By Kelle Alden, The University of Tennessee at Martin

Any university administrator will agree that accessible spaces are important, as they provide necessary services to disabled individuals and signify our commitment to equitable education. However, federal guidelines are complex, writing center staff are bound by political, financial, and practical constraints, and most people cannot imagine navigating their workspaces with a disability. As a result, writing centers are sometimes less accessible than they should be or could be.

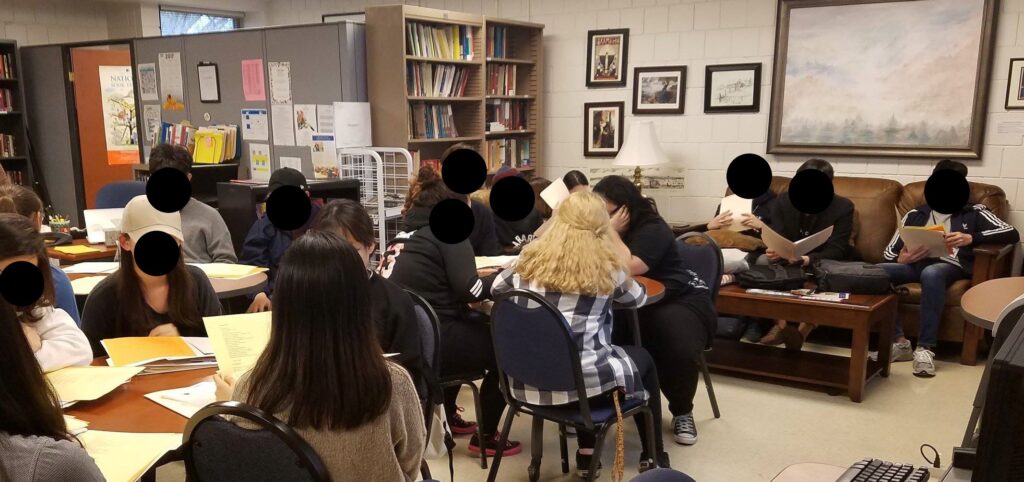

I began thinking about improving the UT Martin Writing Center’s accessibility shortly after joining as director in 2017, when I witnessed a senior English major shoving a table and chair out of his way to clear a path so he could navigate his wheelchair through the writing center. I had heard rumors that our writing center had tried unsuccessfully to hire this student as a tutor, and after observing and talking to the student about our space, I understood why he had refused employment with us. We needed to make changes quickly because several of our incoming freshmen would need wheelchair accommodations, but there were no university guidelines for me to follow as director. In addition, while recent writing center scholarship compellingly argues that writing centers should better understand disability (Babcock et al.), only a small percentage of total scholarship discusses physical disabilities (Babcock), and I found no resources describing the specific process of becoming physically accessible. Therefore, I studied the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Title III Regulations and applied them to a writing center setting. Having largely completed the process, I offer the following advice for writing center directors and other university administrators who wish to improve the physical accessibility of their spaces, particularly for students and employees who use wheelchairs.

Part One: Preparing a Space for Accessibility

Implementing physical accessibility guidelines often requires a certain amount of square footage. For example, pathways usually must be at least 36 inches wide so wheelchair users can navigate between tables and around furniture. Thus, when committing to ADA compliance, writing centers should start by maximizing the amount of physical space available. Doing so may require staff to closely examine the current items in the writing center as well as how the space is being used.

Remove All Unnecessary Equipment and Furniture

The longer a writing center remains in operation, the more clutter it accumulates. Some of these items have important cultural or sentimental value, but many of the items are out of use, outdated, or only present for aesthetic purposes. Many administrators might struggle with the idea of letting items go when funding for replacement items is rarely forthcoming. However, wheelchair users need enough room to move around, so any unnecessary clutter must leave.

Because I was a new administrator, I relied heavily on the staff when deciding what to keep. I asked them how long it had been since we used each of the items I was considering removing, and in almost every case, the staff were glad to see extraneous items go. By removing outdated books and obsolete equipment, we freed enough shelf and drawer space to remove several file cabinets and two bookshelves, increasing our open square footage significantly. We also eliminated a panel from a storage cubicle at the back of the writing center, expanding the tutoring space.

