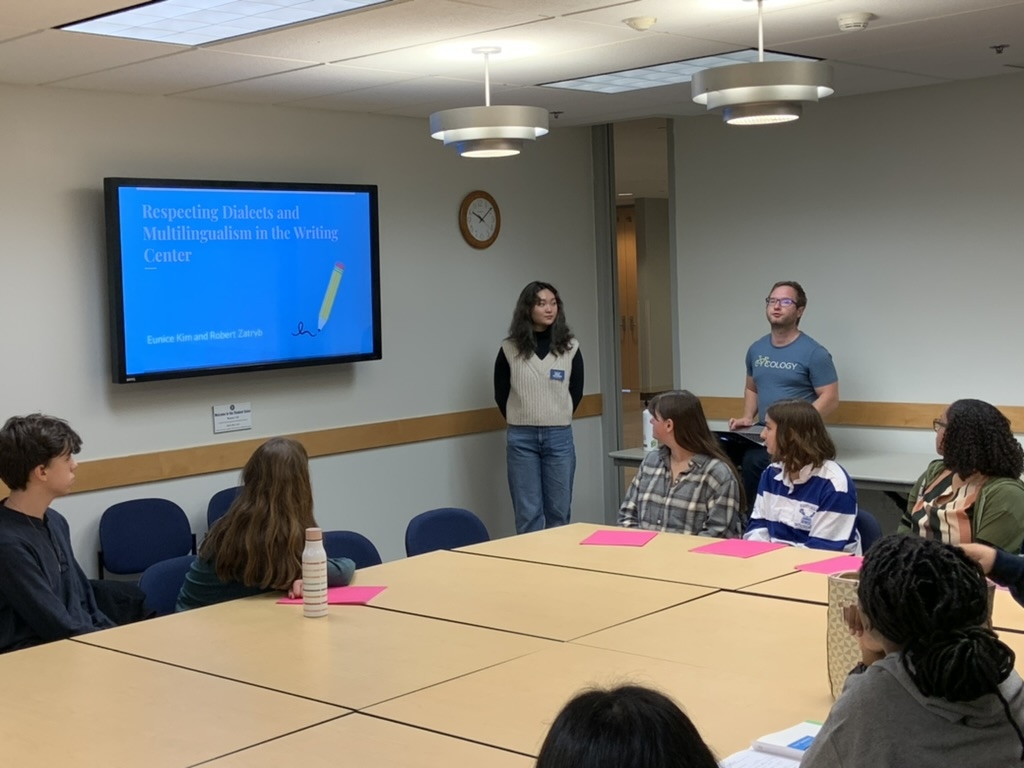

We continued this discussion on several occasions, both inside and outside of our staff meetings, where we shared our own experiences and those of our writers. We also read research about supporting multilingual students. Subsequently, we came up with tips on what (not) to do in our sessions. One of our excellent undergraduate tutors, Eunice Kim and I led a similar workshop at the annual conference for Connecticut’s high school writing centres.

