Dear Future Writing Tutor

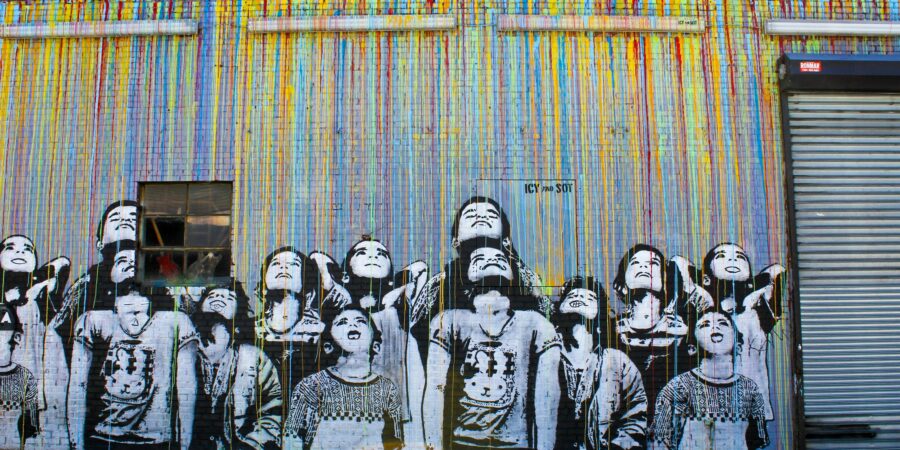

By Anonymous—Do you remember when you were a kid and the idea of going to college sounded like the most sophisticated milestone you could think of? Starstruck by the idea of being rewarded for learning through open acknowledgement of your contribution to English– because you always loved reading and writing, language was a toy and a tool and a comfort– sounded more glamorous than a cover of Vogue. Do the memories taste bittersweet to you too? […]