Consider Reducing the Number of Functions Your Writing Center Space Must Serve

The UT Martin Writing Center is housed in an 800 square foot classroom, but it contains an eight-computer lab with paid printing, a smart classroom projector and presentation equipment, a waiting area with couches, a walled-off cubicle that provides storage space, and a half-dozen tutoring tables. Many writing centers are built to be multifunctional: a tutoring and study environment one moment, an event space the next. However, the crowded and ever-shuffling collection of furniture presents logistical challenges and increases the chance that a wheelchair user will have trouble navigating the space. For us, multifunctionality was happening at the expense of basic functionality.

Working on this dilemma required some sacrifices: for example, the storage cubicle in the back of our writing center sometimes served as a private office for tutors who were working on administrative projects, but decreasing the square footage of the cubicle meant that it could no longer serve that function. We also acknowledged that we rarely give presentations in the writing center and stopped arranging the furniture to prioritize that. In the end, though, dropping these relatively small priorities improved our ability to focus on our most important tasks, and equally importantly, we were able to make room for wheelchair users.

Part Two: Determining Needs and Choosing Accessible Furniture

Reach Out to Your University for Funding

Securing ADA accommodations is often less expensive than institutions expect. According to research done by the Job Accommodation Network, out of 1,029 accommodations provided by employers, 56% cost nothing, and another 39% required a one-time purchase averaging $500 (Benefits and Costs of Accommodation). While even $500 can be too much to cover using a writing center’s annual budget, writing center administrators in the United States have considerable leverage when requesting additional funds from the university for accessibility purposes. (If your writing center is in another country, I recommend checking this United Nations list of disability laws to see what laws affect your location.) Although it should not be necessary to remind universities of their legal obligations, it may still be helpful to know the following:

- As the ADA National Network explains, unless an accommodation would fundamentally alter the nature of a program’s services, any public or private schools that receive federal funding must make their programs accessible by meeting the individual needs of each student with a disability (“What Are a”).

- Subpart E of Part 36 of the Americans With Disabilities Act states that any federally-funded university that fails to provide equal access to education is subject to enforcement measures, including private lawsuits, fines, and investigation by the ADA Attorney General (Americans with Disabilities Act Title III).

- According to the Office of Civil Rights (the agency that enforces anti-discrimination laws in any education programs that receive federal funds), discrimination complaints on the basis of disability can be filed by anyone, even if they are not the victim of the alleged discrimination (“How to File”).

- Finally, employees who are being discriminated against in the workplace or denied reasonable accommodation for disabilities can file a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which enforces federal laws against employment discrimination (“Your Legal Disability Rights”).

Writing centers can meet physical ADA guidelines without altering the nature of our practices, which means every federally supported university must provide the funds to do so. However, navigating each university’s bureaucratic structure to locate and claim those funds may still prove challenging. If the process for funding accessibility at your university isn’t immediately clear, reach out to your chain of command, the provost, any offices that address discrimination cases (like Title IX), and/or any program that manages equity concerns on campus. It may be possible to secure ADA equipment through grant funding, but compliance with federal law shouldn’t require external funding: the university is required to meet these standards, and schools should have money earmarked somewhere for this purpose. Find the person who has the authority to fund your ADA needs, and before finalizing your requests, work with students and staff to determine what your writing center should purchase.

ADA Guidelines for Wheelchair Accessibility

ADA guidelines are intimidating to read, and it’s up to administrators to determine which rules are relevant in a writing center setting. However, I recommend administrators focus on two major components of physical accessibility: providing appropriate work and study surfaces, and ensuring appropriate “paths of travel” in the writing center

Accessible Writing Surfaces

According to Section 902 of the updated 2010 ADA Standards for Accessibility, work surfaces (a category that includes writing surfaces) must fit within certain height, width, and depth parameters and be positioned so a wheelchair can make a clear forward approach (United States Department of Justice). The U.S. Access Board provides helpful illustrations for the ADA standards, which make them much easier to visualize (902.1-3).