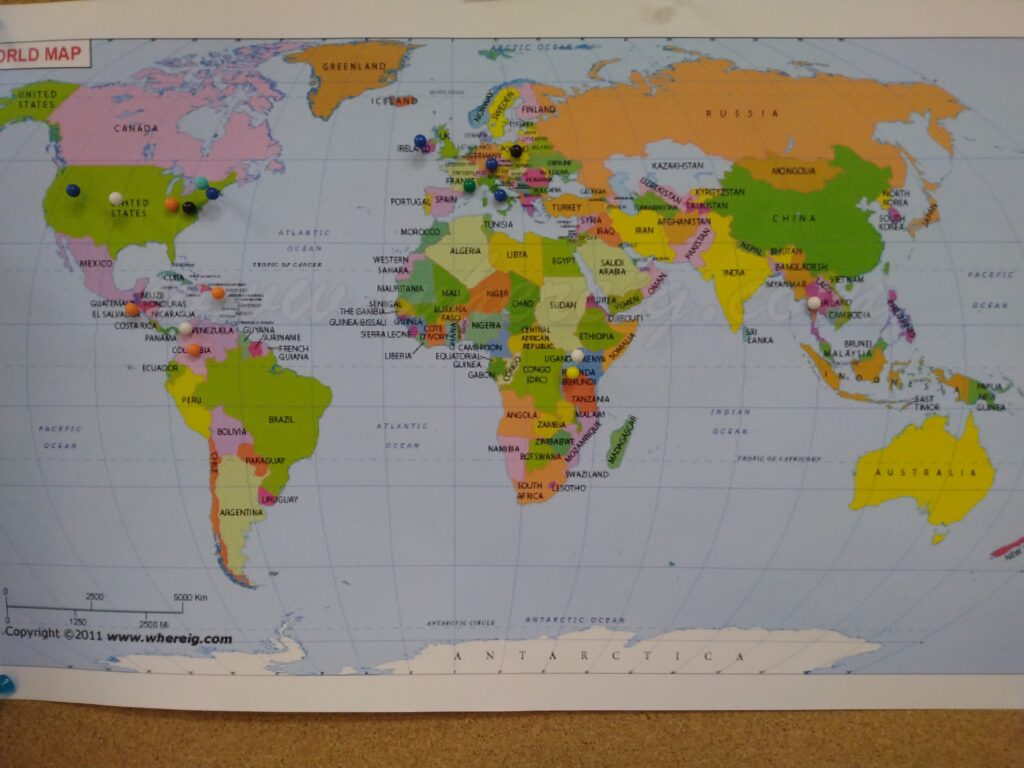

Another very important part of our work is making visible the linguistic and cultural diversity among the staff in our writing centre. My colleague Margaret Bugingo came up with an idea of a world map in space, where we mark all the countries that we have lived in. Margaret has also added language skills to the tutors’ bios on the web page. We try to actively use other languages to communicate with each other. You can enter the writing centre and from time to time hear both casual and professional conversations in Spanish, French, or other languages.

Our effort to embrace linguistic diversity led to a very heartwarming moment. I wrote an email in Spanish to Lizzette Irizarry, a tutor with whom I almost exclusively speak that language. For me, it was natural and logical; I would have felt awkward using a different language in written communication than we normally do. Lizzette, on the other hand, got excited about receiving a professional, work-related email in a language that she saw as a home language rather than a language for professional purposes. This anecdote shows how small, seemingly unimportant actions can have a big impact, open new horizons, and empower us.

Following the work of Noreen Lape on building up a multilingual writing centre, we are hosting tutoring sessions in other languages offered in cooperation with the Department of Literatures, Cultures, and Languages. This semester, we host graduate students who teach German, Italian, and Spanish. They offer writing sessions and conversations that will make it possible for each member of the UConn community to practise their language skills in a more informal setting than a classroom. I hope for this co-operation to be mutually beneficial. For the UConn Writing Center, we will expand our services and diversify our target group, and the programmes in World Languages will enhance the visibility of their work on campus.

I believe that all the actions that we have undertaken up to now are merely the beginning of a deeper work that needs to be done in the field. I am looking forward to continuing this work in the future. As they say in German, man lernt ja nie aus (one is never done learning). As the student and faculty populations at US universities become increasingly more multilingual and multicultural, this has to be reflected in the policies and practices of institutional settings, among these being writing centres. Questions of representation and visibility are central to the process of building an institutional space that is welcoming, inclusive and safe for all language users, of all languages.

*In this text, I use British spelling and grammar mechanics. However, since ‘UConn Writing Center’ is a ‘brand name’ of the institution I work at, I decided to use the American spelling when referring to it.

Thanks to Jackson Lyver for a tutoring session that helped me write this article.

Robert Zatryb obtained his MA in Applied Linguistics from the University of Warsaw (Poland). After having lived and worked in Poland, Colombia, and Germany, his interests in sociolinguistics and language pedagogy led him to pursue a Ph.D. in German Studies at the University of Connecticut, where he also serves as an Assistant Director at the Writing Center. In this role, Robert contributes to fostering linguistic justice and creating an inclusive and safe space for all language users. Robert speaks and teaches German, English, Spanish, Russian, and Polish. In his free time, he enjoys traveling and cycling.