Here is a simple list of legal requirements for an accessible writing center desk:

- There must be clear floor space in front of the work surface measuring at least 30 inches in width and 48 inches in depth (305.3).

- The desk or table must be between 28 and 34 inches in height (902.4.2).

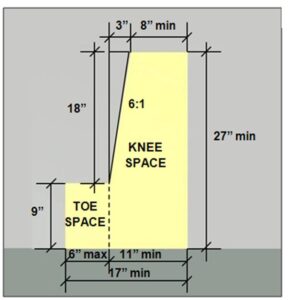

- There must be open space beneath the desk, and that space must measure at least 30 inches wide and between 17 and 25 inches deep. Some protrusions beneath the desk are acceptable as long as they don’t impede knee or toe clearance: see these U.S. Access Board diagrams for examples. (305.4)

These illustrations from the US Access Board show why knee and toe clearance is important for a person in a wheelchair. See ADA 305.4 here.

Accessible Paths of Travel

All paths of travel through the writing center must be at least 36 inches wide (4.3.3). However, when navigating turns around objects that are fewer than 48 inches wide, the minimum width of accessible paths increases, as shown in the diagram to the right.

Paths of travel also include entrances and exits, but the standards governing accessible entrances and exits are heavily dependent on what kinds of doors your writing center has. For example, ADA regulations may change depending on whether your writing center’s doorways are single vs. double-wide, sliding vs. swinging, or electronic vs. manual. The styles of entrances/exits determine what kind of hardware your doors should have as well as how much clear space needs to exist around the doorways. To find the correct rules for your situation, consult section 4.13 in the ADA Standards for Accessibility.

Accessibility is About More Than Compliance

As the International Writing Center Association’s position statement on disability and writing centers reminds us, physical accommodations should be “not merely legally acceptable, but thoughtfully, accommodatingly, and graciously accessible” (“Position Statement”). While the ADA guidelines are helpful, students and employees may benefit from additional considerations and accommodations beyond what is legally required. For example, ADA guidelines simply ask that workstation tables be between 28 and 34 inches in height (902.3), but some of our students sit taller in their wheelchairs than others, and they have varying degrees of upper body mobility and strength. One wheelchair user who benefits from additional considerations is UT Martin alumnus Aly Rusciano, who used our services for a year before joining our staff as a student tutor in Fall 2019.

While being interviewed about her experiences navigating a wheelchair at our university as a student and an employee, Aly listed accessible desks as one of the top three most important accommodations she received. However, even the ADA compliant desks the university purchased for our classrooms were often ill-suited for Aly. Because the ADA accommodations are written with a standard sized wheelchair in mind instead of Aly’s custom-fit power chair, she rode much higher in her seat than ADA anticipates, and her knees and toes bumped against the non-adjustable desks. Additionally, the basic adjustable desks use a crank that requires some strength and leverage to turn, and they are so heavy that two to three people are needed to lift them. Aly stated that even the imperfect desk solutions improved her educational experience considerably, but every wheelchair-using student’s mobility and measurements may be different, so providing roomier and easily adjustable desks is the best way to meet a variety of needs.

The first furniture upgrade I decided to make for the writing center was a single ADA-compliant table on which to place our accessible computer. I wanted to find a desk that could be raised and lowered for additional comfort, ideally without requiring much physical exertion. When searching for ADA equipment, I soon found that tables labeled “ADA-compliant” came with a significant markup despite meeting bare minimum standards. However, tables that met all the ADA requirements but were labeled as “standing, adjustable desks” were comparably priced, but with better features and better reviews. For example, when I was searching for tables, this ADA model table cost $361. To adjust the height, students have to bend and adjust two gears on either side of the table, which may or may not be feasible for them.

In comparison, I was able to purchase a stand up desk that adjusts electronically for $399 on sale. When I spoke to our wheelchair-using alumni, I learned that the standing adjustable desks were most similar to what they had purchased for themselves at home.

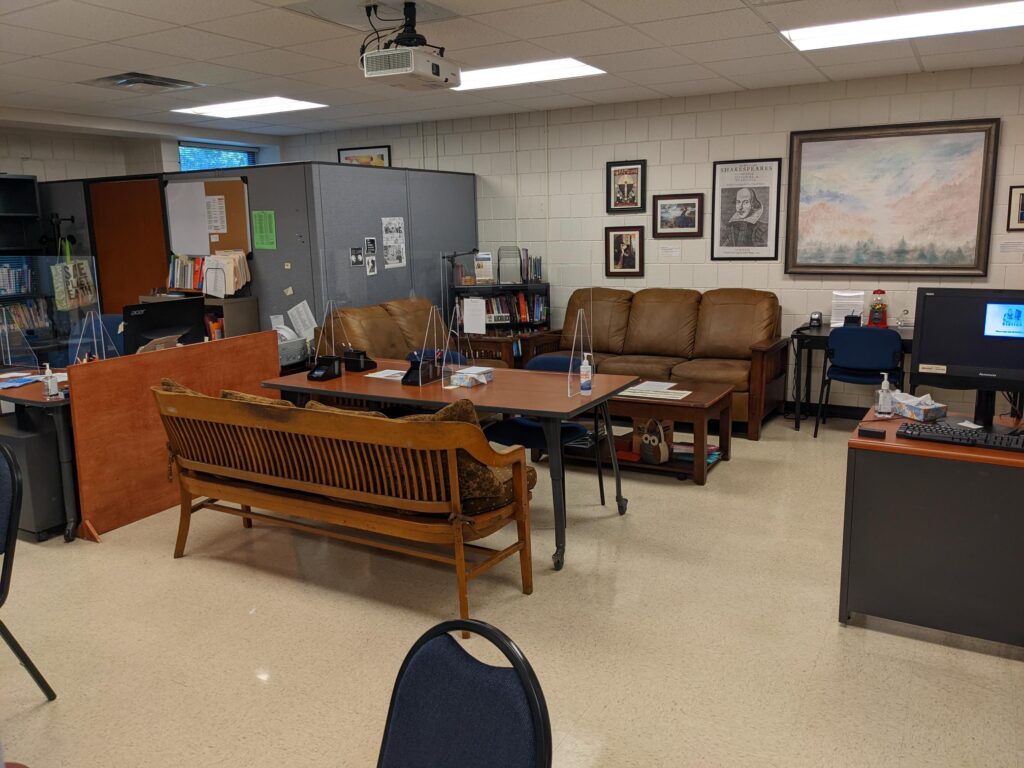

In most educational spaces, the majority of the furniture is not required to be ADA compliant: as long as one accessible space exists for students, the entire learning space is legal. However, full, thoughtful accommodation requires making as much of the space accessible as possible. When our writing center hired Aly as a student tutor, we needed to reconsider all the furniture in the writing center, especially the tutoring stations. The previous UTM writing center tutoring tables were oversized and kidney-shaped, and their designs were friendly and fun. However, the tables were also space-inefficient, and everyone on staff found them difficult to navigate around. It was also difficult to park wheelchairs at the tables.

The problem of being too multifunctional appeared again when our staff met to discuss our furniture needs. We dreamed up a long list of ideal functions: the perfect tables would be ergonomic and modular, stackable and light, equally suitable for ADA accommodation, conducting sessions, and hosting events. We never found the perfect furniture, so we chose ergonomic and modular over stackable and light. We knew we would have to rely on having staff on hand who could lift and rearrange tables on occasion, but we decided we could find people to assist if needed. Once again, we prioritized ADA accommodation and tutoring over presentations.

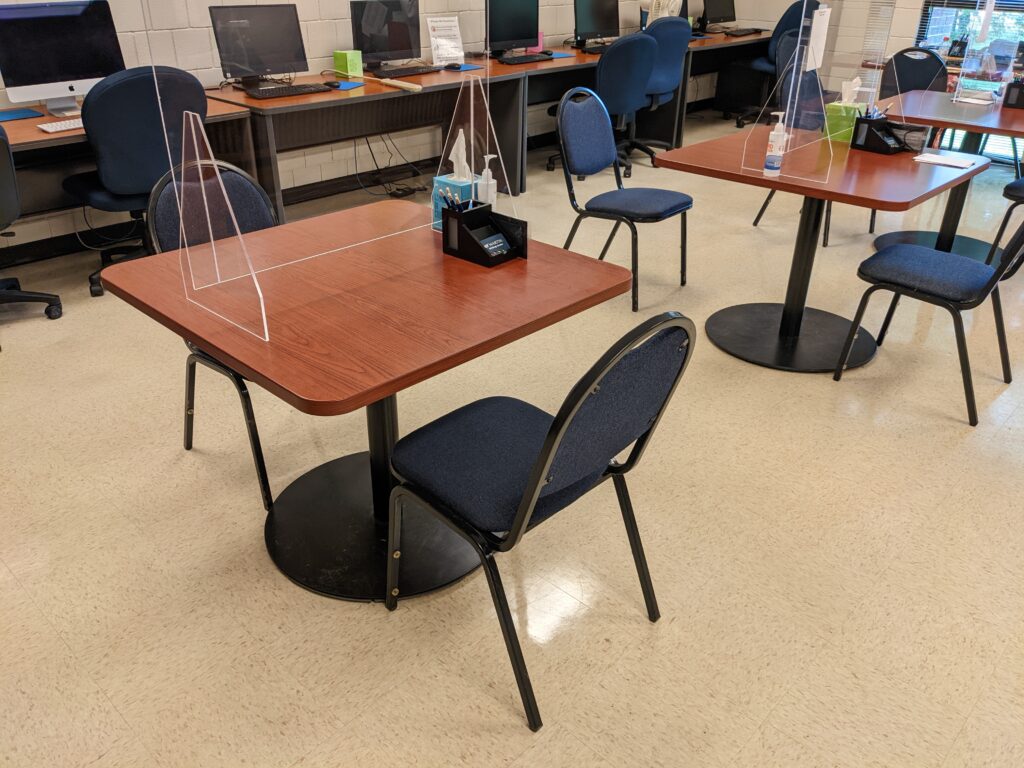

I presented some options to the staff, and we voted to replace all of our kidney tables with 36-inch square tables, featuring a center base and a pneumatic raise/lower function. The square shape was easier for wheelchair users to navigate around, and the center base made it much easier to tuck in chairs and park wheelchairs at each table. Aly started work three months after the tables arrived, and she noted that increasing the amount of ADA accessible furniture in the writing center improved her ability to use our space as both a student and tutor. When we only had one desk, Aly had no choice but to use it, which was awkward for her during busy times when people were blocking her path and she didn’t want to ask them to move. Making the majority of the furniture convenient removed the burden on Aly: “Once you got those tables, I was like, Sweet, I can sit anywhere. I can just roll up and adjust the table or ask for help adjusting the table.” Choosing the same accessible design for all the tutoring tables also had a positive emotional effect on Aly, as she explained: “When you guys got the tables, it wasn’t just because I was working there, it was for everyone. You guys aren’t changing something up to be like, ‘Oh, my goodness, you need so much help. I’m so sorry.’ It’s not a pity party, and it’s not, ‘This is such a hassle. I can’t believe this person is making us change all this.’ It’s something that’s inclusive and making someone feel like they’re still a part of the community.” Aly also enjoyed seeing everyone using and liking the new tables because it emphasized for her that accessible spaces don’t have to be conspicuous, and anyone can benefit from accessibly designed furniture.

Ask Students and Employees What They Need to Succeed

When designing a space, it is imperative to hear the perspectives of all the people who will use that space, including not only all the staff, but any visitors who might benefit from increased accessibility. Surveys can assist with this process, but I found that wheelchair-using students, faculty, and alumni were happy to provide direct feedback on my ideas when I requested it. Administrators might worry about how to best approach the subject of accommodation with disabled students and staff, but Aly shared some helpful tips on what kinds of conversations helped her the most.

Aly emphasized that the way tutors broach the subject of accommodation with our visitors matters. She recommends that tutors phrase questions the same way they would for a non-disabled person and avoid making assumptions about a person’s level of ability. For example, instead of automatically grabbing items for a student or asking invasive questions about what they can or cannot do, ask, “How can we make this space work best for you?” As Aly pointed out, “Everyone will answer that differently, no matter their ability, which is why it makes it the perfect question to ask because you’re not singling them out for being different. We’re not that different. We just have to do things a little differently.” Additionally, Aly recommends conveying to all visitors to the writing center that if there is anything in the space that we can help with or change, we are happy to do so.

In general, Aly suggested that customer-service oriented statements are a much better choice than questions that pry for details about a person’s disability because the implications of those questions can make a person with a disability feel like they are the problem rather than the space they are in. In contrast, keeping a casual attitude about accessibility requests and treating them like any other request helps students feel at ease in the space, as Aly notes: “Making it not a big deal is what, for me, makes such an impact. I think, Oh, cool, this is normal. There’s nothing different about needing this chair or cable moved.”

While seeking feedback from students with disabilities gave us an important perspective, the biggest reason for the UT Martin Writing Center’s improved accessibility is that the staff and student tutors committed to the process from the moment I introduced accessibility as a priority. At every stage, the staff contributed their ideas on how we could rearrange furniture and what purchases we should prioritize, and they have gone out of their way to keep the writing center accessible. The staff watch for “trouble spots” in the writing center and discuss ways to resolve the issues. They use marking tape to denote where the tables go so no piece of furniture drifts out of place, and they keep their backpacks and personal items off the floor and out of the way.

The Long-Term Commitment

Even now, the writing center is not what I would call perfectly accessible. A wheelchair user might still have to ask for assistance when retrieving books from a high shelf or fetching snacks from the storage area. We also faced new challenges during the global pandemic, and we rearranged our space again, this time focusing on crowd management, safety, and cleanliness. Although we have worked to make sure our new setup remains accessible, there is always a chance that new visitors and staff will need different accommodations that we have not yet thought to provide. Aly emphasized that preparing to encounter new needs is simply part of accessibility, stating, “It really all depends on the person coming in, so it’s hard to make something fully accessible when it’s all very individualized.” Accessibility is therefore not just a legal benchmark, but an ongoing commitment that requires consistent communication with staff and students and the willingness to adapt our space for each new person who seeks assistance with writing.

Works Cited

Americans with Disabilities Act Title III Regulations Part 36: Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Disability in Public Accommodations and Commercial Facilities. ADA.gov, 17 Jan. 2017, https://www.ada.gov/regs2010/titleIII_2010/titleIII_2010_regulations.htm#subparte.

Babcock, Rebecca. “Disabilities in the Writing Center.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, 2015, http://www.praxisuwc.com/babcock-131.

—. Writing Centers and Disability. Fountainhead Press, 2017.

Benefits and Costs of Accommodation. Job Accommodation Network, 21 Oct. 2020, https://askjan.org/topics/costs.cfm.

Guide to the ADA Accessibility Standards. U.S. Access Board, https://www.access-board.gov/ada/guides/chapter-3-clear-floor-or-ground-space-and-turning-space/#.

Position Statement on Disability and Writing Centers. International Writing Centers Association, 2006, https://writingcenters.org/position-statements/.

Rusciano, Alyssa. In Person Via Zoom, 29 Jan. 2022.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Disability Laws and Acts by Country/Area. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/disability-laws-and-acts-by-country-area.html. Accessed 26 Jan. 2022.

United States Department of Justice. 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design. 15 Sept. 2010, https://www.ada.gov/regs2010/2010ADAStandards/2010ADAStandards.pdf.

What Are a Public or Private College-University’s Responsibilities to Students with Disabilities? ADA National Network, Jan. 2022, https://adata.org/faq/what-are-public-or-private-college-universitys-responsibilities-students-disabilities.

“Your Legal Disability Rights.” usa.gov, 27 Oct. 2021, https://www.usa.gov/disability-rights.

Dr. Kelle Alden is an Assistant Professor of English and the Director of the Writing Center at UT Martin. Feel free to reach out to her at kalden@utm.edu with questions, comments, or rants about ADA guidelines.